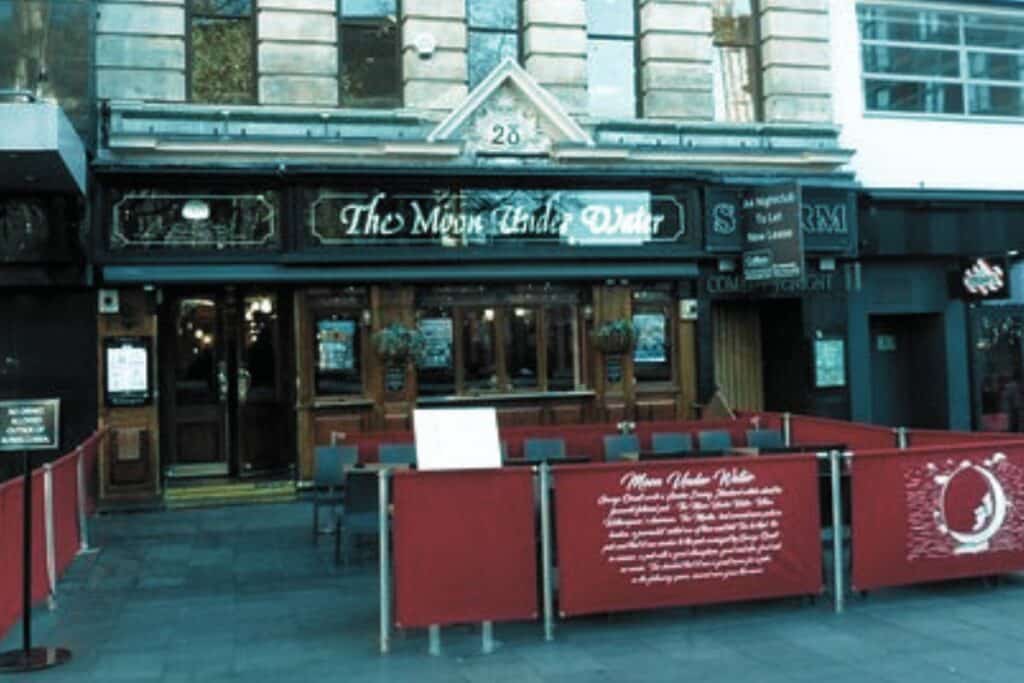

Above Leicester Square’s The Moon Under Water pub stands a stone arch, concealing the chilling legacies of John Hunter and the haunting tale of the Irish giant, Charles Byrne, writes DAVID TURNBULL

In London’s Leicester Square, just above the entrance to JD Wetherspoon’s ‘The Moon Under Water’ pub, there remains a stone arch which bears the number 28, marking the address of the original House which stood there. Around the corner, directly behind 28 Leicester Square, in Charing Cross Road, there is another property bearing the number 19 above its doorway. Both of these properties once belonged to the pioneering 18th century surgeon, John Hunter.

John Hunter and body snatchers

Hunter was born in Glasgow and originally came to London to work with his brother, William, who was also a surgeon. It was a period when members of the medical profession could legally procure the corpses of executed felons at a cost of around £10 for a cadaver. It was also a period when the demand outstripped the supply from prisons, giving rise to the practice of stealing fresh corpses from newly dug graves to be sold on.

It is said that William and John Hunter bought a huge number of illicitly purchased corpses. When John moved to his Leicester Square house, fresh bodies would be brought to by grave robbers to number 19 Charing Cross Road which was essentially the back door / tradesman’s entrance of the adjoined properties. Hunter would then perform public autopsies in his operating theatre situated at the centre of the adjoined properties.

This notion of a gentleman and eminent surgeon with letters after his name, whose London property has a back door which hides some dark secrets, was the raw material for the classic Robert Louis Stevenson London horror novel ‘The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’. The idea also provided inspiration for ‘Poor Things’, the 1992 novel by Alasdair Grey, recently made into a movie starring Emma Stone. In the plot Doctor Godwin Baxter is said to have once been a student of John Hunter. HG Wells, in ‘The Island of Doctor Moreau’ also suggests his scalpel bearing doctor had been a student of Hunter.

Hunter was not only a pioneering surgeon with a penchant for stolen cadavers. He was also an avid collector of curiosities. At his Leicester Square / Charing Cross Road property he established a museum in which to display his collection. Amongst various anatomical trophies he also had a stuffed giraffe, a two headed calf, a piglet born with two bodies and a specimen of a poisonous toad. It is here that Hunter’s path crosses with Charles Byrne, also known as the Irish Giant.

Who was Charles Byrne, the Irish Giant?

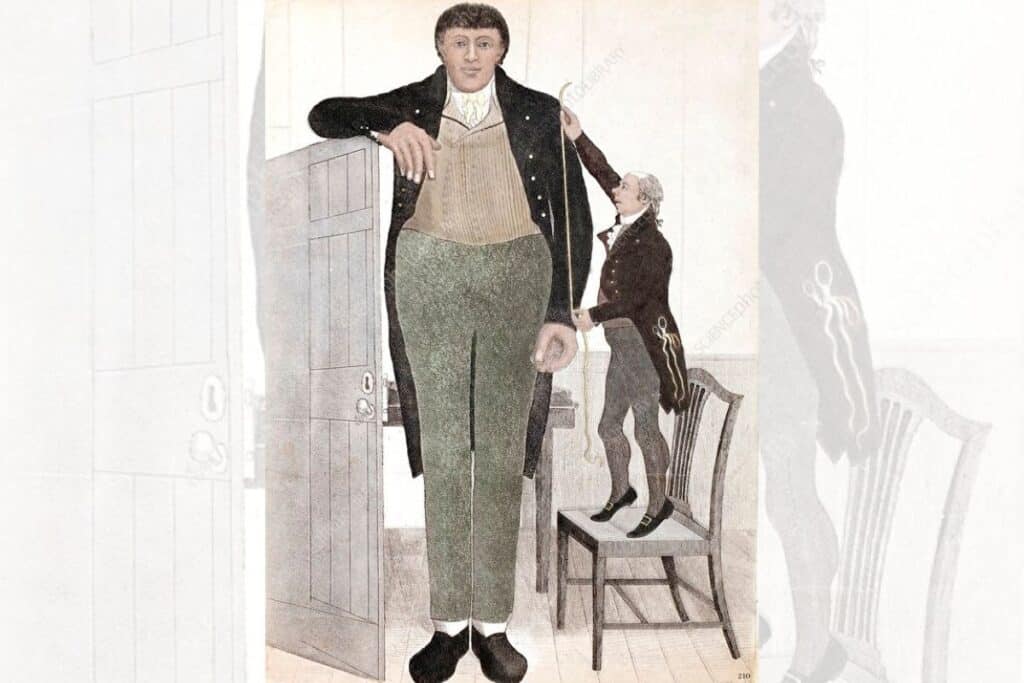

Byrne was born in Londonderry in 1761. He came to London when he was 21 and was soon the talk of the town, due to his extraordinary height. It was said that he could reach up and light his pipe from the streetlamps, which at that time were fired by whale oil and other similar accelerants. Reports suggested that he was between 8’2’’ and 8’4’’ tall. Medical evidence after his death showed him to have actually been 7’7’’, which is still pretty damn tall.

Much like Joseph Merrick (The Elephant Man) in the Victorian era, Byrne became a living specimen for the entertainment ladies and gents of late 18th century London, appearing as a live display at various addresses throughout the West End. One location was in Spring Gardens, just off Cockspur Street, close to where another museum, established by the jeweller and maker of automata, James Cox, once stood. A flyer published at the time describes Byrne as ‘the modern living Colossus, an astonishing part of the human species, who has already be inspected by members of the nobility and several of the Royal Society.’

One such inspection was by John Hunter, who became fascinated by Byrne, almost to the point of obsession. While in London Byrne’s size and the conditions related to it, which could not be accurately diagnosed at the time, caused a gradual deterioration in his health. When Hunter caught wind of this, he visited Byrne at his lodgings on Cockspur Street and tried to pay him a large sum of money in exchange for the giant agreeing that should he die, his corpse would be handed over to Hunter for medical study.

Byrne was appalled by the idea. To him the notion of his body falling into the hands of the surgeon would be shameful, putting him in the same category as the executed felons and murderers whose bodies had undergone autopsies in Hunter’s operating theatre.

So began a bizarre cat and mouse game.

In order to avoid any risk of his body falling into Hunter’s clutches Byrne devised a complex plan, accompanied by detailed written instructions. In the event of his death his remains were to be sealed inside a lead coffin, which was then to be transported to the coastal town of Margate. Here the coffin would be loaded onto a boat in order that he could be safely buried at sea

Hunter, however, was not a man to be thwarted. A few months later when Byrne died, aged 22, following the theft of his entire life savings, Hunter bribed one of Bryne’s friends to remove the body from the lead coffin and replace it with bricks. The huge corpse was then duly delivered, like so many other corpses, to the back door of the Leicester Square property.

The full details of what Hunter did with the corpse during his subsequent ‘studies’ are not known. But three years later it took pride of place in his museum, rendered to a huge skeleton. The affair caused a mixture of outrage and morbid curiosity amongst London society. But the eminent Hunter was never fully called to account for his actions.

After Hunter’s own death in 1793 the skeleton was bought by the Royal College of Surgeons. For over two centuries it remained on display in glass cabinet in what became known as the Hunterian Museum. It was only as recently as 2023 that the museum agreed, as a mark of respect, to cease displaying the skeleton. This followed a campaign which kicked off with an article in the British Medical Journal calling on the skeleton to be buried at sea in line with Charles Byrne’s wishes. A call supported by the Mayor of Londonderry and others.

The skeleton, however, remains in the possession of the Royal College of Surgeons, who are yet to act on their commitment to consider releasing it for burial. DNA taken from the skeleton has suggested that Charles Byrne suffered from a rare genetic disorder which caused his gigantism. Researchers have found four families in Ireland who carry the mutated gene and have suggested that its origins may lie with a single common ancestor going back around 60 generations. These may have included Patrick O’Brien from County Cork who stood at 8’1’’ and the bothers Knipe who were both 7’2″.

In her novel ‘The Giant, O’Brien’, Hillary Mantel recounts a fictionalised version of Charles Byrne’s life and his interactions with Joh Hunter. He’s also been the subject of a song, ‘A Short Ballad for a Long Man’, written by Irish folk singer, Seamus Fogarty, and a 2023 opera, ‘Giant’, by the composer, Sarah Angliss.

Watch A Short Ballard for a Long Man by Seamus Fogarty

Tell us your thoughts about this article in the comments section below!