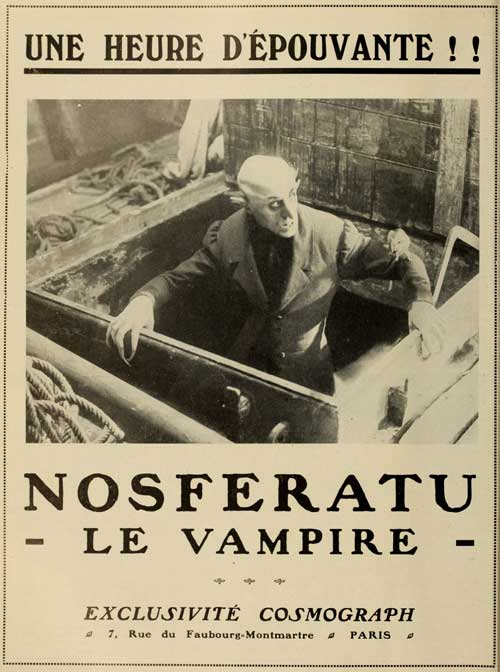

BARRY McCANN looks back on the grandaddy of all vampire films, the magnificent Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922)

TITLE: Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (translated as Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror, or simply Nosferatu)

DATE RELEASED: 1922

DIRECTOR: F.W. Murnau

CAST: Max Schreck, Gustav von Wangenheim, Greta Schröder, Alexander Granach, Ruth Landshoff, Wolfgang Heinz

One of the most iconic moments in Nosferatu is a sequence where the shadow of Count Orlok ascends the stairs and stretches out its hand to touch Ellen Hutter. This has become a metaphor for the film itself as, over the 93 years since it was made, Nosferatu has cast a large shadow over the vampire genre since. A shadow whose source very nearly became a privileged memory.

Having enjoyed a hit with his unauthorized 1920 Jekyll and Hyde derivative Der Janus Kopf, director F W Murnau turned his attention to Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Reputedly failing to come to terms with the novel’s publisher, Constable, he decided to forego the formality of obtaining the screen rights and quietly borrow Stoker’s plot, as he had with R L Stevenson. With some changes of character names and locations, Murnau was confident that Nosferatu would succeed as his own work.

The film opens in the German town of Wisborg with the newly wed Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) and Ellen (Greta Schroeder). Hutter’s employer, Knock, sends him to Transylvania to arrange for Graf Orlok (Max Schreck) to purchase a house across the street from where the Hutters live. Ignoring the warnings from locals en route, Hutter travels to Orlock’s castle and stays as guest to the sinister, cadaverous count. He is eventually bitten by the vampire, but spared death when Orlock senses Ellen. After witnessing Orlock depart the castle on a cart loaded with coffins, Hutter escapes and pursues him.

The schooner transporting the caskets is infested with rats and the crew become sick one by one until all but the captain and first mate are dead. When the first mate goes below to destroy the coffins, Orlok rises and the horrified sailor jumps into the sea. The captain is Orlok’s next victim.

When the ship arrives in Wisborg, Orlok leaves unobserved, carrying one of his coffins, and moves into his new abode. The town is then stricken with plague, resulting in many deaths.

Being opposite the Hutter’s home, Orlok becomes fixated with sleeping Ellen who he observes from his window. Aware of the vampire’s presence, Ellen has learnt that the way to defeat the creature is to distract him with her beauty until sunrise. But her first attempt to invite him in results in her fainting and Hutter goes to fetch Professor Bulwer, an expert on the Nosferatu.

In her husband’s absence, Orlok enters her chamber and the ruse works. As the rooster crows, Orlok attempts to flee but disintegrates into smoke. Ellen lives just long enough to say goodbye to the grief-stricken Hutter.

Nosferatu was made in post WW1 Germany, a time when the country was steeped in the ravages of war and being further bled by the winning allies through the payment of reparations.

Though shot mainly on location, its expressionist credentials are underlined by diagonally composed shots and extensive use of shadow. Murnau also added colour tint to enhance some moments, particularly dark blue to denote nigh time scenes as they were actually shot in daylight.

The acting is also stylised with a child-like Hutter and the simian Knock who manipulates him on the orders of Orlok, a physically exaggerated grotesque devoid of humanity.

He doubles both as a figure of tyranny in common with characters like Dr. Caligari and Dr. Mabuse, and as a pestilent human rat who brings a plague of death wherever he goes. Again, this may have run deep with Germans who felt their country diseased by the interference of foreign powers.

In “freely adapting” Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Murnau keeps the Transylvanian section fairly close to the novel, with only the vampire wives and wall crawling sequences absent.

Once the action moves to Wisborg, the film then becomes more its own creature. The cast is streamlined with no equivalents of Arthur, Quincy or Lucy, and Orlock kills his victims rather than turns them undead. And whereas sunlight merely weakened Dracula’s powers, Orlok becomes the first vampire to die by it. An innovation that has become part of modern vampire folklore ever since, most notably used to destroy Armand Tesla in 1943’s The Return of the Vampire, and Christopher Lee in the 1958 Dracula.

Despite these departures, Stoker’s widow, Florence, smelled a rat and began pursuing Murnau through the courts for compensation. When it became obvious there was none to spare, she ordered all copies of the film to be destroyed, including the negative. Fortunately, some prints escaped the cull, particularly one acquired by Universal for reference when first mooting their legitimate Dracula adaptation in 1928.

It was not until the 1960s, however, that Nosferatu began to resurface as a late night filler on television. However, this was an abridged version missing some thirty minutes of footage and taken from a second generation film print. Not only was the picture quality poor but missing the colour tinting, making the night scenes look ridiculous as they were now so obviously daytime.

A full length 90 minute print was eventually tracked down and made available during the 1980s. More recently, it has been restored with crisply sharpened picture quality, the re-introduction of multi tinting and the original orchestral score by Hans Erdmann, composed to accompany its original release. This edition is now available on Blu-Ray.

With the film’s centenary approaching, Nosferatu has diminished none of its power. It remains a compelling, poetic and authoritative essay of the uncanny. Or, as its subtitle declares, a symphony of terror.

Tell us what you think of Nosferatu 1922 in the comments section below!