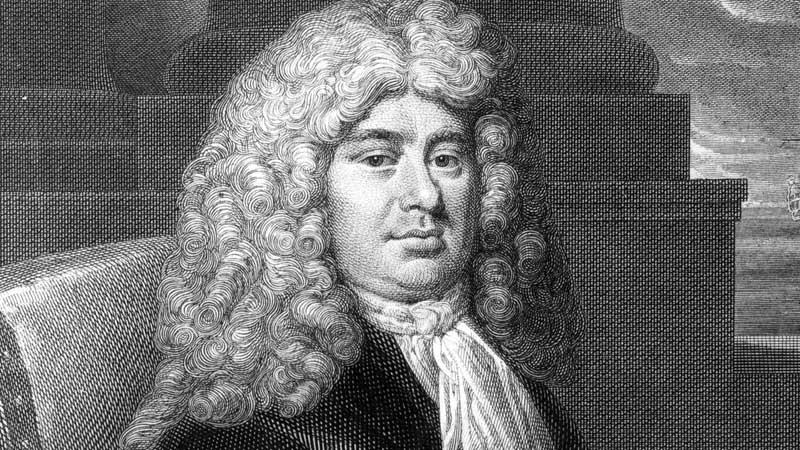

JON KANEKO-JAMES reveals the paranormal side of historic London figure, Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys was a civil servant living in London during some extremely important times: he witnessed the Restoration and the Great Fire of London. He saw the Enlightenment take hold, lived through the Great Plague of 1665, and the second Dutch War where the English burned the island town of Terschelling. He knew important people like King Charles II and the Earl of Sandwich. What people know less about was his fascination with the paranormal…

Samuel Pepys Collected Spells (And Stories Of Them Being Performed)

Despite being a man of the Enlightenment, Samuel Pepys was partial to a few of the magico-medical charms that were popular at the time. The end of his diary of 1664 contains a few, including a charm for ‘stanch of the blood,’ one for the pricking of a thorn, one for ‘the clap’ and one for what he only calls ‘the burning’ (considering how much of a philanderer Pepys was this might also be something against VD).

He also kept a lucky rabbit’s foot to ward off the colic, which he didn’t entirely believe in but found pretty effective nonetheless. Pepys even remembered the collector Elias Ashmole telling him about rains of frogs and insects in 1661, saying that they fell out of the sky fully formed.

But full-on spells were also of great interest to Samuel Pepys: in his diary of the 31st of July 1665, he describes a dinner with friends where ‘a very sober scholar’ called Brisband told him a tale of two little French girls in Bourdeaux.

Brisband’s story begins with the four girls whispering an incantation that began, “Royde come un Baston, Friod come Marbre, Leger come un espirit, Levons to au mon de Jesus Christ…”. Brisband describes the girls whispering one line of the spell each, going around in a circle, putting each a finger on a boy who lay on the ground, putting their fingers on his lips, until with just their four fingers they raised the boy in the air as high as they could reach and then laid him flat on the ground again as if he was dead.

Brisband tells that he was initially sceptical about the incantation, thinking that it was some magical trick the boy was in on, and so called his host’s cook, who was a large, no-nonsense man who they raised up in exactly the same manner and laid out on the ground.

He Was (Sceptically) Interested in Prophesy

Samuel Pepys was also great collector of prophesy, although he didn’t seem to believe much of it. In fact, he openly laughed at the Astrologer William Lilly:

“At dinner we discoursed of Tom of the Wood, a fellow that lives like a hermit near Woolwich, who, as they say, and Mr. Bodham, they tell me, affirms that he was by at the justice’s when some did accuse him there for it, did foretell the burning of the City, and now says that a greater desolation is at hand. Then we read and laughed at Lilly’s prophesies this month, in his Almanack this year!” – June 14th 1667.

Although many amateur (and professional) prophets did manage to predict the Great Fire of London, including the Anonymous author of 1610 tract Babylon is Fallen, a huge number of almanack writers had already written their 1666 books without a single reference to the fire whatsoever. Richard Saunders, an almanack writer of some note at the time, wrote that 1666 would being London a great year ‘which God’s goodness hath ratified to her, above many other places,’ even predicting another great year in 1667.

Astrologer John Booker had probably the best excuse, which was that an attack of dysentery had stopped him properly observing some comets in 1664 and 1665, which threw off his whole scheme of prediction. He also claimed that another astrologer called Vincent Wing had claimed a partial solar eclipse would affect the astrological influences of the moon (whatever Wing said as an astrologer, his astronomy was spot on: the moon passed the lower half of the sun on the 22nd of June 1666.)

Lilly, who caused Pepys the most amusement, took the safe route and pointed out the things that he’d gotten right: mocking the apocalyptic expectations of the Fifth Monarchists, saying, “What miraculous Thing or Change hath hitherto happened, in 1666, in Rome or Italy, either by fire or other casualty? There is no particular Antichrist, no Man of Sin revealed or discovered, more than in many foregoing years… Christ is not come down from Heaven to rule as a Temporal Prince upon Earth.”

Lilly also blamed a rogue comet passing through Taurus from Gemini that had thrown out his predictions for the years 1666 and 1667.

Again, though, Pepys did have experiences with Prophesy that he couldn’t explain: on Feb 3rd 1666 he talks about a burned piece of paper that was blown from London to Carnbourne in Windsor Forest, that read, “Time is done, it is done.” He even had his fortune told by a gypsy in 1663, and marvelled at how accurate the woman’s predictions were, although he remained unconvinced that she had any supernatural powers, as opposed her to just having a head for business (she advised him not to loan money to family members because they wouldn’t pay it back.)

He Read About Witchcraft

The times Samuel Pepys lived in were times when attitudes to witchcraft were changing. At the turn of the century witchcraft had been a fact, and King James I/VI had been an avid witch hunter in his native Scotland, presiding over the bloody Berwick Witch Trials in the 1590s. We know that Pepys was fairly sceptical about the supernatural: he called Midsummer Night’s Dream a ‘silly performance’… but that didn’t stop him being fascinated with the occult in many forms.

We know he bought Reginald Scott’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft when it was reprinted in 1665. Scott’s work was a skeptical tract about witchcraft, describing witches as:

“These miserable wretches are so odious unto all their neighbours, and so feared, as few dare offend them or deny them anything they ask… These go from house to house and from door to door for a put full of milk, yeast, drink, pottage, or some such relief, without the which they could hardly live… It falleth out many time that neither their necessities nor their expectation is answered or setved in those places where they beg or borrow, but rather their lewdness is by their neighbours reproved.

“And further, in tract of time the witch waxeth odious and tedious to her neighbours, and they again are despised and spited of her, so as sometimes she curseth one, and sometimes another, and from that the master of the house, his wife, childen, cattle, etc. To the little pig that lieth in the stye. Thus in process of time they have all displeased her, and she hath wished evil luck unto all them, perhaps with curses and imprecations made in form.

“Doubtless at length some of her neighbours die or fall sick, or some of their children are visited with diseases the vex them strangely, as apoplexies, epilepsies, convulsions, hot fevers, worms, etc., which by more ignorant parents are supposed to warn the vengeance of witches…”

Another witchcraft book that Pepys bought was Rev. Joseph Glanville’s Philosophical Considerations touching Witches and Witchcraft, which came out on November 24th 1666, when the ashes of the Great Fire of London were still cooling.

Glanville was very much in the same mould as we find Pepys: a relatively progressive thinker, but still a man of his age. He attended Exeter Collage, Oxford, and got his MA at Lincoln College by 1658.

He studied Natural Philosophy (i.e. Restoration era physics) at the same time as Robert Boyle and John Wilkins (who were both incredibly influential on modern science as we know it) and wrote a book of scepticism that landed him in a lot of hot water (mostly because it wasn’t just sceptical about science and pseudo-science, it was sceptical about the church and government too).

Even now, Glanville’s prose is better than anyone else writing in his time, but his scepticism about folk magic was mixed in with a fairly unshakable belief in witchcraft.

Glanville didn’t necessarily believe that there were human beings with supernatural powers, but he definitely believed that there were intelligent spirits in the air that could interact with the human world, and thought that Atheistic Materialism was a dangerous trend that would leave us defenseless.

But with all that said, Glanville isn’t a pants-on-head, fire and brimstone preacher like the German Heinrich Kramer (whose book, The Malleus Maleficarum, includes sections on penis-stealing witches), or the Witchcraft hating Holland brothers who might have influenced Christopher Marlowe.

Glanville is more of a Colin Wilson for the restoration era: he collects and retells interesting stories about magic, always being scrupulous to reference them and tell us where they came from. Not only that, but a lot of his work isn’t just about witches, it’s about Ghosts and Devils.

Which is probably why Samuel Pepys read his book, because they had one thing in common…

He Was Fascinated With A Haunted House

The thing that Samuel Pepys and Glanville both followed was the case of a haunted house in Tedworth. Pepys mentions the house in his diary several times, being a friend of Lord Sandwich (alleged inventor of the sandwich) who had been at the house and come away unconvinced of the ghost’s reality.

Glanville was a firm believer that the phenomenon was real, writing at length about it in his book (which might have been why Pepys bought it, rather than the witchcraft.) We can see that Pepys was more sceptical than Glanville. He recorded a conversation with his cousin, the Earl of Sandwich, who had been present during a demonstration of the phenomena in the Wiltshire house:

“Both at and after dinner we had great discourses of the nature and power of spirits, and whether they can animate dead bodies; in all which, as of the general appearance of spirits, my Lord Sandwich is very sceptical. He says the greatest warrants that ever he had to believe any, is the present appearing of the devil in Wiltshire, much of late talked of, who beats a drum up and down.

“There are books of it, and they say, very true; but my lord observes, that though he do answer to any tune that you will play to him upon another drum, yet one tune he tried to play and could not; which makes him suspect the whole; and I think it is a good argument.” – Diary of Samuel Pepys, 15th June 1663.

The story itself is worth telling: after confiscating the drum of a noisy vagrant with a fake passport, a local worthy called Mompesson found that his house was haunted by a strange spectre who patrolled the house and grounds banging on a drum. Mompesson even made a tour of the house with pistols in hand but was unable to deter the phenomena, which would come and go in a pattern of five night on and three nights off.

The phenomena most often came from outside the house, and wasn’t restricted drumming: after a while there was a wailing in the air above the house, with the phantom drummer particularly delighting in tormenting the children, who were very disturbed by the ghost shaking and hammering on their bed posts. Even when the children’s beds were hidden in the attic and they started sleeping during the day the ghost soon found them.

In fact, the ghost seemed to get particularly attracted the children. It spoke to them by the mechanism of anthropomorphic floorboards until their father forbade the spirit ‘such familiarities’; it created stench of sulphur so bad that the local minister and some of his parishioners came to pray away the spirit as a devil, only to have return a short time later. The spirit even continued to molest the children even after their beds were made up in the parlour, although only by tugging their blankets off and pulling their hair.

And the parade of phenomena didn’t stop: the spirit identified itself as Satan; it hid Mrs. Mompesson’s clothing and stuck her bible in the ashes; it lifted up the servants’ beds off the ground and dropped them again. One of the male servants even got into a sword fight with the invisible menace. Eventually the itinerant artist and drum-owner, William Drury, was found and sent to America for witchcraft, although he escaped the ship during a storm.

It also bore out that Samuel Pepys and m’Lord Sandwich were right to be sceptical: the memoirs of the 2nd Earl of Chesterfield record how Charles II blew the whole case open by questioning Mompesson, who confessed to having faked everything.

And Pepys, like many sceptical ghost lovers, was capable of scaring himself into moments of belief: in November 1667 he and his wife were frightened out of bed by scratching noises in the chimney that turned out to be nothing but a sweep, and in 1668 he says, “after supper we fell to the talk of spirits and apparitions, whereupon many pretty particular stories were told, so as to make me almost afeared to be alone, but for shame I could not help it.”

Pepys even spent a night in a haunted room. In 1638 a young Pepys spent the night in a room at Hill House in Chatham, where Kenrick Edisbury (a naval surveyor) was supposed to have haunted after death. The owner of the house, Sir William Batten, told Pepys a particularly lurid version of the story, which made Pepys, “…somewhat afeared, but not so much as for mirth’s sake I did seem…”

Comments are closed.