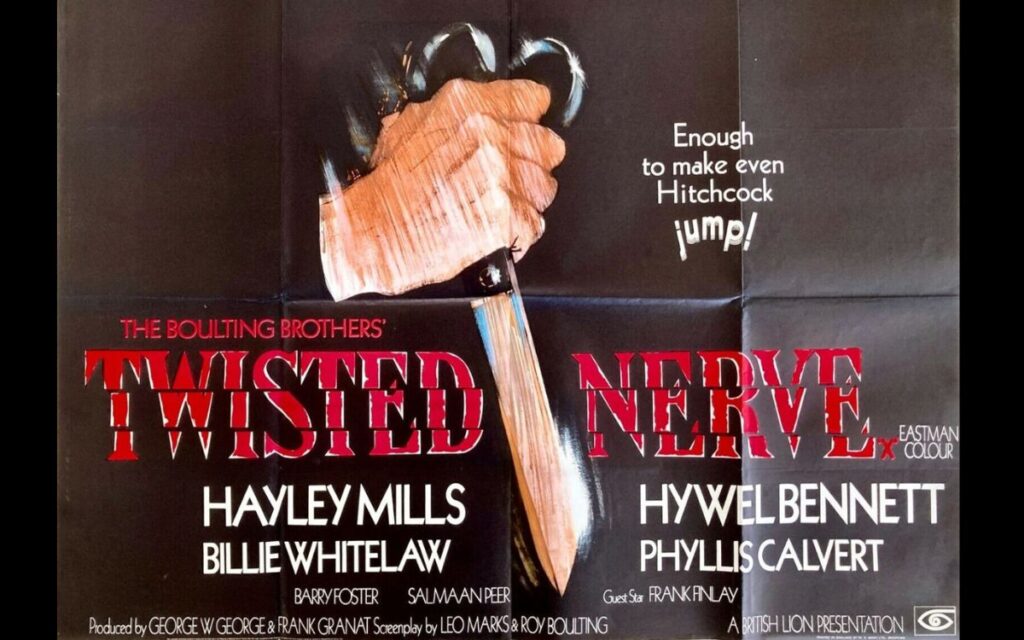

Twisted Nerve 1968 is a complex and enduring thriller, albeit problematic due to its controversial themes, writes DAVID DENT

TITLE: Twisted Nerve

RELEASED: 1968

DIRECTOR: Roy Boulting

CAST: Hayley Mills, Hywel Bennett, Billie Whitelaw, Phyllis Calvert, Frank Finlay

Review of Twisted Nerve 1968

The roots of the Boulting Brothers’ 1968 shocker Twisted Nerve can be traced back to the cinematic spectres of two ground-breaking films released at the dawn of the 1960s: Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

The UK film industry, while sensing an opportunity to cash in on the success of the latter film, was speedy but cautious in its response; specifically Hammer Films developed of a roster of motion pictures which may have aped some of Psycho’s shock tactics but steered away from the more sadistic aspects of Powell’s film; movies like Taste of Fear (1961), Maniac and Paranoiac (both 1963) and Nightmare (1964).

Twisted Nerve’s narrative inspiration may also have stemmed from an earlier source: Karel Reisz’s 1964 UK screen adaptation of a 1935 play by Emlyn Williams, Night Must Fall, starring a young Albert Finney as Danny, a killer who inveigles his way into the life of his boss’s daughter.

In the second half of the decade production of such movies had slowed in the UK (although there was a concomitant rise elsewhere in Europe with the growth of the ‘giallo’ genre in the same period); it was therefore perhaps surprising that John and Roy Boulting, following a string of comedies, satires and a comedy drama (1966’s The Family Way) should return, for their next project, to the murky world of the psychodrama.

Perhaps even odder was their choice of scriptwriter for this project; former World War II cryptographer and Bletchley Park employee Leo Marks, who had controversially written the screenplay and the original story for Peeping Tom.

The ’twisted nerve’ of the title (taken from a line in a poem by George Sylvester Viereck, a favourite of Marks, and quoted in the film) belongs to Martin (Hywel Bennett, fresh from starring in The Family Way, and keen to put a dent in his pretty boy image), although it isn’t a nerve that’s twisted; it’s a chromosome.

Martin’s brother Pete (who remains largely unseen in the film) has Down’s syndrome – referred to throughout as mongolism in the parlance of the day – and has been committed to an institution by the brothers’ mother, Enid (Phyllis Calvert), possibly on the advice of her new husband, the short tempered Henry (Frank Finlay).

Henry is also keen for stepson Martin, who still lives at home and has an unhealthy attachment to mummy, to flee the nest.

Whether as a result of his difficult home life, or something more medically dubious (of which more later) Martin’s peculiarities quickly make themselves known when, in a scene set in a department store, he ‘transforms’ into Georgie, becoming a six year old boy in the body of an adult male.

This act of conjuring up a simpleton is designed solely to innocently introduce himself to Susan (Hayley Mills, also from The Family Way, similarly keen to shrug off her wholesome image by accepting this role), a librarian who’s in the shop at the same time. Martin shoplifts, is rumbled, and Susan and Georgie are introduced; Martin’s choice of target seems random, which makes subsequent events even scarier.

Susan lives with her mother Joan (Billie Whitelaw) in a large house, the rooms rented out to disparate single male lodgers like grubby Gerry (Barry Foster) and quiet, studious Shashie (Salmaan Peer).

Into this odd setup Martin, as Georgie, manages to secure a room, his legitimacy vouched for by Susan. Once installed, Martin oscillates between his two personas (for the benefit of audience understanding) and proceeds to murder anyone who stands in the way of his new girlfriend, who is of course completely unaware of the man-child’s alternative identity.

The rather prosaic, suburban setting of the movie – a combination of actual west London locations and rather sterile Shepperton studio sets – adds a chilling ‘ripped-from-the-headlines’ contemporaneity to the whole thing.

The scientifically concluded suggestion in the film, which justifiably caused controversy at the time and has dogged it ever since, is that Martin’s mental health issues are linked in some way to his brother’s learning disability, and that psychopathy and criminal behaviour are therefore related to Down’s syndrome and can be passed genetically through faulty chromosome structure.

Despite being limply refuted in the film both by a doctor (Russell Napier) and a hastily added voice over prologue (required by the production’s medical adviser, Lionel Penrose, who subsequently removed his name from the credits), the whole thematic thrust of the film supports the connection, as does Bernard Hermann’s idiosyncratic, inappropriately playful score with its by now infamous whistling motif; re-used in Tarantino’s Kill Bill: Vol. 1.

Whether Martin’s transformation is voluntary or involuntary remains unresolved, although the final shot of the killer’s blank face suggests that Georgie may have won out; a nod perhaps to the fate of Norman Bates in Psycho.

Within all the nasty goings on – can this claim to be the UK’s first ‘slasher’ movie?

Twisted Nerve 1968 is littered with observations about maleness, viewed through the prism of the potentially impotent Martin/Georgie, whether it’s randy blokes feeling up Susan at a party, or Gerry’s arch innuendo and calls for the necessity of sex and violence in entertainment; confusingly Martin, left to his own devices in his room, leaves a collection of male physique magazines lying around for his perusal, suggesting both homo-eroticism and, again, impotence.

The only time we see Martin potentially acknowledging his alter ego is when Susan gives him a book she has borrowed from the library; “what a load of crap”, he concludes as he flips the pages, full of stories of the ‘man-cub’ Mowgli.

Undoubtedly Twisted Nerve 1968 remains problematic all these years later, but its blend of oddness, domestic drama and bizarre comic touches, not to mention fantastic performances by Bennett, Mills and a great supporting cast, make it one to return to.

Tell us your thoughts about Twisted Nerve 1968 in the comments section below!

DAVID DENT has been interested in/writing about film for most of his adult life. David is the host of the media blog www.darkeyesoflondon.blogspot.com which is now in its 10th year and also published a short-lived fanzine version. David has written for We Belong Dead and Shindig magazines and the Bloody Flicks website, has contributed to a number of books and Blu Ray commentaries, and regularly introduces screenings of cult films on the London cinema circuit. He is currently researching a book on the film director Lindsay Shonteff. David is also one half of a musical duo Detronics, whose first album ‘All That I Asked For’ was released in 2022. The album can be streamed/purchased. David lives in south west London with his partner. He is working on adopting his next rescue cat. You can follow him on Dark Eyes of London Facebook Page and Twitter @darkeyesofldn.