Woodvale Cemetery in Brighton is a Victorian-era sanctuary where the famous, forgotten, and controversial have found their final resting place, writes guest writer MAX CHAMBERLAIN

The black iron gates of Woodvale Cemetery separate the takeaways and barber shops of Lewes Road from a hidden gem of Victorian funerary art.

The noise and bustle of the flamboyant city of Brighton gives way to picturesque landscaped grounds and the stories of those whose journey has ended there.

A brief history of Woodvale Cemetery

Brighton began its life as a humble Saxon fishing village, growing amidst the remains of prehistoric camps, forts and barrows.

When 18th century physician Dr Richard Russell extoled the medicinal value of its seawaters, the town found a new life as a fashionable destination.

The Prince Regent cemented its status when he built the ostentatiously oriental Royal Pavilion in the town centre. The fashionable folk of the Regency period flocked to enjoy Brighton’s many attractions and distractions.

However, new life brought new death and, by the early 19th century, Brighton’s churchyards could no longer accommodate the town’s growing population.

Concerns about the toxic miasmas rising from decomposing bodies forced the council to seek new provision for Brighton’s burials, far from the town centre.

The 20 acres of land for the new cemetery was generously donated by the Marquess of Bristol and Brighton’s new burial grounds opened in 1857.

The impressive new cemetery was landscaped by Mr W. Wheeler of London, blending the grandeur of high Victorian Gothic-revival style with more prosaic Sussex flint.

Cemeteries like Woodvale were more than just burial grounds.

The Victorians lived in an age when life was fragile.

With disease all around and limited means by which to avoid or treat it, they were obliged to face the stark reality of their own mortality.

They did this by ritualising death, perfecting the art of dying.

Cemeteries were Arcadian gardens where they could commune with their loved ones. Winding paths lined with conical evergreens led to quiet spaces and beautiful vistas.

Tombs displayed iconography alluding to a life well-lived, the nobility of a good death and a hope for the afterlife.

These garden cemeteries were built to be a pleasant destination, a way to cement one’s status in death as in life and a source of civic pride.

In 1930, the cemetery marked a new milestone in its progression.

The twin, mortuary chapels were converted to accommodate the first crematorium in Sussex.

The archway through which horse-drawn hearses used to pass was blocked off and lined with memorial tablets.

The Parochial Cemetery was given its current name of Woodvale Cemetery in 1955.

Some notable burials at Woodvale

Woodvale became the final resting place for Brighton’s diverse population.

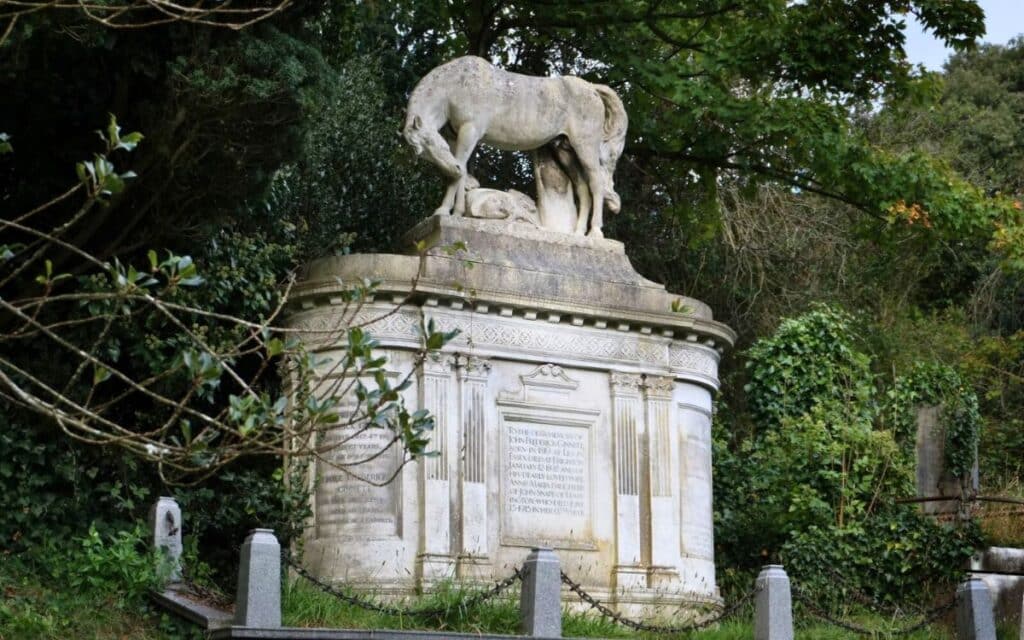

There is the horse-topped tomb of circus proprietor John Frederick Ginnett, the son of a French cavalryman who had used his equestrian expertise to found a circus of performing animals.

Circus Ginnett exists to this day. Another tomb is of Thomas Malcolm Sabine Highflyer, a boy from East Africa who was rescued from a slave ship off the coast of Zanzibar at the age of eight.

He was brought back to Brighton where he was housed and educated, tragically dying from consumption at 12 years of age.

A more recent visitor was Dame Vera Lynn, who was cremated at Woodvale in 2020.

Her funeral procession was marked by a spitfire flyover and a spontaneous rendition of “We’ll Meet Again” from the crowds who had gathered to see her on her way.

The funeral of Aleister Crowley

Another notable post mortem visitor to the cemetery was the most famous, and infamous, occultist of the 20th century: Aleister Crowley.

Crowley was an uncompromising iconoclast who delighted in the mythos that grew up around him as ‘The Wickedest Man in the World’.

Towards the end of his life, Crowley had fallen foul of his own hubris.

He had squandered his inheritance, been banished from several countries and was bankrupted by a failed libel case.

He died of bronchitis in a bohemian boarding house in Hastings on 5 December 1947, at the age of 72 years.

Following his death, Hastings council refused his wish to be buried in the town, perhaps fearing the prurient interest his funeral would attract.

He was therefore shuffled down the coast to the more liberal town of Brighton for cremation at Woodvale Cemetery.

Contemporary press reports describe a raw winter afternoon, with leaves wet and muddy on the ground.

The 20 or so mourners gathered around Crowley’s blue-black embossed coffin formed an odd group.

There were serious-faced, elderly men, well-dressed women in lavish furs and assorted youths with outlandishly long hair.

The service was read by Crowley’s old friend Louis Wilkinson.

In keeping with his life, his death was dramatic.

Wilkinson read excerpts from Crowley’s Hymn to Pan, Gnostic Mass and Book of the Law in a powerful and resonant voice.

The ceremony culminated in a proclamation of Crowley’s entreaty to follow one’s spiritual destiny, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.”

As the coffin rolled towards the furnace, a young woman in a fur coat and incongruently bright silk headscarf rushed forwards to place pink carnations on the coffin lid.

In death, as in life, the Crowley myth machine rumbled on.

Following the ceremony, one of the long-haired young men warned the reporters gathered hungrily to seek scandal “Better be careful what you write – Crowley might strike at you.”

The doctor treating Crowley, William Brown Thomson, died the day after Crowley’s passing, fuelling rumours that Crowley had cursed him for refusing to prescribe more heroin.

A Brighton council meeting described the funeral as a “black magic ritual” and resolved that such an event should never again take place at the cemetery.

Crowley’s ashes did not remain at the cemetery but were sent to Karl Germer, Crowley’s appointed spiritual heir.

In his New Jersey garden, the ashes were either dashed against a tree by Germer’s wife, or respectfully buried in a wooden box, depending on which of Germer’s accounts you choose to believe.

A final resting place for all

Woodvale Cemetery, with its grand Victorian architecture and serene landscape, therefore stands as a final destination for both the famous and the forgotten, the revered and the reviled.

It bears witness to Brighton’s rich history, offering a resting place for those who shaped its story and those who were just passing through.

For me, it is also a place of personal reflection.

The funerals of my parents and grandparents were held in the same chapel that hosted Aleister Crowley’s unorthodox ceremony.

It is where I also intend to end my journey. In this beautiful garden of the dead, the past and the present, the living and the dead, come together for one, final encounter.

Have you visited Woodvale Cemetery? Tell us your thoughts in the comments section below!