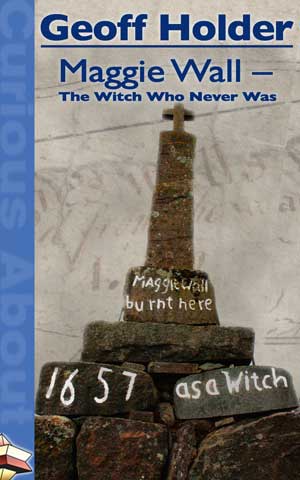

Author GEOFF HOLDER reveals how Perthshire has a monument to a witch, Maggie Wall, who never existed!

It is one of the most astonishing monuments in the British Isles, never mind Scotland.

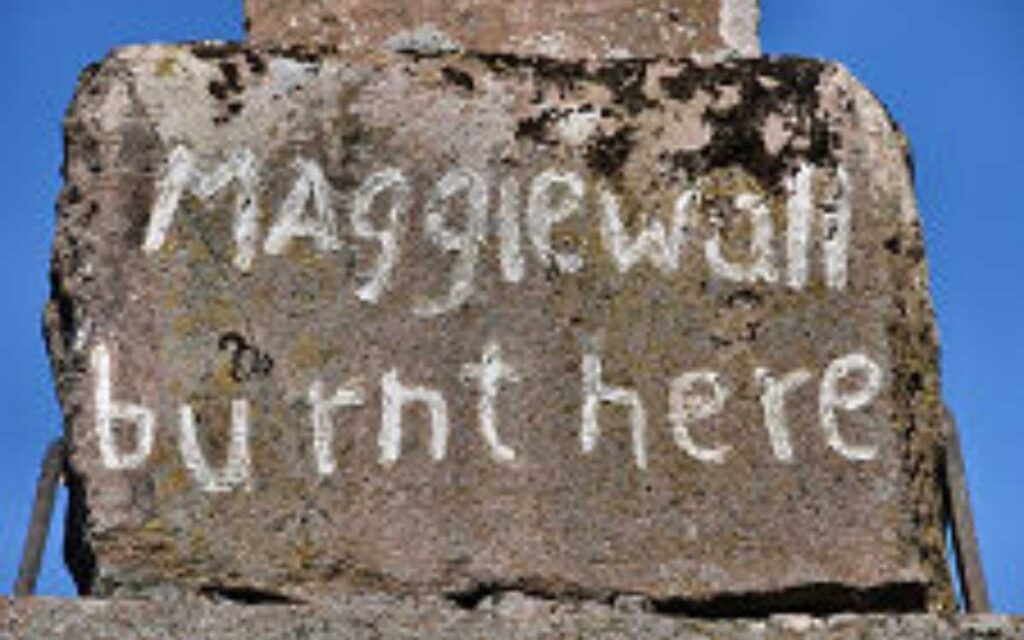

Deep in the Perthshire countryside in Dunning stands a cairn of boulders topped with a tall, spindly cross, the stones painted with the stark words:

Maggie Wall

burnt here

1657 as a Witch

There is nothing like it anywhere: a historic monument to a named witch.

There is, it is true, the occasional plaque here and there in Scotland to the events of the witch-killings of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; but these are modern remembrances, created out of modern sensibilities.

The Maggie Wall monument, by contrast, is old.

And it is mysterious. Questions abound. Who was Maggie Wall? What happened to her? Why, of all the hundreds of people executed for witchcraft, does she alone have a monument?

Why is there not a single mention of her in the witch trial reports, doubly strange given that we know the names of the eight women executed in Dunning in 1662? Why is there a cross on the top? Is the monument a sepulchre or a cenotaph? Who built it? When? And why?

The Maggie Wall Witchcraft Monument

The monument is Category B listed by Historic Scotland, meaning it is a “building of regional or more than local importance” on the government’s Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest, which grades buildings as A, B or C Listed, with A being the highest category.

It was inscribed on the list, and thus given legal protection, in 1971. The painted name, by the way, is Maggie Wall, not Maggie Walls: any number of modern iterations and websites tend to use the erroneous ‘Walls’ version.

‘Offerings’ and ‘Memorials’

If you visit the monument you may find various ‘offerings’ or remembrances deposited by some visitors. I have seen the following: Coins. Flowers. Candles, usually tea-lights. Shells. Horseshoes. Carved pumpkins. Party decorations.

Halloween toys such as small plastic pumpkins or witch figures.

Small teddy bears and other soft animal toys.

Fairy figurines.

Presumably these are left by contemporary witches and neo-pagans, or by children captivated by the fairy-tale ambiance of a real-life witchcraft location. It should be pointed out that everything left at the monument is actually ‘ritual litter’, with the emphasis on ‘litter’.

Local people get a bit fed up with clearing the place up. If you go there, please do not leave anything behind.

The Ugly Truth

Both locals and visitors tend to assume that Maggie Wall was a real person – why else, they ask, would there be a monument to her?

The truth, however, is far stranger.

The archaeology of the structure’s stonework suggests a very late eighteenth-century or very early nineteenth-century date, long after the witchcraft era ended.

And the original estate maps and factor’s books of the era show that in 1755 the site where the monument now stands was a walled field named Maggie’s walls. Which is to say, the walled field of Maggie.

And if you might be tempted to think that at the very least there must have been a woman named Maggie, you are to be disappointed there as well: several eighteenth-century written records refer to the field as Muggies Walls. ‘Muggie’ is an obscure word, but it may be related to Mugg and Mugg-ewe – “a sheep with a good coat of wool”.

This is the discomforting truth: Maggie Wall is not the name of a person. It is a placename.

Maggie Wall the witch never existed.

Who Built The Monument?

I can’t prove it – because the records are incomplete – but I contend that the monument was constructed by the local schoolteacher and building developer, who was the tenant of Muggies Walls from 1797 to at least 1802.

He had the access, he had the materials, he had the means, and he had the opportunity.

But what was his motive?

Why did he spend so much money and effort in constructing this bizarre structure?

And why did he name it after the field in which it was built?

Well, that at least still remains a mystery.