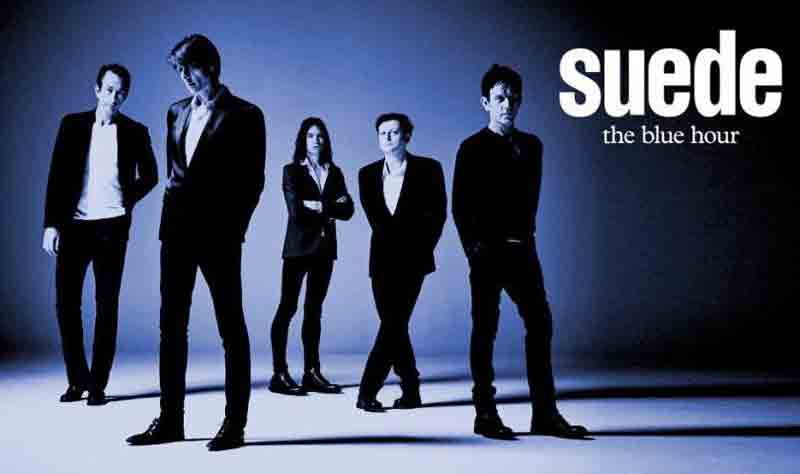

CHRIS NEWTON ponders the folkloric elements of Suede’s new album The Blue Hour – inspired by classic 1970s supernatural series, Children of the Stones…

On the 21 September 2018, Suede released their eighth studio album, ‘The Blue Hour’. Prior to the album’s release, they had described as an ‘English Folk Horror’

As a lifelong fan of the band (and horror, and folklore for that matter), I was intrigued to say the least.

The opening track, ‘As One’ was like nothing I had ever heard before. Part operatic art-rock, part horror soundtrack evocative of ‘The Wicker Man’ and ‘The VVitch’. And the discordant wail of its backing choir… What did that remind me of…?

The song is as unsettling as it is brilliant, with the vague overall narrative of a child wandering into the woods, beckoned by some unseen force as multi layered vocals chant “Here I am. Run to me. Come to me.”

The orchestral stabs and cries eventually give way to the sound of a frantic search party beating their way through bracken as they anxiously call out the name of the missing child.

In a recent interview regarding his memoir, Coal Black Mornings, Suede frontman Brett Anderson – describing his love/hate relationship with Britpop (a genre that Suede arguably started) – said that Suede ‘documented British life’, whereas subsequent bands ‘celebrated it’, which he considered to be a crucial difference.

Modern day Suede taps into folk horror and moves into the darkness

The swaggering glam-indie Suede of the early-to-mid ’90s documented British life in the suburbs, driving to clubs in taxis and purchasing pills in back alleys.

Modern day Suede are still providing a commentary, but this time with a firmly rural location. A community on the fringes of the wild. Interestingly, the titular ‘blue hour’ refers to the last vestiges of light before darkness falls, and with it all hope of finding the lost child.

It’s an interesting metaphor for the concept of small towns and villages on the edges of the woods, a last glimpse of civilisation before nature takes over.

There are other themes and characters and stories throughout the record; ‘Wastelands’ tells the story of two lovers sneaking off into the wild, called to escape the world by primal longing, whilst ‘All The Wild Places’ begins seemingly as a song about burying a pet, but as the narrative unfolds begins to give the impression that the dead ‘bird’ may actually be the narrator’s wife, as though a kind of lurking madness has taken hold of the people living ‘beyond the outskirts.’

I began to understand why they had called it ‘folk horror’. These themes tap in to something not only prevalent in British horror, but possibly the main ingredient for making something so quintessentially British. The US may have conquered the horror market, with The Conjuring franchise raking in over a billion dollars, but there’s never a sense that they take these things quite as seriously as we do. I’m frequently told that Halloween is ‘much more of a big deal’ to Americans. But when I see young trick-or-treaters dressed as cowboys and astronauts, I find myself doubting this. Perhaps it is (because the history of the native Americans is largely forgotten) that the majority of their own folktales and ghost stories are imported from elsewhere, enjoyed safely at a distance.

Here, in The Spooky Isles, we do not quite have that luxury. Our island is a very old one and there is a sense that perhaps, just perhaps, the creatures from these legends are real. They are still here. And they have not forgotten us. And perhaps the reason that films such as ‘American Werewolf in London’ and ‘The Wicker Man’ tap into our fear of closed-off, tightly knit rural communities is that we suspect that, cut off from the trappings of modernity, on the cusp of the wild – where ‘The Blue Hour’ takes place – the locals know about the old things which live in the woods. And worse, may be influenced by them somehow…

I remembered what Suede’s choir reminded me of. The atonal wordless wailing of Sidney Sager’s terrifyingly unnerving soundtrack to 1977’s ‘Children Of The Stones’, the most unsettling piece of children’s television ever made.

If HTV’s mandate was to ‘produce programming that reflected regional themes and interests’, I’m not entirely sure that ‘Children of the Stones’ was quite what they had in mind, but it reflected these rural themes of ancient, unknowable esoteric mystery nonetheless.

Adam Brake, an astrophysicist played by Blake’s 7’s Gareth Thomas moves to Milbury, a small Wiltshire village encircled by megalithic stones, with his son Mathew (Peter Demin).

Milbury bears a similarity to The Prisoner’s village with its picturesque quaintness hiding a sinister purpose, even down to the locals’ creepy catchphrase of ‘Happy day!’ But rather than a prison for former spies, Milbury – or rather, the circle’s – function is much more sinister, to use the villagers’ energies to draw power from a black hole. What’s scary about the village’s ever-repeating time loop of events is how ancient the knowledge that mapped the stars and aligned these stones is. Perhaps that fear of rural traditions isn’t fear of the unknown after all but the gnawing sensation that, deep down, there are certain truths that we have always known about our connections to the seasons and to the heavens themselves. As the main antagonist says: “Primitive cave-dweller? I think you do him an injustice. According to legend he was a visionary.”

Children of the Stone’s folktale within folktale

There is even a folktale within Children Of The Stones’ narrative, relating to a painting with an inscription which reads ‘Quod non est simulo, dissimuloque quod est’ (I deny the existence of that which exists). It depicts an ancient ritual, in which two outsiders come into the circle, outwit an evil druid in his attempts to harness the energy of the stones and narrowly escape only after the druids’ followers have themselves been turned to stone. There is an obvious parallel here with Adam and Mathew, and a sense that they are merely pawns in a never-ending cycle, much like the seasons or planetary phases.

In this current iteration of events, the role of the evil druid is filled by the sinister, charismatic and mysterious village leader Hendrick, whose house is – naturally – at the very centre of the circle atop a convergence of ley lines. Hendrick is played by Ian Cuthbertson in a performance that stands shoulder to shoulder with Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle. In fact, had this not been marketed as being ‘for children’ and been released in a serialised format, I think it’s fair to say that Children of the Stones could well have been regarded as one of the greatest – if not the greatest – British horrors.

When ordinary villagers are invited round to Hendrick’s for dinner they return changed, joining the ranks of ‘The Happy Ones’ which, occult astrology aside, encapsulates the key theme of Children of the Stones: the resistance to conformity. This show may not have been ‘educational’ in the way HTV intended, but the character of Mathew was a great role model to its young audience. As Stewart Lee said in his Radio 4 documentary ‘Happy Days’, the teenage characters in Children of the Stones, far from being arrogant know-it-alls were “…terrified of the world. They’re uncomfortable and alienated and alone.” This would make Mathew’s surrender to the Happy Ones understandable out of a desire to fit in, to be accepted, but his determination to fight against what he knows is evil is what makes him such a compelling protagonist, made all the more believable by the fact that he is not merely motivated by fear but intelligence and scientific curiosity. He wants to understand the true purpose of the stones in order to thwart Hendrick’s schemes, and his discoveries are delivered with an odd scientific accuracy thanks to the script supervision from Dr. Peter Williams.

Along with its non-conformist stance, another aspect it has in common with ‘The Prisoner’ is the significance of their locations, in that both ‘The Village’ and ‘Milbury’ feel like the main characters in their own shows, bolstered by the fact that they genuinely exist. It’s impossible to talk about Children of the Stones without mentioning Avebury, and it’s impossible to watch the show without wondering how much of it might be grounded in reality – or history at least. What rituals did the Neolithic people of Avebury practice? Who did they worship? And deep down, do we know? Have we always known?

We deny the existence of that which exists.

You can buy Suede’s The Blue Hour here.