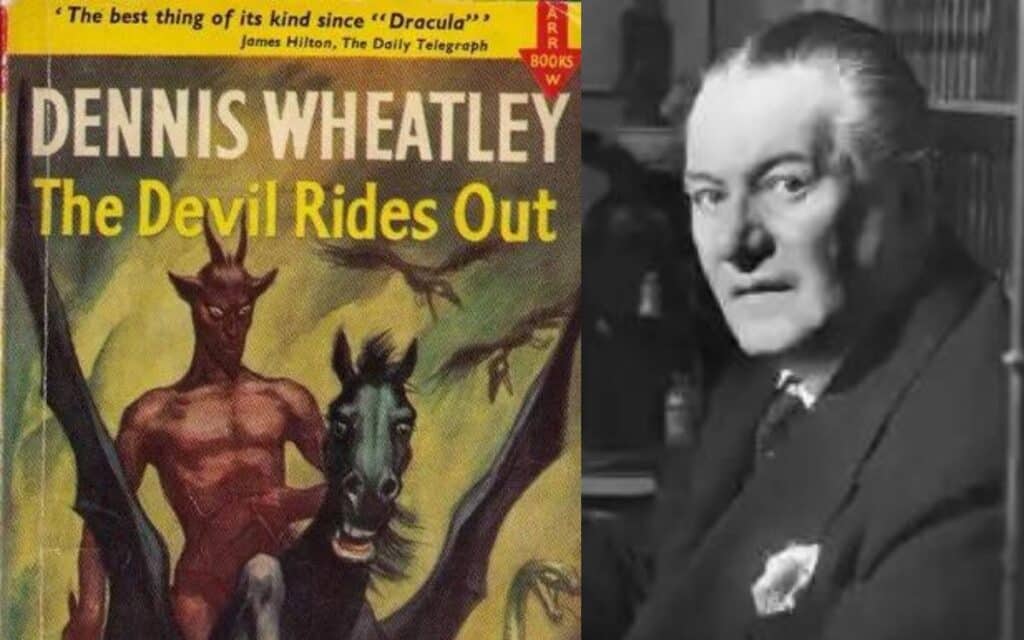

CHRIS NEWTON delves into the differences between the book and film versions of The Devil Rides Out, highlighting changes to characters and plot, and discussing Dennis Wheatley’s influence on British horror.

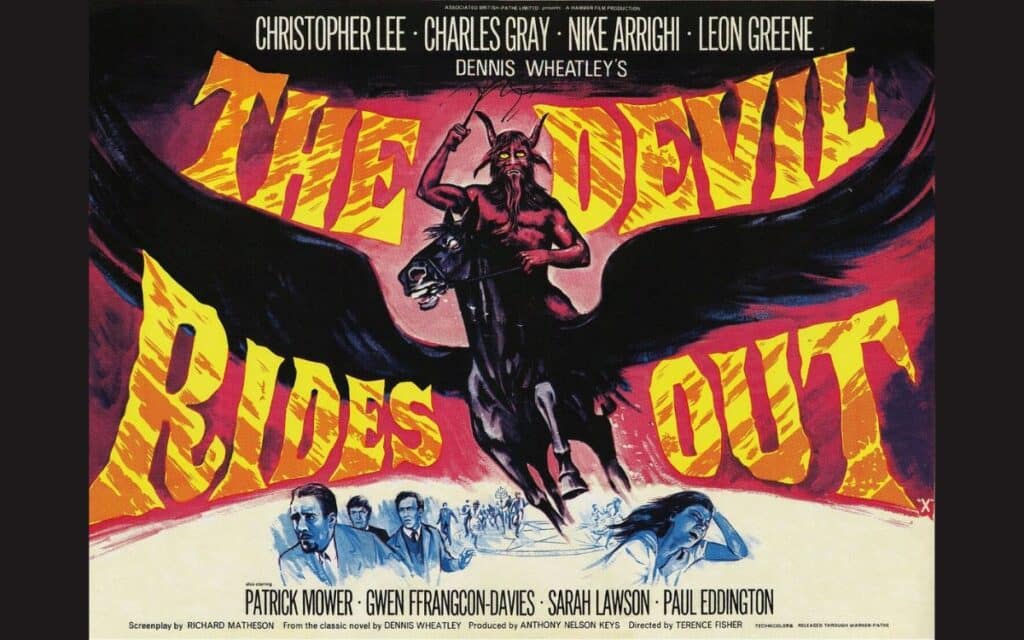

For the April episode of mine and Mark Charlesworth’s podcast, A Book at Breakfast, we’re talking all things The Devil Rides Out by Dennis Wheatley. To coincide with our discussion, I have put together a list of differences between the 1934 novel and the 1968 Hammer film production.

The Devil Rides Out: Differences Between The Book and The Film

The Characters

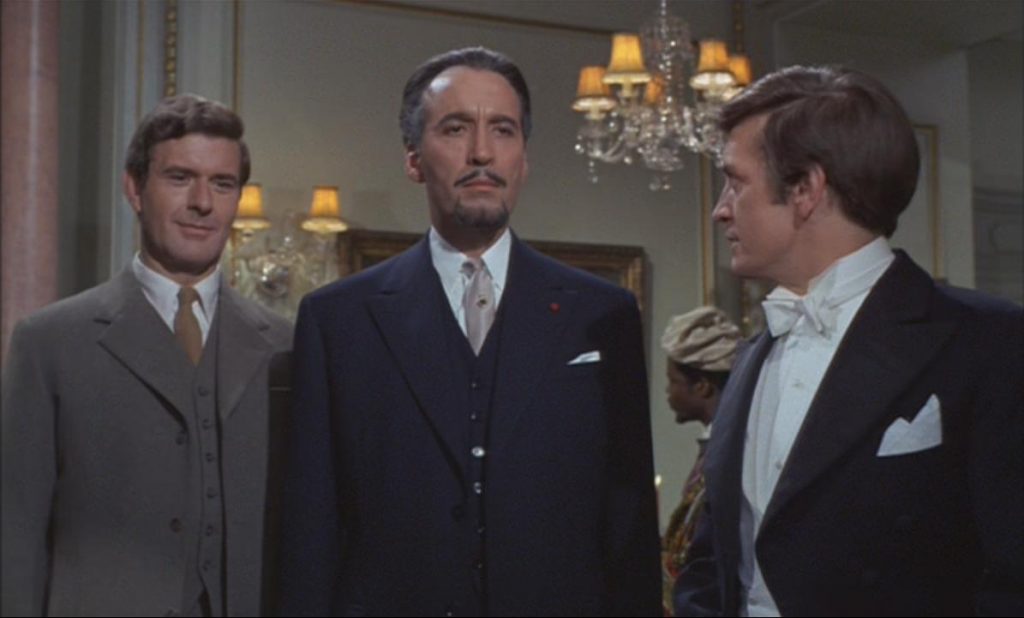

Whilst the book’s heroic Duke de Richleau is played fairly faithfully in a career-defining role by Christopher Lee, there are nevertheless some significant deviations from the source material. Most notably the character’s age.

In Dennis Wheatley’s novel, de Richleau is described as elderly Frenchman in semi-retirement as an ‘art connoisseur and dilettante’. Lee was only 46 when he played the part, and the character is aged down accordingly. In his later years, Lee frequently stated in interviews a desire to star in a remake of ‘The Devil Rides Out’ as an age-appropriate Duke.

In the film we can reasonably assume Monsieur la Duc is French, although Lee plays him with an English accent and his background is never explored. In the book, however, we learn much more of his origins. The elderly Duke is in fact an exile, having fallen foul of the French authorities in his youth because of his Royalist leanings. This plays a fairly significant part in the book’s climax when the protagonists pursue Mocata to Paris where de Richleau is recognised, arrested, and even shot at one point.

In the film, the Duke is given the Christian name ‘Nicholas’ whereas, in Wheatley’s novels, his full name was ‘Jean Armand Duplessis’ before he inherited the tile of Duke de Richleau.

Whilst Rex Van Ryn is largely unchanged in terms of his personality and role, the big difference is again his nationality. Wheatley’s Van Ryn is an American and heir to his family’s Chesapeake Banking and Trust Corporation of New York, which forms an integral part of the Paris plot which is entirely absent from the film. Curiously, Van Ryn is portrayed onscreen by Leon Greene, although the character’s voice was later dubbed by Patrick Allen (some of Greene’s original dialogue can still be heard in the trailer). Both actors were British, and neither of them played Rex with a US accent.

The book’s Richard Eaton is depicted onscreen very much as written, but his wife, the young Russian Princess Marie Lou, becomes the middle aged, English, ‘Marie’. Wheatley’s ‘The Devil Rides Out’ is a sequel of sorts to ‘The Forbidden Territory’, another book featuring the Duke, Rex Van Ryn, Simon Aron and Richard Eaton (the ‘Modern Musketeers’, as the author referred to them).

Whilst the plot of ‘Territory’ is unconnected to ‘Devil’ (the former is not one of Wheatley’s ‘Black Magic’ books), Richard and Marie Lou meet in Russia during the events of ‘The Forbidden Territory’. It could be that the Russian Princess element was dropped from the scripted story to avoid unnecessary explanation of the earlier book. The Eaton’s daughter, Fleur, is given the much more English name ‘Peggy’ in the film.

Simon and Tanith’s characters appear largely unchanged except for their physical appearances. Wheatley describes Simon as ‘frail’ and ‘narrow shouldered’, and Tanith as ‘golden haired’, neither of which can be said of Simon Mower and Niké Arrighi. The biggest deviation comes in the form of the main antagonist, Mocata himself.

Once again, the character outwardly appears to be English, whereas he is French in the book. And in complete contrast to the suave elegance and charm with which Charles Gray (who was 40 at the time) plays the part, Wheatley describes him as ‘a pot-bellied, bald-headed person of about sixty, with large, protuberant, fishy eyes, limp hands and a most unattractive lisp.’

De Richleau says that Mocata reminds him of ‘a large white slug’. Perhaps more interestingly, Mocata is given a backstory – and a first name – in the novel. In Paris, we learn that ‘Canon Damien Mocata’ was a priest in Lyons in his youth but left the church in scandal. According to de Richleau, only an ordained priest can perform a true Black Mass, making Mocata the ideal leader of a Satanist cult. Another of Mocata’s traits absent from the film is his penchant for sweets (there is even quite a funny exchange at the Eaton’s house regarding a box of chocolates) and strong perfumes.

Simon’s reason for joining the Satanists

In the film it’s never quite clear why Simon became involved with Mocata in the first place, nor why Mocata is so eager to get him back beyond the fact that their ritual will only work with 13 members present (in blasphemous mockery of Jesus and his 12 disciples). During the orgiastic Sabbat scene, both Simon and Tanith are visibly repulsed by the sacrifice of the goat and unwilling to partake in the ceremony… so why are they there?

According to the book, Simon was introduced to Mocata via a business associate, and his psychic powers saved Simon from potential bankruptcy when he predicted a financial crash. The more time he spent with Mocata, the more he fell under the Satanist’s hypnotic influence. Moreover, Mocata’s real interest in Simon lay in the fact that he is one of the rare people who were born ‘at a time when certain stars were in conjunction’, which makes him essential to Mocata’s invocation of Saturn coupled with Mars.

Despite the Walpurgis Night Sabbat having been foiled, we are told that Mocata can still perform the ritual while those two planets remain in the same house of the Zodiac. As Rex puts it, ‘the longer we can keep [Simon] out of Mocata’s clutches, the less chance he stands of pulling it off as the two planets get further apart.’

… and Tanith’s

Tanith is possibly the strangest character in the film. Until the very end, it’s never quite clear whose side she is on, such is Mocata’s hold over her. In the book she has a slightly more satisfactory – and tragic – backstory. A powerful psychic (and therefore incredibly useful to Mocata), at a young age Tanith had a vision that she was fated to die ‘before the year is out’, hence her journey down the ‘Left Hand Path’ to try and cheat that death or, if not, make the most of her short life.

She looks forward the upcoming Satanic festival as ‘an extraordinary experience.’ As she argues: ‘by surrendering myself I shall only suffer or enjoy, as most other women do, under slightly different circumstances at some period of their life.’

The film was released as ‘The Devil’s Bride’ in the US under the assumption that American audiences would think that ‘The Devil Rides Out’ was a Western. Whilst Christopher Lee has complained that the alternative title is meaningless, it presumably relates to Tanith, especially when – in the novel – she compares her giving herself to Satan to sacred prostitution, which ‘is still practised in many parts of the world,’ and considers her impending Satanic baptism as ‘a ritual which has to be gone through in order to acquire fresh powers.’

It’s not hard to see the allure of the Devil, especially when Rex tries to persuade her that she should be dancing and playing golf instead.

There is also a subplot involving an ‘old gypsy-woman’ named Mizka who nurtured Tanith’s magical abilities when she was a young girl. After Tanith has stolen the Duke’s car, she meets ‘Mizka’ – in reality a Dark Angel in the guise for her former teacher sent to lead her to the Sabbat – and is on her way to be re-baptised when Tanith’s long-dead mother appears as an Angel of Light and orders Mizka ‘back whence you came’.

Unlike the onscreen version of the story, Tanith never makes it to the Sabbat, and reunites with Rex the following day by throwing herself into a trance to divine his whereabouts. There is also quite a lot of time given to explaining that Tanith and Mocata share the same astrological number (twenty) and therefore their vibrations are closely attuned.

Black Sabbath

One of the reasons ‘The Devil Rides’ was not adapted for screen for more than 30 years was because of how taboo the subject matter of Devil worship was in England in all that time. Even by the film’s release in 1968, certain elements of the story were still considered controversial and either omitted or substantially toned down.

Wheatley’s Sabbat of saturnalian depravity appears onscreen as little more than a rave, its participants remaining clothed at all times and doing little more than eating and drinking. (Although, admittedly, some of them are drinking the blood of a sacrificial goat – and animal which, funnily enough, does not appear in the novel.)

The Satanic ritual, as described in the book, is more decorative for a start, with the leaders of the cult wearing ‘fantastic costumes’. One wears a cat cask complete with furry cloak and dangling tail, another is dressed as a ‘repellent toad’, a third wears a wolf costume and Mocata himself is a bat with ‘webbed wings sprouting from his shoulders’.

A far cry from the drunken dancing of the film, the book’s Satanists line up before the Goat of Mendes to perform the osculam-infame (‘the shameful kiss’, with which witches allegedly greeted the Devil by kissing his ‘other mouth’. I shall leave that one up to your imagination.) before the Goat dashes a cross against a boulder and then desecrates the host by ‘dancing and stamping fragments of the holy wafers into the earth,’ – and act of such blasphemy that the Duke himself has to look away.

If that isn’t enough, there is also cannibalism. Mocata and ‘half a dozen masters of the Left Hand Path’ sit at a head table before the Goat where they feast upon the flesh of ‘a stillborn baby or perhaps some unfortunate child that they have stolen’. The Duke’s suspicions are confirmed when a human skull is cast into a cauldron before the throne of the beast.

The revellers are also all naked, having shed their robes, and Wheatley spares us no description as the ‘huge-buttocked and swollen’ Madame D’Urfé prances ‘with some Satanic power’ as they ‘tumble upon each other in the disgusting nudity of their ritual dance,’ which, were it not for the intervention of Rex and the Duke, we are assured would have descended into ‘the foulest orgy, with every perversion of which the human mind is capable of conceiving.’

The Ancient Sanctuary

After rescuing Simon from his Satanic baptism, de Richleau and Rex take him straight to the home of the Eatons. In the book, the Duke insists that they find a sanctuary where they can keep Simon safe until the morning. (Even in the film we know that Mocata’s powers are only fully effective during the hours of darkness.)

With all the nearby churches locked up for the night, the Duke decides to take them to ‘the oldest cathedral in Britain’, and they spend the night at Stonehenge.

Conveniently, film-Simon is the only one of the Satanists not wearing ceremonial robes and remains in his three-piece suit throughout. In the book, he is not so stylish attired, with only the Duke’s car rug and great-coat ‘to cover his birthday suit’, and has to wait within the stones with de Richleau the next morning while Rex drives into Amesbury to buy him some clothes. As it happens, the only shop open is a sports outfitter, and Rex brings Simon some flannel shorts, a khaki shirt, checked woollen stockings, a cricket cap and a cyclist’s cape!

The whole Stonehenge episode allows for a break in the action for some much-needed exposition (most of Mocata’s plan, and Simon’s involvement in the ritual are explained here), but also some great comedy.

There is Simon’s ridiculous outfit (‘like the champion of next year’s Olympic games,’ as de Richleau teases him) and the three enjoying de Richleau’s trademark Hoyo de Monterrey cigars. Not a sacrilegious act in this ancient place of worship, as, the Duke assures us, ‘it is thoughts, not formalities, which make an atmosphere of good or evil.’

Mocata’s Plan

Beyond general evil and Devil worship, it’s not entirely clear what Mocata’s goal is in the film – and the reason for this alteration in the story is quite a heartbreaking one. In the novel, it is revealed that if Mocata can practise the ritual to Saturn in conjunction with Mars with someone who was born in a certain year at the hour of the conjunction, the whereabouts of ‘the Talisman of Set’ will be revealed to him.

With the Talisman, Mocata intends to open a gateway through which he can release the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. De Richleau explains that the Great War was a result of the horsemen having previously been let lose by Rasputin, ‘the greatest Black Magician the world has known for centuries.’

Bear in mind that the book was published five years before the outbreak of the Second World War, giving melancholic weight to de Richleau’s warning that ‘Europe is ripe now for any trouble and if [the Four Horsemen] are loosened again, it will be final Armageddon. This is no longer a personal matter of protecting Simon … We’ve got to prevent [Mocata] plunging the world into another war.’

When adapting the novel for screen in the ’60s, screenwriter Richard Matheson could no longer have the heroes on a quest to prevent the Second World War as, even if they defeated Mocata, the audience would know that they ultimately failed. It was Matheson’s idea to focus solely on that ‘personal matter of protecting Simon’.

In some respects, this is a better angle and gives the story more of an emotional heart – although it would be more satisfactory onscreen if the script had given Simon a believable reason for joining the cult in the first place and given Mocata a clear incentive to want him back.

Mayhem in Greece

Those who have criticised the Hammer film’s finale as being somewhat anticlimactic might have to be careful what they wish for when reading the novel. Instead of rescuing Peggy/Fleur from the occultists’ house which Rex discovered earlier in the film, our heroes head straight from Cardinal’s Folly (the Eaton’s Kidderminster home) to France in Richard’s private plane, and from there they follow a lead to Greece, which involves a twelve-hundred-mile journey across the alps to Yanina, after which ‘we’ll have to use horses’!

Why, exactly? Well, instead of the aforementioned house, the temple where Mocata plans to sacrifice Fleur to Satan is an abandoned monastery on Mount Peristeri (hence the horses). The movie’s deus ex machina reveal that the Satanist’s temple is a former Catholic church seems a little forced, but in the source material it makes more sense. The ritual must take place at the monastery, because this is where the Talisman of Set is buried.

What is the Talisman of Set?

According to Egyptian myth Set, the god of Disorder, murdered his brother, Osiris. Set tricked Osiris into lying in a coffin ‘fit for a king’ before nailing it shut, weighing it down with lead and casting it into the River Nile. Set then dismembered his brother’s body, cutting it into fourteen parts and scattering them.

Osiris’ wife, Isis, managed to find thirteen of those parts and successfully restored Osiris to eternal life. The missing fourteenth part? Osiris’ phallus. Yep. That’s what Mocata is searching for – an Egyptian God’s penis!

The Dread Sussamma Ritual

‘Almost, it seemed, the end had come. Then the Duke used his final resources, and did a thing which shall never be done except in the direst emergency when the very soul is in peril of destruction.’ – Chapter 27, Within the Pentacle

The iconic scene in the pentacle is very similar in both the film and the book. (Although instead of the film’s giant spider, they are menaced by a kind of demonic white slug – Mocata, perhaps?!) When the Angel of Death is summoned, de Richleau saves them by pronouncing ‘the last two lines of the dread Sussamma Ritual’.

This is very much built up as a last-minute resort, and we are warned that the consequences could be dire. (A classic case of ‘Whatever You Do, Don’t Do This!’ Or, to put it another way, ‘Don’t cross the streams!’)

As it happens, there don’t seem to be any consequences and when, later on, de Richleau is simply too scared to utter the invocation a second time, it is Marie – possessed by the spirit of Tannith – who guides Peggy/Fleur to speak the words. The Satanic temple is engulfed in flame and the Satanists perish, but again there are no discernible consequences for our protagonists. Or that’s how I always perceived it before reading the book.

The ending of the book is much stranger. Apart from the Monastery in Greece in place of the house in Berkshire, the general premise is the same. Mocata has abducted Fleur and is planning on sacrificing her, and the heroes race to rescue the child.

Instead of the repetition of the Sussamma Ritual, Marie Lou instead invokes an angelic being, one of the ‘Lords of Light’ who intervenes to defeat Mocata. De Richleau et al then find themselves transported beyond the physical world, until they are floating above their own unconscious bodies, still lying within the pentacle in the library of Cardinal’s Folly.

Clearly, the risk of the Sussamma Ritual was very real indeed, and in speaking it de Richleau has torn apart the fabric of space and time. Upon waking, the protagonists wonder if they have experienced some kind of shared dream. The implication seems to be that, during their pursuit of Mocata across Europe, the five main characters were, in fact, astrally projected versions of themselves. Fortunately, they succeeded and were successfully returned to their physical bodies.

The story is really quite neatly tied up here – the fact that time has been undone and the Angel of Death has claimed Mocata in place of Tanith means that Tanith’s prophesised death was both true and untrue. She was indeed fated to die before the year was out, but only in an altered reality, leaving her free to give her remaining days to Rex, ‘whatever their number may be.’

Having read this, the film’s ending has made more sense on subsequent rewatches. Interestingly, the Sussamma Ritual is mentioned but never quoted in the book, nor were those last two lines given in Richard Matheson’s script. It was Christopher Lee himself who researched the invocation. He could find no record of a ‘Sussamma Ritual’ and suspected it to be an invention of Wheatley’s. However, he did find a genuine charm to banish evil spirits, which he famously hollers in the film: ‘Uriel, Seaphim! Eo Potesta! Zati, Zata! Galatim, Galatah!’

On the DVD commentary to ‘The Devil Rides Out’, Lee explains that Uriel is an archangel – the second lowest rank of angel – whereas the Seraphim (‘the Burning Ones’) are the highest rank of angels. ‘Eo Potesta’ is translated as ‘I am the power’. De Richleau is literally calling upon the powers of light to do his will, just as Mocta pledges his sacrificial dagger to ‘All mighty and all-powerful Set’ (Interestingly, the only reference to Set in the entire film.)

If we take the book’s explanation that, during their dream journey, they were ‘living in what the moderns call the fourth dimension – divorced from time,’ then we can assume that everything that takes place between de Richleau’s incantation in the face of the Angel of Death and him waking up again within the chalk circle as having happened on the astral plane, then the words of the Sussamma Ritual serve almost as cosmic book ends to their out-of-body experiences, brought about by the ritual itself.

Racism

Despite its gripping pace, action and delightfully descriptive representations of devil worship and cult rituals, many of Wheatley’s values and attitudes have not aged well. Modern readers are advised to read with caution – or better still, read ‘Doctor Who and the Dæmons’ by Barry Letts instead!

As we’ll be discussing in our May episode of A Book at Breakfast, Letts’ novelisation of the classic Doctor Who serial The Dæmons is, in many ways, a re-write of Wheatley’s novel but given a decidedly sci-fi twist. Suave, well-travelled, knowledgeable hero? Check. Hypnotic evil clergyman antagonist? Check. Young woman taken to be sacrificed to a horned deity? Check.

But that’s the thing with The Devil Rides Out, whilst the film has aged better than then book, Wheatley – despite his deplorable views on race – certainly laid the foundations for so much British horror that was to come in the latter half of the 20th Century and it’s interesting to revisit his work to see the origin of so much that was to follow.

What are your thoughts about the book and film versions of The Devil Rides Out by Dennis Wheatley? Tell us in the comments section below!

I watched The Devil Rides Out (on Talking Pictures TV) the other week for the first time in years! Enjoyed the film as much as ever. But it is a *very* long time since I read the book: like many of us I suspect, I read it when I was about 9 or 10 and needless to say it scared me witless at the time… Seeing the film again made me think to pick it up to read again and I’m going to seek out a copy. Thank you for this article, I really enjoyed it.

Katy, I think it’s all time for us to do a refresher of the book! Glad you enjoyed the article.

I have loved the film since as a 10 year old I watched it one Friday night on my little tv upstairs in my room. I thought all the occult stuff was the coolest thing ever 🤣 It’s true Christopher Lee is perfect in this. I really wish there was time for a remake but alas! The book I picked up on Amazon about 12 years back. Didn’t get round to reading it until last year.

Wow it’s a weirdly authentic slice of another world and time. I kinda got obsessed in finding all the things that would just not fly now. & there was a fair amount. I’m not one who wants to replace all this stuff because my parents were born in the 30s ( dead now ) and it’s very authentic. But to young modern people ( I’m 51 this may ) it will seem jarring and hard to believe.

– “that butler made me want to shoot him on sight! He’s a “bad black” if ever I saw one” – 😳

Younger readers be warned. It’s near the knuckle. But a great read for all that.