Hammer’s Dracula received its UK premiere on 22 May 1958. To celebrate the 60th birthday of this British horror institution, RICHARD PHILLIPS-JONES unearths 13 interesting facts around its production and release…

With the massive success of The Curse Of Frankenstein, it would seem that a new take on Dracula would be a no-brainer for the company.

Curiously, however it was not the only vampire story on Hammer’s minds. An adaptation of Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend was also in the works, but would ultimately not go into production. (You can read more on this particular saga here)

Hammer had to be quick off the mark. Their success was already spawning rivals and imitators, with Tempean Films’ Blood Of The Vampire rushed into production, whilst the United Artists-produced The Return Of Dracula (1958, starring Francis Lederer in the lead) would actually beat Hammer’s film in reaching US theatres.

Despite their recent success, the company still had to shop around for a production partner.

A couple of tentative agreements fell through, perhaps due to possible legal issues relating to Universal’s residual rights in the property from their earlier agreement with Bram Stoker’s widow. However, once Universal themselves came on board (in return for distribution rights throughout most of the world), production commenced on November 11th 1957.

The Making of Dracula 1958

Made in six weeks, the production was budgeted at a very modest £81,000 (around £1,928,000 in 2018 prices).

Of this, Christopher Lee later said that his fee accounted for a mere £750, although it’s worth remembering that he only appears on screen for around seven minutes of the film, with thirteen lines of dialogue. Peter Cushing received top billing.

Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster conceded that it was necessary to heavily condense the core themes of the novel in order to accommodate the small budget. Hence, Dracula never sails to Whitby, Jonathan Harker becomes a vampire hunter who is quickly dealt with by the Count, and Renfield is nowhere to be seen.

Other characters have their storylines combined into one, whilst other elements are jettisoned completely. However, as Hammer alumni Freddie Francis later commented, “If an audience thinks about Jimmy’s script, then you’re dead, but Jimmy used to get them rattling along at such a pace that the audience didn’t have time to think about them”.

The shoot ran over a particularly cold winter, and conditions on the back lot and on location were freezingly uncomfortable. Several members of cast and crew would later recall that their saviour was the welcome hot lunches provided at the studio canteen.

The horse carriages used in the film were authentic period models from the collection of George Mossman, who took the reins himself for some scenes, although Peter Cushing insisted he should learn to handle the carriage himself for his own scenes. A fruitful association with Hammer would continue, with Mossman’s carriages appearing in all of the company’s Dracula films, right up to the prologue of Dracula A.D. 1972. They can now be seen at the Stockwood Discovery Centre in Luton.

As with his earlier take on Frankenstein, director Terence Fisher declined to view Universal’s previous film, not wanting to be influenced in his own take on the story. He eventually caught up with it on television some years later.

Fisher was at pains to emphasise Dracula’s sexual attraction and magnetism. In an interview with Alan Frank, he said: “It’s a physical thing, horror. The first time you see Dracula, up at the top of the staircase, in silhouette – and the audience, the ones you want to laugh, start to laugh because they think they’re going to see… what? Instead, they see this very handsome man, the perfect host come down the stairs, into close-up. I did it this way, not just to tease the audience but to show them that the whole idea of evil is very attractive. It’s one of the great cards that evil holds!”

Peter Cushing had a great hand in the film’s dramatic climax. In the script, Van Helsing simply brandishes a crucifix and forces Dracula into the sunlight, but Cushing felt something more dashing was called for. He came up with the idea that he should run along the tables and leap at the curtains, ripping them down and letting the sunshine into the room. The result was an iconic moment in film history.

In keeping with Hammer’s economical production system at Bray Studios, just three days after shooting was completed, Dracula’s sets were redressed so that production could begin on The Revenge Of Frankenstein (1958).

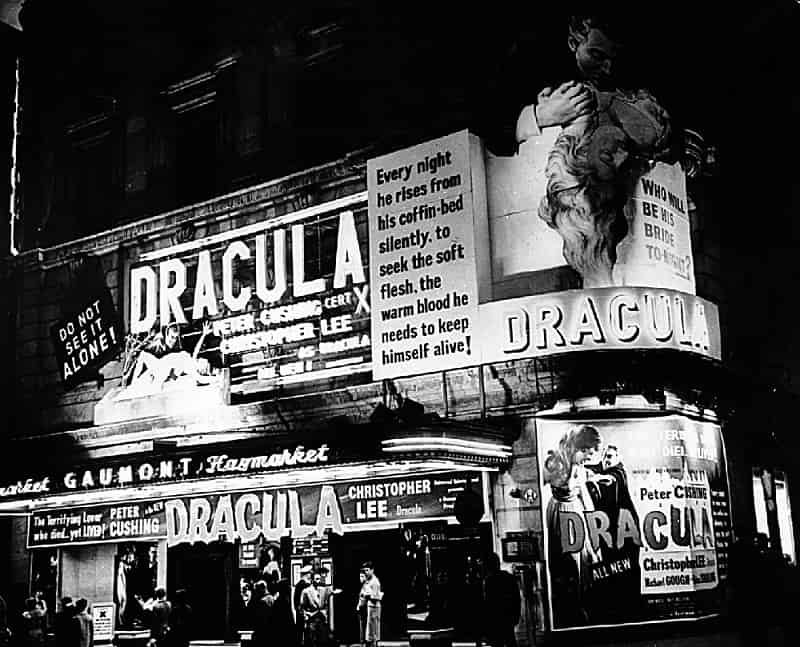

The film was retitled for the US market as Horror Of Dracula. Several theories on Universal’s decision have arisen over the years, but the most plausible is that their earlier 1931 Dracula was still popular on the re-release circuit, and the title change was simply to make it clear that this was an all-new feature. However, the film’s correct title is simply Dracula.

Universal’s then president Alfred Edward Gaff apparently greeted Lee, Cushing and Anthony Hinds at the company’s headquarters by exclaiming “I want you to know that your picture has saved Universal from bankruptcy!” Years later, Lee recalled that he asked both Cushing and Hinds afterwards if he had heard that correctly, and both confirmed this. Universal’s precarious financial situation at the time would certainly suggest that the film’s US success did much to put their accounts back in the black – it is said that the film eventually raked in over $25,000,000 globally. Based on the ratio of its original budget against total gross, it might still be considered the most profitable British film of all time.