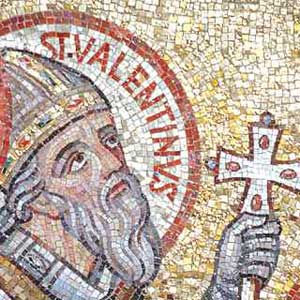

In this St Valentine’s Day Special, Jacob Milnestein reveals the mystery behind St Valentine – the patron saint of love, whose remains are in Ireland

There is scarce mention of St Valentine in the original Roman hagiographies. While renowned today as the patron saint of that most thoughtful and painstaking secular celebration, St Valentine’s Day, the original saint for who it was named is little more than a footnote in those first calendars.

He is an insignificant martyr, a later addition to a record rife with stabbings, beheadings, beatings and torture.

Yet for many centuries following the explosion of his popularity in the 3rd century, Valentine became synonymous with the traditions of 14th February his feast initially seemed designed to supplant.

Like Excalibur – allegedly traded by Richard the Lionheart for armies to fight the Third Crusade to King Tancred of Sicily – the popularity of his legend made remnants an artefacts of this possible saint an important icon in medieval pop culture.

Of the most significant of a saint’s icons is often the earthly vessel, the vacated shell remaining following his or her ascension through pain and martyrdom.

It is these remains of St Valentine that Pope Gregory XVI allegedly bestowed upon the famed Irish preacher, Father John Spratt in 1836 in recognition of his oratory talents.

Another of these artefacts, a small yet important glass vial allegedly containing the saint’s congealed blood, was also awarded the preacher and both returned with Father Spratt to Dublin, where they were later installed in Whitefriar Street Church alongside a letter of authenticity from the Papal authorities.

Despite contest from sites in France, Austria, Malta, and even Glasgow and Birmingham, it has become a custom at Whitefriar Street Church to exhume the remains of the long dead martyr every February and display that which has been left behind to remind the faithful of the solemn duty of marriage and sacrifice.

Like many other saints bartered and traded across Europe since the Dark Ages, the presence of alleged physical remains for the beheaded saint are a cunning piece of propaganda.

Used to illustrate the significance of Christianity role in uniting a couple in holy matrimony, the myth of St Valentine is a reminder that the church was once present at every step of the way in the life of the individual; from birth, through adulthood and marriage, and finally to the cold grave.

Yet should this subtle suggestion of authority prove too much to stomach, this writer, whilst incapable of presenting relics or spots of dried blood decorated in a Dublin church, urges the reader to remember a different sort of Valentine at this time of year.

Whilst rooted neither in the pagan Roman tradition or the later imported faith still present with Ireland and the British Isles, the 1st century Gnostic theologian, Valentinus provides a fine example of another way of looking at the relationship between believer and church.

READ: Saint Valentine, Heartbreak and Haunting in Ireland by Ann Massey

JACOB MILNESTEIN writes stories. His most recent story, “lecteur de tarot” can be found here.