Guest writer WILLIAM STEWART reviews ‘The Films of Terence Fisher: Hammer Horror and Beyond’ by Wheeler Winston Dixon

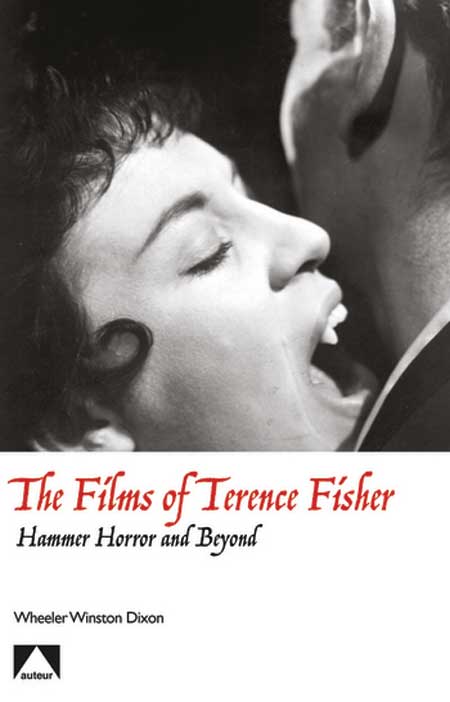

The Films of Terence Fisher: Hammer Horror and Beyond by Wheeler Winston Dixon is a 2017 republishing of Dixon’s seminal work The Charm of Evil: The Life and Films of Terence Fisher (published in 1991 by Scarecrow Press and long out-of-print) under the pretext of being revised, rewritten, and offering fresh critical insights into Fisher’s work.

His 1991 edition offered the first sustained critical study of all of Terence Fisher’s work in English, supported by interviews from Fisher’s widow conducted by Dixon in 1988, and challenged the critical parochialisms inundated by Fisher’s adulation as only a horror director.

Dixon’s perspicacity in illuminating on Fisher’s pre-horror films – having had the difficult task of locating 35mm prints of these films – through a careful découpage of each work helped situate Fisher’s films as an unique body of work and positioned the book as a vital resource for film studies in general.

Yet for those familiar with Dixon’s The Charm of Evil: The Life and Films of Terence Fisher expecting an entirely revised book and updated textual readings of Fisher’s work, as this new edition insinuates, will be disappointed.

The central criticism with this new edition is that, 26 years later, Dixon offers the same critical observations found in his earlier version with only some minor, superficial additions and amendments to make the text feel or appear fresh.

Over the last few years there have been more writings addressing Fisher’s work, yet their absence is felt here.

Indeed, in his supposed new research Dixon ignores inexplicably Terence Fisher (Peter Hutchings, 2001), Terence Fisher: Horror, Myth and Religion (Paul Leggett, 2002), the Spanish-language Terence Fisher (Joaquín Vallet Rodrigo, 2013), and Andrew Spicer’s essay “Creativity and the ‘B’ Feature: Terence Fisher’s Crime Films” (2006); even Denis Meikle’s two essays, “Fisher’s Folly or The One That Got Away: The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll Revisited” (2007) and “Mean, Moody, and Murderous: In Search of Hammer Noir” (2009) deserves mentioning.

By failing to incorporate, discuss, or challenge these works against his initial arguments, or perhaps re-address some of his concerns raised by these authors, Dixon instead insulates the book into a kind of scholarly bubble.

For example, Peter Hutchings views The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) as a film “much more aware of the nuances and complexities in its subject” (98) while Dixon still maintains his 1991 stance that “the originality of Gwynn’s and Fisher’s conception is undermined by the surprisingly stolid mise-en-scene […] yet the film has little else to recommend it” (217-218).

Or in The Stranger Came Home (1954), Andrew Spicer comments “the atmosphere, so economically created by Fisher, is claustrophobic and deliberately confusing, thick with guilt, suspicion, and possible betrayal” (36). Dixon sees no such atmosphere, maintaining his position that “the interior shots seem unusually cramped” and the film is not “powerful to save the rest of the work from becoming tedious and predictable” (160). In ignoring Hutchings, Spicer, and others, Dixon demonstrates a failure for academic growth in his new study of Fisher and, in doing so, helps reinforce the book’s apparent insularity.

Not all is negative, however. Since the first edition has been out-of-print for years and copies retail at exorbitantly high prices (indeed, one was listed recently at just over £300 on eBay), the real merit of this new edition is that it offers an affordable opportunity for film students, filmmakers, scholars, and Fisher aficionados to acquaint themselves with the early works and cinematic practices of Terence Fisher – a director delegated exclusively to the horror film and maligned unfairly by critics, yet a director that experimented and refined his craft from film-to-film until reaching, as Dixon suggests, a form of cinematic maturity with The Curse of Frankenstein.

Not a true revision of the original, yet this book succeeds insofar as Dixon’s readings of Fisher’s films are as scholarly as they are understandable by contextualizing the subtext of Fisher’s work into unequivocal cinematic language that demonstrates the director’s filmic command of the medium.

And that, no doubt, makes The Films of Terence Fisher: Hammer Horror and Beyond a valuable introduction to Terence Fisher for any cinéaste.

The Films of Terence Fisher: Hammer and Beyond is available from Amazon.

WILLIAM STEWART is a filmmaker born in Canada. Graduated with distinction from the MA Directing: Film & TV Course at University of Westminster in 2012. Three of his short films have screened at Cannes Film Festival. Favourite director is Terence Fisher. When not watching films, he’s binge reading Edgar Wallace and Dennis Wheatley novels. You can follow him on Twitter, Vimeo and Facebook.