Ratcliff Highway Murders are the most horrific London crimes you’ve probably never heard of. TREVOR BOND tells us about the East End massacre that predated Jack the Ripper by almost 80 years….

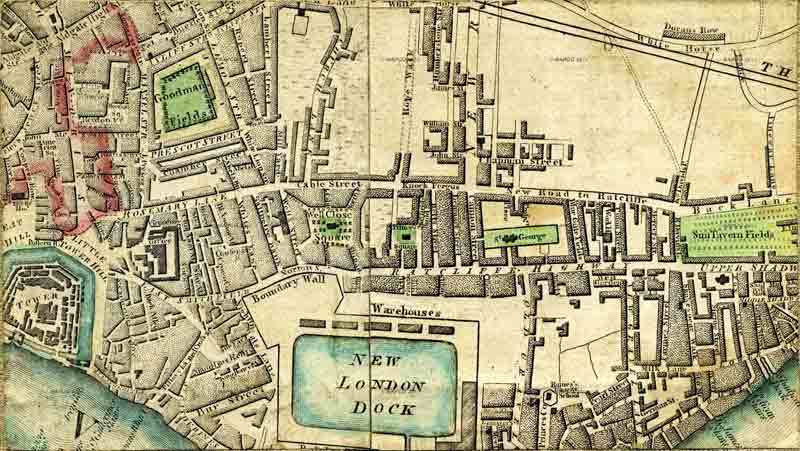

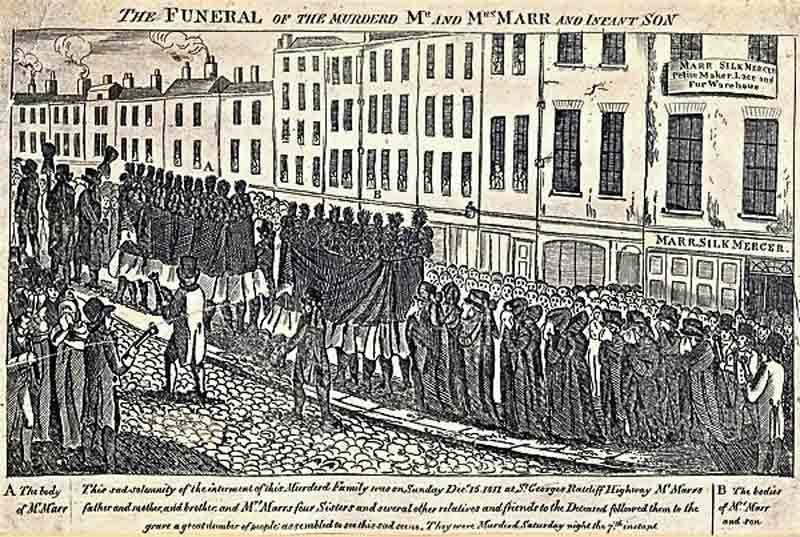

At 10.30am on New Year’s Eve 1811, a huge crowd gathered along the streets of Shadwell, St George’s, and Wapping in London’s East End, in the shadow of the Docks.

They had gathered to witness a funeral procession – a funeral procession with a difference.

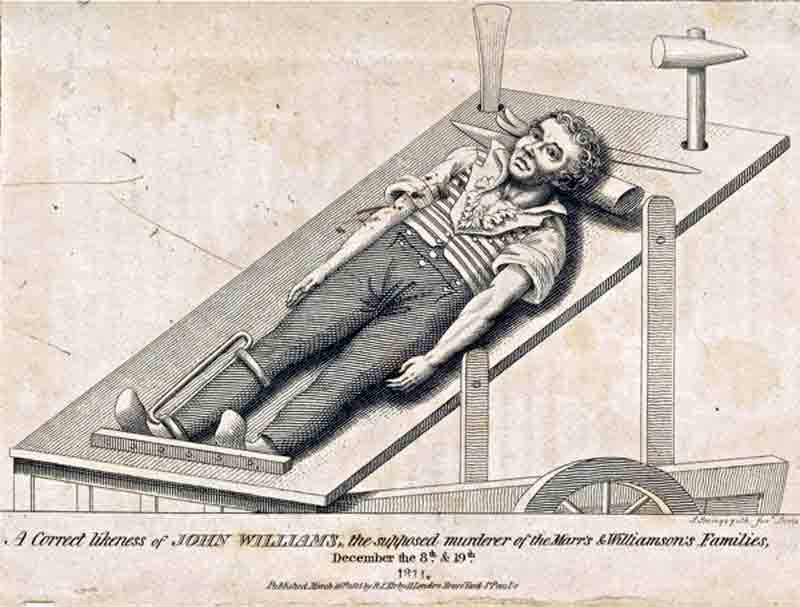

The man whose body was displayed on a cart, dressed in blue trousers and a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up, exposing his already decaying arms, was a sailor named John Williams.

He had been arrested eight days earlier on suspicion of no less than seven brutal murders; five days later he was found hanged in his cell at Coldbath Fields prison, Clerkenwell.

In his absence, Williams had been declared guilty and sentenced to form the centrepiece of a gruesome spectacle.

Now his three-day-old corpse was due to be wheeled through the streets to a crossroads, buried in a hole in the ground and covered in quicklime, with a stake through its heart.

How the Ratcliff Highway Murders began

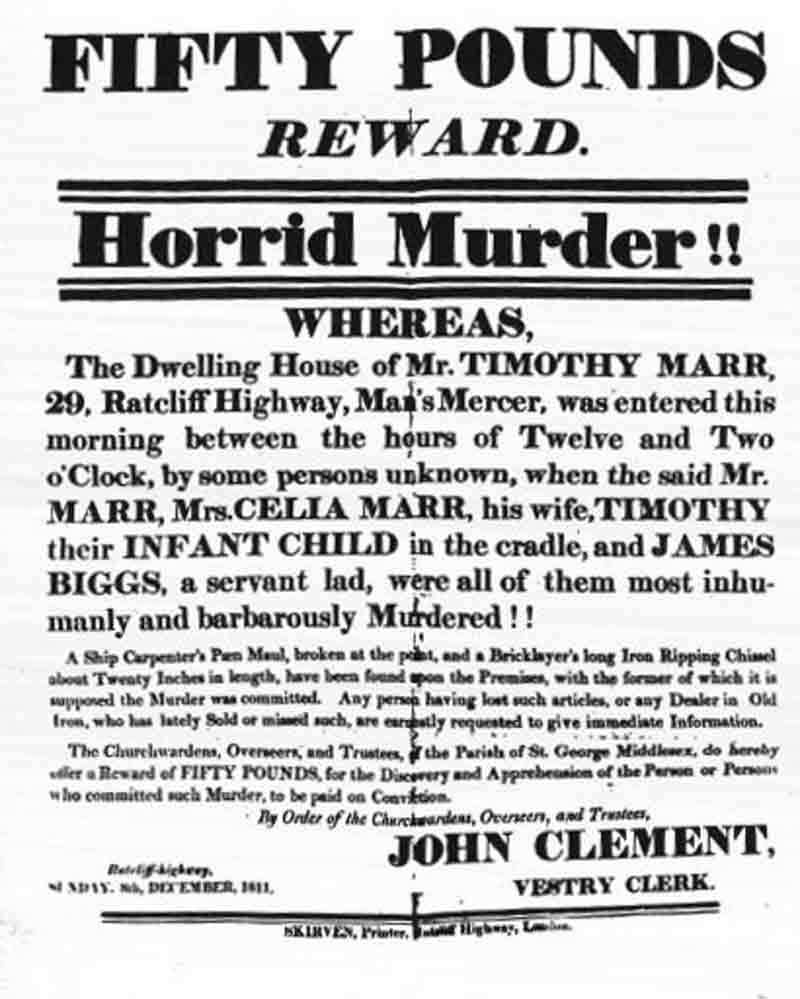

The whole sorry tale had begun on December 7th, when draper Timothy Marr set about shutting up his business on Ratcliff Highway around midnight.

Also present in the property were Marr’s wife Celia, the couple’s recently born son, also named Timothy, and James Gowan, Marr’s apprentice.

Servant Margaret Jewell, however, was absent, sent out into the night to purchase food (specifically oysters) and also settle a bill at a nearby bakery.

Ratcliff Highway, a unsavoury place

Ratcliff Highway had already earned an unsavoury reputation, and had the events of that night taken a different turn, it may have been reasonable to expect that a lone woman wandering the area on a dark winter night was at much greater danger than her employer and his family ensconced in their home.

In the time which it took for Jewell to realise that a brace of oyster vendors and the bakery had all closed for the night, however, Marrs’ shop had been broken into.

Intriguingly, if not immediately alarmingly, on returning she found the front door locked.

She would also later recall hearing footsteps inside the shop. Still, no one opened the door to her knocking.

A scene of unimaginable horror

When the police and a neighbour forced entry into the premises, they were met by a scene of unimaginable horror.

James Gowan and Celia Marr lay dead on the floor, bleeding profusely; Timothy Marr was found behind his counter in a similar state.

All three had been bludgeoned to death – using, it was later presumed, a bloodstained hammer which was located in the couple’s bedroom.

A subsequent examination of the shop suggested that this was not a case of robbery, but other than the hammer few other clues as to what had transpired could be unearthed.

There was to be one final gruesome twist, though, when Timothy Marr Junior was discovered in his crib, his head battered and his throat cut. He was 14 weeks old.

Despite the offer of substantial rewards for information, the pre-Metropolitan Police investigators had little to go on.

And then, less than two weeks later, a remarkable sight greeted onlookers in nearby New Gravel Lane just after 11pm on December 19th.

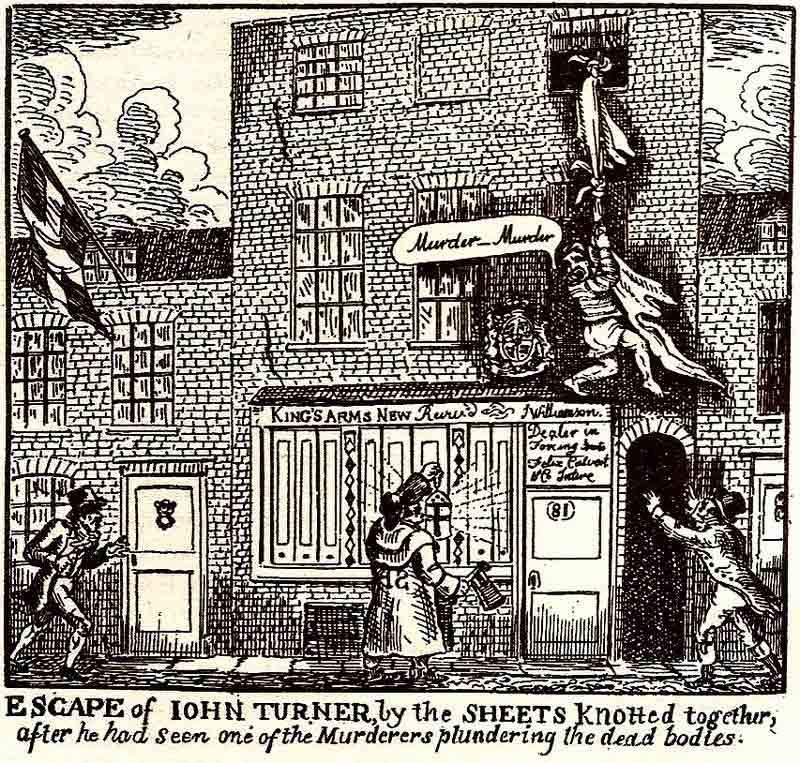

John Turner, a lodger at the King’s Arms pub, was escaping from an upstairs window, crying and shouting and either partially or wholly naked depending on the source. It was clear that something dramatic had happened within.

Once again, entry was gained and horrors discovered.

Inside were the bodies of the publican, John Williamson, his wife Elizabeth, and barmaid Bridget Harrington – once again all battered to death, and on this occasion each with their throat cut.

Crowbar, chisel murder weapons

The weapons used would appear to have been a crowbar, found on the premises, and something sharper, which had also cut into John Williamson’s hand – perhaps a similar implement to the ‘ripping’ chisel which had earlier been found at Marr’s shop, although free of any incriminating bloodstains.

The public were by this time terrified – and furious.

In turn the authorities – whose numbers now included Bow Street Runners and the Thames River Police – could have been forgiven for feeling flustered, even panicked.

Doubtless much to his relief, Turner was able to satisfy investigators that he was not the culprit, as was John and Elizabeth’s 14-year-old granddaughter Catherine Stilwell who seems to have remained asleep during the carnage around her.

John Williams, who lodged at another nearby pub, the Pear Tree, and who regularly drank in the King’s Arms was not to be so lucky.

When a maul was found to be missing from a chest at the Pear Tree, which also housed a ripping chisel, and a fellow lodger there told how Williams had supposedly returned home with a bloodied shirt on the crucial night of the second set of murders, his fate was all but sealed. He was arrested on December 23rd.

Newspapers had little doubt of his guilt

The newspapers seem to have held little doubt that he was the Ratcliff Highway killer; whether it was a sense of inevitable injustice or a guilty conscience that led him to take his own life before legal judgement was passed is a mystery which died with him.

When John Williams’ body took its final journey, there was concern over whether the level of public sentiment might boil over into violent unrest, however, in the event the occasion was, for the most part, marked by solemnity.

As his body was tipped into the hole, however, the noise levels were said to rise significantly.

The recovered maul and chisel were displayed alongside his body on the cart – the former being used to force the wooden stake through his dead heart.

Conclusion

It would be 77 years before another series of East End crimes would shock the world in a manner comparable to the ‘Ratcliff Highway Murders’ – with the notorious 10-week spree of ‘Jack the Ripper’.

Today, the former sensation has been largely forgotten, although in 1971, famed crime fiction author P. D. James, working with police historian T. A. Critchley, wrote ‘The Maul and the Pear Tree’ and argued persuasively within for Williams’ possible innocence.

Comments are closed.