A six-week spate of stones raining down on 19th Century Truro caused a supernatural frenzy among its residents, writes MATTHEW E. BANKS

Cornwall has always been a land of superstition, where fairies, knockers, witches, and ghosts roam freely. These deep-rooted beliefs are as much alive today as they were in the far distant past.

Scholars like Bottrell, Hunt, and Courtney in the mid- to late-19th century collected the folklore and legends of Cornwall so that they would not be lost to time.

As the Industrial Revolution moved forward, bringing industry and science to the forefront, there was a clash between the new beliefs of modern man and the old superstitions that had not faded away, and it was into this clash of beliefs that the rain of stones happened.

Truro in the early 19th century was the hub of the industrial revolution in Cornwall.

It was not yet the Cathedral city that it would later become, but farmers, ships, and a whole host of other workers descended on the city for both trade and work.

As the city grew, new parts rose out of the dirt and mud. One such part was Carclew Street, where a newly built house was hired as a depot for the arms of the militia regiment of Royal Miners.

The house next to that belonged to the sergeant-major of the regiment, a man called Candy.

These attached houses were open at the front and rear. On one side were several newly built and uninhabited houses, and on the other were the barracks where two troops of the 16th Lancers were stationed.

It is here on a Wednesday evening in April 1821 that our story takes place. Sergeant Thomas Ashburn, a former non-commissioned officer of the 6th Regiment who had been severely wounded in the head in Portugal.

As a result of that injury, he suffered from both depression and paralysis.

For the past 11 years, he had been the armourer for the regiment. He resided at the property with his wife and six children, the eldest two having recently joined the family (in 1819) after living with their maternal grandmother in Preston, Lancashire.

Edward was 17 and his brother Thomas was 16, and their time with their grandmother was not a happy one, as every day she would send them to work at a cotton factory, where they worked 15-hour shifts from 6am through 9pm.

Once their father summoned them, life became very different for them.

By 1821, Edward had been an apprentice to a Mr Guthrie, a currier, for about a year, and Thomas Jnr was domestically employed by his mother, but the coercion and discipline that both parents brought to reform their children’s manners drove Edward to run away once and Thomas Jnr repeatedly.

On this particular night, Ashburn was taking care of the arms when he was suddenly alarmed by the breaking of windows of the house.

Running to the door, he could not see anyone throwing stones and could not figure out where they were coming from.

The stones continued to fly at intervals, shattering numerous panes, not only in the depot but also in the adjoining house, where the sergeant-major of the regiment resided. Yet none of the surrounding properties were struck!

Both Candy and the armourer, being scared, rushed to other officers’ residences in the town, who, upon their return to the depot, saw the stones striking the houses. Every attempt to find the cause or the precise spot from which the stones fell from failed.

This rain of stones continued through the night, and it was reported by the neighbourhood people that “the stones were directed by no mortal hand.”

Driven to despair, the mayor (and magistrate) were called upon, and with two active constables, they hastened to the depot.

They were followed by a growing group of people, eager to witness the proceedings, with whisperings of devilry, witchcraft, and ghosts.

Newspaper reports Stones Raining on Truro

As The Royal Cornwall Gazette wrote: “A very singular but very mischievous system of annoyance has been carried out for the last day or two, by a person or persons not yet known, who have been amusing themselves by breaking the windows of a house [ ] In the day time as well as at night stones of no common size have been thrown at the windows and panes of glass broken, and although many persons have been present, the place from whence these missiles were thrown has not yet been discovered.

“Various conjectures are afloat on the subject, not altogether unmixed with idle superstitious notions… [ ]…a reward offered for the apprehension of the mysterious offenders, and we heartily hope they will be discovered and punished.”

Despite the fact that the miners regiment, the police, and a great crowd had gathered and were all looking for the source of the stones, nothing was found, not even when the stones fell not towards the front but at the rear of the properties.

The stones even ‘decided’ to rain down upon the mayor and his assistant, while they tried in vain to keep not only the peace but the gossip under control.

Eventually, guards were placed at various points, and the windows of both properties were barricaded on the outside with boards.

The stones continued to fall, but at intermittent times. The strain of this occurrence caused Ashburn to collapse, and his friend and fellow officer Edward Milford was called for on the morning of 4 May as others feared that Ashburn was going to die. Milford found his friend insensible, his pupils fully dilated and his body convulsing, finally bursting into a violent flood of tears upon seeing Milford.

Ashburn managed to become sensible for a while, stating that he thought that he was dying and that he wished to die. Milford managed to get Ashburn to his house, where the regiment surgeon opened up the temporal artery and placed a ‘blister’ over his head, and as Milford stated, “He has since been carefully attended by my people and by some of the non-commissioned officers of our regiment who do not believe in witchcraft and an evil eye.”

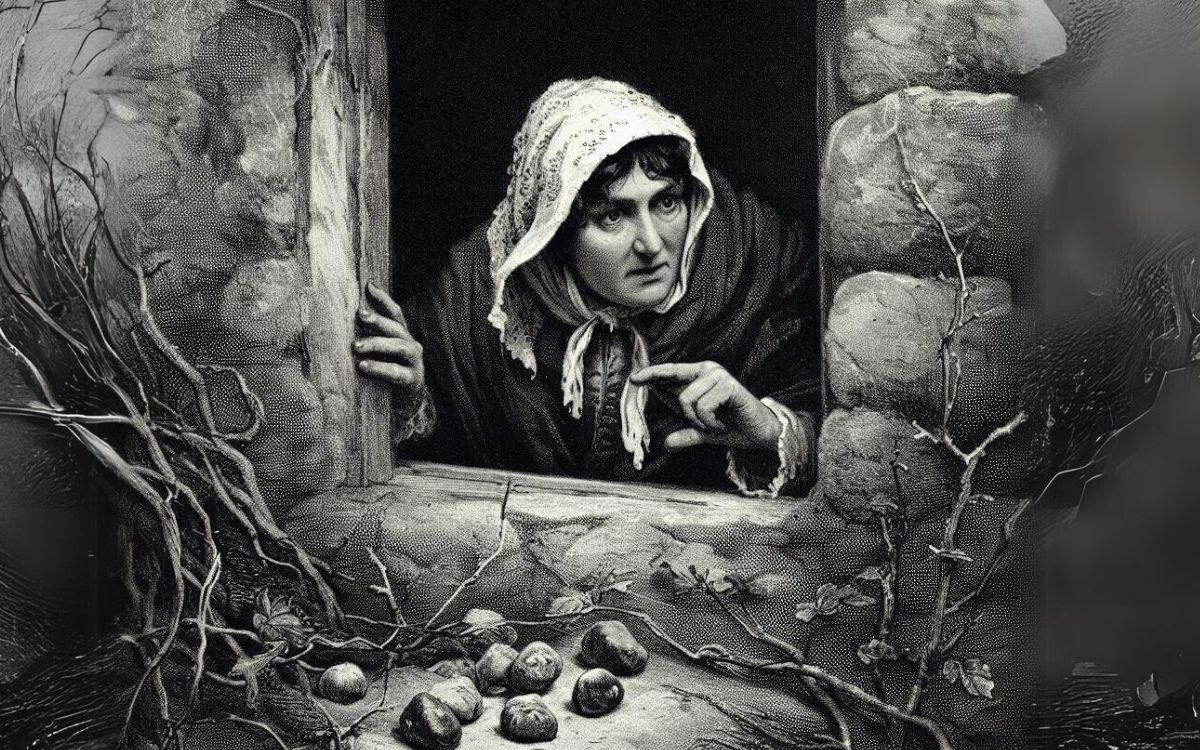

While Ashburn was recovering and the talk of devilry and witchcraft was reaching fever pitch, a woman was chased through the streets of Truro by a pack of boys and girls, who had every intention of ripping her gown off and drawing her blood so that she might not have any power over them. (It was a common belief at the time that drawing blood from a witch would prevent them from witching anyone else.)

Constables were able to calm the situation down. Once Ashburn was feeling a lot better and had recovered enough, he decided to move his family back to their house, and upon arrival and opening his property, Ashburn was shocked by what he saw. Lying in the middle of the floor was his looking glass, which he had used to shave, broken with its back out and placed on the frame with the shattered glass upon it and stones scattered around it. More incidents like this happened over the course of days.

The armourer, driven by desperation, moved from the depot and found lodgings for himself, his wife, and their children on Charles Street. He had scarcely moved when plates and glasses were shattered and a clock on the wall was damaged, “all at a single blow!”

A teapot flew into the air and shattered upon the floor. The armourer’s wife became hysterical, saying that she believed that ‘something had followed her!’ And it was recorded that that was the general opinion of all the inhabitants in the immediate neighbourhood.

Because of this, the armourer’s wife was sent back to her quarters in Carclew Street, where it appears that the ‘ghost’ had either preceded her there or followed; either way, the stones fell again and the crockery was destroyed. It got so bad that two constables descended upon the property and pledged that nothing would happen in their presence without detection.

At the very peak of this rain of stones, where superstition was reigning supreme, the cause was discovered. On Friday, April 14th, Edward Milford was called upon again, but this time it was Thomas Jr. that he hastened upon. Thomas Jr. was at Trebilcock’s the bakers, apparently having a similar seizure that his father had previously suffered. Milford found him in bed, his eyes shut but his limbs movable. Concluding that the boy was fabricating, he informed Thomas to get up and stop pretending.

When this failed, Milford threw some water into the boys’ faces, and he opened his eyes but carried on the pretence. Milford turned to Sergeant Sampson and asked him to get a horsewhip. Sampson quickly obtained a small wooden cane, which Milford applied to the boy’s sides and shoulders. Thomas Jr jumped up, crying and exclaimed that he was having a fit, but when he realised that his ruse was caught out, stopped.

The reason for this ‘seizure’ was because Milford and others, on strong evidence (I.E. the boy was caught throwing a stone) confronted him earlier that Friday and accused him of being the cause of the rain of stones. Ashburn Sr by this point had fallen into a deep melancholia, believing that he and his family were at the mercy of some supernatural persecution which worried both his friends and colleagues.

On 10 May, it was reported that Thomas Jnr had confessed to being the mysterious stone thrower, that he had committed this rouse on his own. The reason that he gave for this was that his mother abused him.

He stated that she continually beat him with a fire poker and on one occasion she hit him with a broom so hard that his head bled; and that she frequently told him that she would ‘kill him.’ So he took his revenge on both parents as one refused to protect him (his father) against the other (his mother) and turned a blind eye to these daily verbal and physical beatings.

This confession was made in the presence of a Dr Taunton, a Mr Thomas Powell, a Mr Budd and others on the afternoon of 10 May and so brought to an end after six weeks of fear of the unknown the scandal of the rain of stones. This would not be the last time that Cornwall would be hit by another ghostly haunting scandal, for 35 years later The Ghost of Wheel Alfred would dominate both the newspapers and village gossips alike.

Tell us your thoughts on this article in the comments section below!