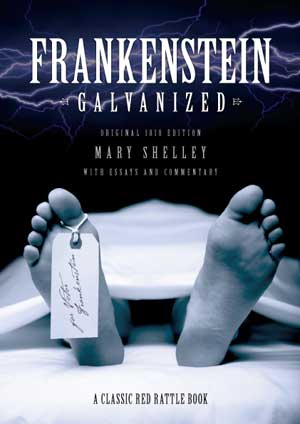

SARAH PARKIN reviews Frankenstein Galvanized, a new edition and essays on the Mary Shelley classic

For readers already familiar with Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, the title Frankenstein Galvanized will probably be confusing.

Of course, the idea of bringing the text to life is appropriate for this wide-reaching edition, illuminated by essays from a range of academic and non-academic writers.

But as the very demand for an edition of this nature demonstrates, the classic tale of the scientist who swiftly regrets his experiments in man-making isn’t actually dead.

The Creature lives nearly 200 years on…

It’s a phenomenon, and one that’s lasted for nearly 200: the continuing presence of Frankenstein and the Creature in popular culture has ensured a constant stream of new bindings and interpretations. If ever there was a saturated market, it’s this one, and any new edition of the novel has to work hard to find a gap to fill.

In many ways, then, Frankenstein Galvanized is already fighting an uphill battle, and the editor Claire Bazin’s ambitious intention to produce a volume “of interest to the general reader, the student and the academic” seems almost hopelessly naive. The fact that it succeeds even partially is therefore impressive.

An essay by a trade union leader nestles alongside the response of a professor (although the balance is still weighted towards theacademics) and the result is a genuinely interesting variety of perspectives.

An essay by a trade union leader nestles alongside the response of a professor (although the balance is still weighted towards the academics) and the result is a genuinely interesting variety of perspectives.

When the editor claims that “there should be at least one essay with which a reader can disagree”, it’s certainly true: whether that be Bazin’s own assertion that the birth of the novel is meant to “compensate” for the loss of Shelley’s first child, or the parallels drawn by Jim Mowatt with contemporary power structures.

They don’t even agree with each other – Samia Ounoughi emphasizes the significance of Robert Walton’s frame narrative, while Bazin dismisses it completely by claiming the text should start with Victor Frankenstein’s recollections. That’s a definite strength: it brings the reader into the debate and raises questions that are easily overlooked.

Where criticisms can be made, it’s actually mostly on the scholarly side.

Electing not to add footnotes to the novel to avoid disruption to the reader seems at odds with using in-text referencing for the critical material. Deciding not to reference the 1831 edition when it’s repeatedly quoted in the essays begs the question of how an interested reader should find it – editors aren’t meant to assume readers have Google.

The six endnotes stating the sources for Shelley’s poetry quotations hardly constitute the “commentary” promised on the cover. For the academic or student, it won’t dislodge the Oxford World’s Classics or the Penguin editions, though I doubt that was ever the intention.

As a way of introducing both text and context to those who only know Boris Karloff, though, the world could do far worse.

SARAH PARKIN in West Yorkshire and Durham, where she is currently studying for a Masters degree in English Literature at Durham University. You read Sarah’s series on Mary Shelley here. You can follow her on Twitter here.