Professor Pepper brought showmanship brought ghosts to the Victorian stage, says ANDREW GARVEY

The Victorians had a curious relationship with the afterlife.

One marked by wild swings between fascination and fear. In polite society at least, bound by strict rules of etiquette and proper behaviour, ghosts were an exotic glimpse behind a forbidden curtain.

Yet sometimes ghosts (or the idea of them) were a great source of education and entertainment.

And while they had their books, they obviously didn’t have horror films. But that doesn’t mean the thrillseekers of the age didn’t have any access to a more visual, up-close-and-personal ‘horror’ experience.

A New Phantasmagoria

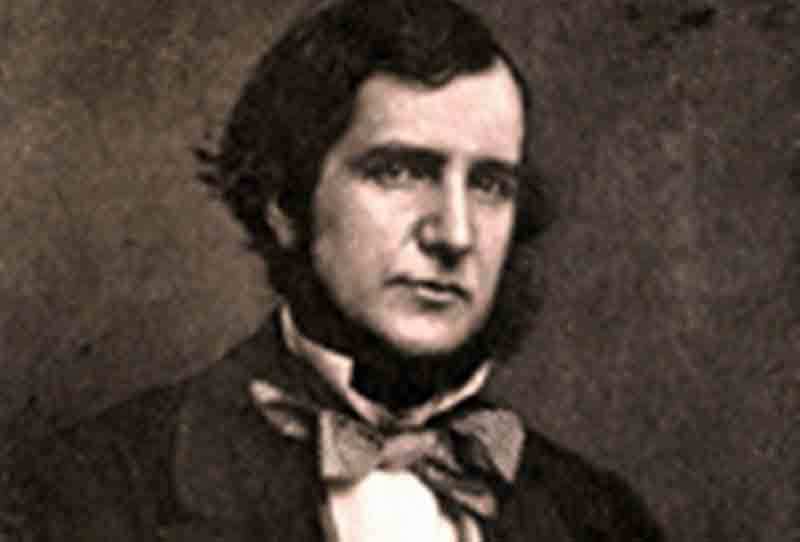

In 1862, Henry Dircks, a Liverpool-born engineer and inventor, developed a new take on the aged ‘phantasmagoria’ – a stage show based on projecting frightening images. Dircks’ version made it appear as though a ghost had actually appeared on stage.

While a fairly simple modification achieved using a hidden room, lighting trickery and the mirror-like qualities of plate glass, Dircks’ invention was too cumbersome for most theatres and so went nowhere until it was further developed by John Henry Pepper.

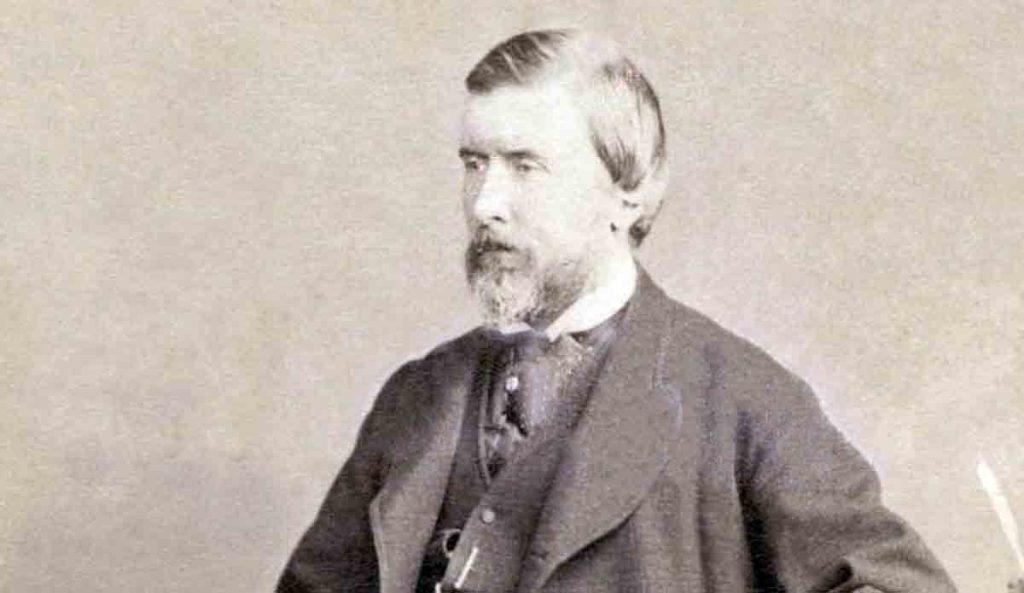

Who was Professor Pepper?

A celebrity on the scientific lecture circuit, Pepper was a Fellow of the Chemical Society and a teacher at the highly-respected Royal Polytechnic Institution in London.

His improvements made the whole thing far more manageable and after successfully debuting the technique during an 1862 staging of the Charles Dickens story, the Haunted Man, the two men took out a joint patent in early 1863.

Shortly afterwards, the ‘ghost’ went on tour all over the country in 1863 and ’64, being routinely advertised as ‘Pepper’s Ghost’. He retained the financial rights, too. Eventually, the two men predictably, quarrelled over the imbalance of credit and cash.

The show certainly pulled the crowds and as a special effects technique, it’s still used today on stage and in haunted house attractions. But how good was it? And was it scary?

It’s hard to say, but a lengthy review of Pepper’s Ghost at the town’s Corn Exchange in the 28th October 1863 edition of the Dundee Advertiser gives at least a flavour of the show, and the audience’s expectations.

Pepper’s Ghost Haunts Dundee

The show opened with a series of paintings depicting events in the then-ongoing American Civil War but this “part of the exhibition, though in itself splendid and worthy of a visit, excited but a secondary interest when brought into competition with the superior attractions of the ghosts.”

After a delay that “was unavoidable, and the expressions of impatience, therefore, quite uncalled for… the spirits from ‘the vasty deep’ appeared at last upon the scene, ‘large as life’ and with countenances wearing the cadaverous hues of death.”

Sounds good so far…

The Haunted Man

Our nameless reviewer describes the first of the ‘ghosts’ – yes, the public got more than one – as first appearing in scenes from Dickens’ Haunted Man. A chemist in his laboratory is visited by a ghost and “… a strong weirdlike light shines upon the ghost, [while] the chemist himself… walks in dim shadow, so that the impression produced upon the mind of the spectator is that the ghost is the more substantial of the two figures.”

The newspaper continues “the ghost is not a mere motionless statue, but… with all the faculties and attributes of a living and sentient human being, except that it cannot speak. It can… move the lips, the eyes, the head, the whole body, but all is dumb show.”

A Ghostly Bride

“The second spectre represents a bride in wedding costume, and so perfect is the illusion that you see though you cannot hear the rustling of her silk dress. Slowly she lifts the white veil from a face which would be handsome were it not so pale and death-like. You think you could grasp the figure, so real and substantial it seems…”

Another scene, set in a sculptor’s studio, works so well that “the illusion in the last scene is perhaps superior to that in the first, though in both it was very complete.”

“The exhibition is on the whole a very amusing one, and well deserved the cordial reception accorded to it last night by the multitudes who flocked to witness it.”