Lancashire author Chris Newton has released a spellbinding new book just in time for Halloween. ‘The Fylde Witch’ is a dark and enchanting novel which seamlessly blends history, myth and magic as Newton tells his own version of the folk tales associated with the real-life ‘Witch of Woodplumpton’, Meg Shelton. The Spooky Isles spoke to him about the inspirations behind his latest offering.

SPOOKY ISLES: What made you want to write about Meg Shelton? What is your connection to the myths surrounding her?

CHRIS NEWTON: Being from the Fylde coast, I grew up enchanted by stories of Meg Shelton, though I never quite believed that she was the “evil hag” that those stories made out. The folk tales tell us that she used witchcraft to steal milk and food, yet history tells us that the woman buried beneath that boulder (whose real name was Margery Hilton) was very poor and lived “on a diet of boiled groats”.

When I was first planning out this novel, I wrote down everything I knew about Meg on a whiteboard, divided into two columns: “Facts” and “Myths”. It was very telling seeing the scant facts in isolation. What we have is a woman living in a deprived area during the Little Ice Age who was vilified for stealing food. When you think of the recent £30 school dinner scandal, and the upcoming cuts to universal credit, it is clear that very little has changed since Meg’s time.

The poor are still treated with contempt and disdain by the ruing classes, and the Fylde is still home to some of the most deprived areas in the UK. I wanted to write a book about poverty and misogyny, but I also wanted to write a book about magic.

Talking of magic, The Fylde Witch very successfully blurs the lines between fantasy and reality. To what extent is this the story of the real-life Margery Hilton?

This is not a historical novel in any sense. It is very much a fairy tale, and my character Meg Shelton is not merely an “alleged” witch, she is a witch; pointy hat, broomstick and all. Because, whilst I wanted to honour those scant facts surrounding Margery Hilton, and to write something which respected the many women and men who were persecuted and hanged for witchcraft in the 17th Century, I also wanted to honour the old legends themselves – and find the point where myth and history meet.

Let’s face it, who doesn’t love a tale about a woman who can shapeshift? Ultimately, ‘The Fylde Witch’ is about stories. It is about why we tell them, and why they are important.

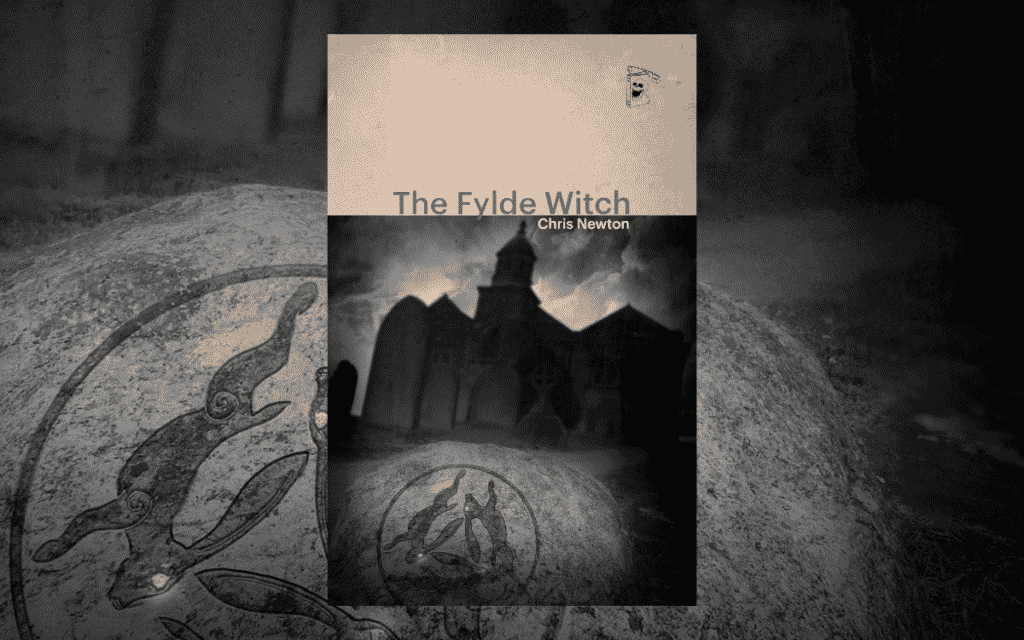

The book’s cover and the internal illustrations feature a Three Hares motif. Can you explain the significance of this symbol?

From the beginning, I knew this novel would be divided into three parts: maiden, mother and crone. Seeing as I was telling Meg’s life cycle, it seemed right to reference the Triple Goddess. Once I had that thought, the image of the Three Hares just popped into my head immediately.

One of the most famous stories about Meg Shelton is that she could turn into a hare – so this seemed the most perfect emblem to represent the three stages of her life. Traditionally, the image is presented as an optical illusion in that each hare seems to be drawn or carved with two ears, but on closer inspection, there are only actually three ears depicted in total. That idea of the three-in-one again evokes the idea of the Triple Goddess: three aspects united in one being.

The more I read about the symbol, and about hares in folklore generally, the more appropriate it became. I discovered that Meg is not the only witch in legend who is said to have taken on the form of a hare which, in a roundabout sort of say, becomes a plot point later in the book – the idea that the same tales keep manifesting in different places and cultures.

As well as their connotations with witchcraft, I discovered that hares were once believed to be the ghosts of forsaken girls returned to haunt their ex-lovers which, by pure serendipity, is another of the main themes in ‘The Fylde Witch’.

On the subject of the Three Hares, I should mention that they were realised beautifully for the book by my friend and long-time collaborator, Mark Hetherington, who is an incredible artist.

You mentioned not believing that Meg Shelton was the “evil hag” of legend. It’s easy to imagine that you might have chosen to depict her in a totally sympathetic light, but your protagonist is quite a grey character in many respects. What informed this portrayal?

I wanted to give her a voice, and I wanted her to have autonomy. As I mentioned, I held the legends as sacrosanct and chose not to contradict any part of the Meg Shelton mythology. So yes, she did do many of the “wicked” things she was accused of, but my job as a writer was to show her motivation for her actions.

I think to portray her as too sympathetic would have been to make her a victim. There are a plethora of books about “witches” who were, in reality, poor, oppressed, women and whilst I wanted to acknowledge and honour those victims I didn’t want to write another one of those books.

I wanted to write a fairy tale – albeit a very dark one. My Meg Shelton is the archetypal strong northern woman, and she has a reason for everything she does. Whether or not they are good reasons, and whether her ends always justify the means I leave up to the reader to decide.

Naturally, the book begins with her as a young girl and follows her into old age. It often felt as though I were writing a superhero origin story. Although, of course, it could just as easily be a supervillain origin story depending on your point of view.

It sounds as though you’ve always had this story in you. How long have you been working on it?

I suppose I have always had it bubbling away beneath the surface. For a very long time I was trying to write a Meg Shelton short story. Every few years I would re-write it as a fairy story, a horror tale, a historical drama, yet none of them worked.

It wasn’t until last October when I wrote a poem about Meg – ‘The Witch of Woodplumpton’ – specifically for Spooky Isles’ Halloween poetry page that the penny dropped. I realised that what I had to say was too complex and too expansive to condense into a work of short fiction and that, if I was going to tell her story, I had to tell her entire story.

At that moment the book tumbled, almost fully formed, into my head and it did very much feel as though it had been there all along. In fact, I was so absorbed by it that I didn’t actually get round to submitting my poem, so I was very pleased you were able to feature it this year!

Ultimately, I’m from Lancashire – Witch County. I’ve always been obsessed with witchcraft. My Dad and I would often go walking up Pendle Hill when I was growing up. We also spent a lot of time in Lancaster, where I later lived. Around Pendle and Lancaster, there are ‘Pendle Witch Trail’ signs, which depict pointy hatted witches astride besoms. You absorb that as a child and, in your mind, magic becomes as real as car parks and fairgrounds. Witches must exist – they’re on signs.

No matter how much you learn about the horrific reality of England’s witch trials as you get older, that formative connection will always be there, that inherent belief in the supernatural. It was inevitable that I would write a witch novel and – whilst I thoroughly enjoyed writing a Pendle Witches story for the Spooky Isles ‘Shadow of Pendle’ anthology – there was only one witch I could write a novel about. I was born and raised in the Fylde, and Meg Shelton is OUR witch. I think we owe her a legacy.

Meg Shelton is one of the lesser-known Lancashire Witches. Why do you think it is that the story of the Pendle Witches is more infamous?

I think it’s the fact that the Pendle Witches were tried and executed, and that those confessions still exist. You can literally go and sit in the cells at Lancaster Castle and say, “this is where Demdike died”. Factually, less is known about Meg Shelton because she was never caught, as it were. Plus, the motivations for, and political ramifications of, the witch trials themselves are a hugely significant part of British history. You can’t talk about the Pendle Witches without mentioning King James.

Meg Shelton’s story is, I suppose, less significant, but that doesn’t mean that it’s less important. That’s what I was channelling when I was writing the book: Meg understands her place in the world, she has a duty to one small corner of the it, but she feels that connection fiercely, because it is hers. But then we’re back to the idea of hares in folklore and stories cropping up time and time again: I’m taking old ideas and telling very personal, localised, new versions of them.

I did a huge amount of research for this book – but ended up trimming a lot of the historical detail in the edit. You don’t need to know where the Fylde is, and you don’t really need to know much about English history to appreciate the story. All you need to know is that there is a village in the countryside and, like any good village in a fairy story there is a witch’s cottage in the woods on the outskirts.

Once again, you’ve referred to ‘The Fylde Witch’ as a fairy tale, yet it’s very much marketed as a Folk Horror. Which is more accurate?

I very much consider it a dark fairy tale. Tolkien famously likened fairy stories to nursery furniture, in that it wasn’t specifically made for children, but ended up in the nursery because the adults weren’t using it anymore. Fairy tales or fantasy stories were never originally indented for children yet, post-Disney, I think the term has certain connotations now. ‘The Fylde Witch’ has some graphic content and some very adult themes, so I wouldn’t want to be accused of marketing it for children!

Genres and labels can be a bit of a curse, really. My band, Dischord, are labelled as ‘punk’, which is sometimes accurate as we often play loud, fast music – but then sometimes we play witchy folk songs. There are certainly horror elements to the Fylde Witch, but then there is a lot of fantasy in there, too.

I do love the term folk horror, though, despite the fact that nobody can quite decide exactly what it means. Ultimately, for me, it’s about our connection to the land; our fear of the elements and the suspicion that we’re only another petrol shortage away from being back in the stone age. So many aspects of ‘The Fylde Witch’ seem like quaint old traditions, but they were much more than that to the people from this area at that time, I have tried to present their beliefs as sincere and important, and most of their rituals and superstitions are closely connected to the land.

It’s easy to be dismissive of that, but when you consider that many folk would not survive a cold winter, and others would starve if the crops failed, you can see the need for certain ceremonies and rituals which honoured nature.

Lastly, of all the stories about Meg Shelton – which is your favourite?

I have written elsewhere on The Spooky Isles about my introduction to Meg Shelton when my dad took me to see her grave on Halloween 1998, and the story that sticks in my mind from that day is the story in which she steals corn from Singleton mill. Determined to catch her out, the miller made a point of counting his sacks of grain one evening. Later that night, when he rushed in to catch her in the act, the witch was nowhere to be seen. Yet, when he counted the sacks, he saw that there was one extra.

Triumphantly, he seized his pitchfork and plunged it into each sack in turn until one of them screamed and Meg Shelton appeared in its place. She snatched up a conveniently placed broomstick and took off into the night sky. I always liked to imagine he saw her silhouetted against a full moon, so I was very pleased to be able to include that detail in my re-telling of the tale. But, as ever, it may not have happened the way you think it did…

The Fylde Witch is available now in paperback and eBook from Safety Pin Publishing. And in eBook from Amazon.