The Peer, the Harbour, and the Zoo? TREVOR BOND looks at several weird theories surrounded the fate of 1970s fugitive murderer Lord Lucan

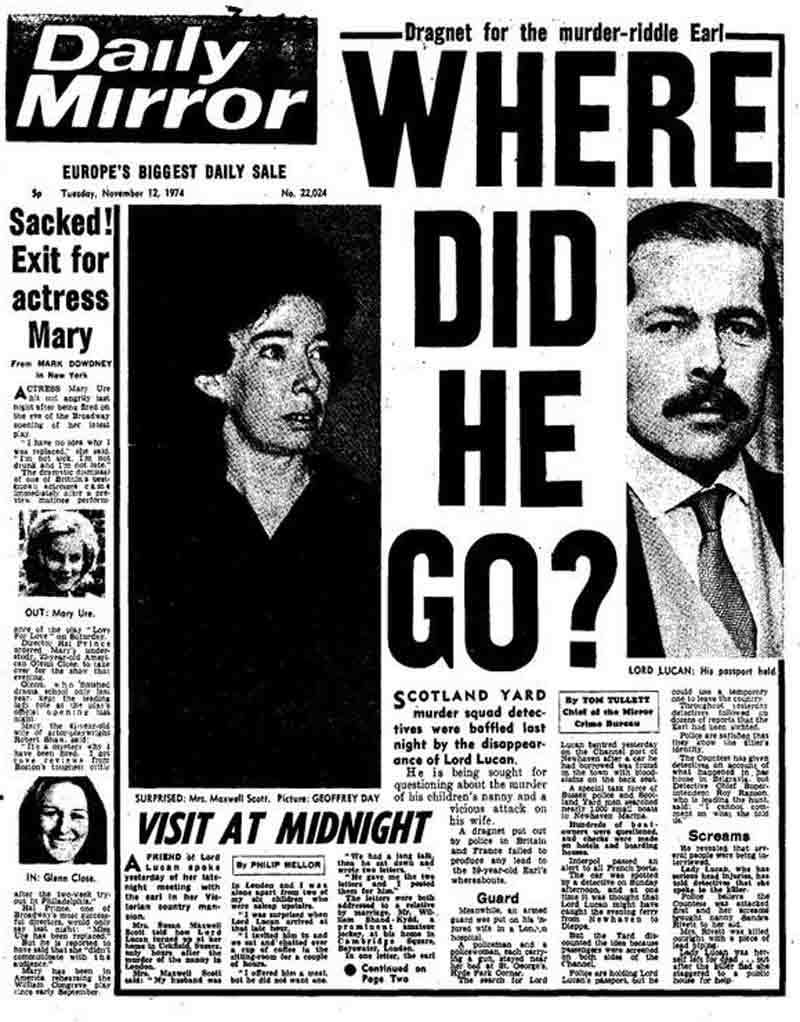

In the summer of 1975 the inquest into the death of 29-year-old Sandra Rivett concluded with a verdict of murder.

Rivett, who worked as a nanny, had been bludgeoned to death on 7 November of the previous year, in the basement of 46 Lower Belgrave Street, Belgravia in London.

Her employer, Lady Veronica Lucan, was also subsequently attacked, but had managed to escape – battered and bloodied – to a nearby pub, where she raised the alarm.

Lady Lucan was never in any doubt about the attacker, and in 1975 neither was the Coroner, who unequivocally named the culprit as Veronica’s estranged husband Richard Bingham – peer of the realm, speedboat enthusiast, professional gambler, former soldier, and one-time candidate for the role of James Bond.

Who was Lord Lucan?

Bingham – better known by the public by his hereditary title of Lord Lucan, and by his gambling associates at the exclusive Clermont Club as ‘Lucky Lucan’ (ironically so, given his crippling debts by the time of the attacks) was now also considered a murderer.

There was to be no trial, however. After writing a brace of letters, making a number of phone calls, and driving to a friend’s home in Sussex, Lucan had not been seen since the early hours of 8 November 1974. Two days later the car which he had been driving that night was discovered near Newhaven ferry port, a piece of lead piping contained within.

Ever since, the question of ‘what happened to Lord Lucan’ has become one of British history’s most enduring mysteries. But what really did become of ‘Lucky Lucan’?

Let’s take a look at some of the theories…

Lord Lucan was hidden in Kenya

Shirley Robey, who began working as a secretary for Clermont Club owner John Aspinall five years after Lucan’s disappearance, claimed much later (in 2012, initially under the alias of Jill Findlay) that she had overheard conversations between her employer and another club regular, James Goldsmith, which implied that Lucan was still alive and that Aspinall remained in touch with him.

Soon after, according to Robey, she was asked to make arrangements for Lucan’s eldest children to travel to Gabon, and from thence to Kenya. Robey’s assumption, at least in hindsight, was that the intention was for the children to be seen by their father, with or without their knowledge.

Allegations regaring the complicity of Aspinall and Goldsmith in Lucan’s fate were not new when Robey voiced them. In 1976, James Goldsmith had become so incensed with suggestions in ‘Private Eye’ magazine regarding the pair undertaking secret meetings to discuss the case that he attempted to sue for libel. His complaint, bundled in with other grievances against the magazine and its distributors, was eventually settled out of court – according to a lawyer acting for ‘Private Eye’ at the time, on favourable terms for the publication.

A Brother’s Secret

An alternative African link involves another member of the Bingham family – Lucan’s younger brother, Hugh, who in 2016 told reporters that his brother had ‘no option but to flee’ following events in Lower Belgrave Street.

Hugh Bingham died in 2018 in his long-term hometown of Johannesburg, South Africa. Three months later, various newspapers began reporting that Hugh had been working on a book which may have shed light on events. Whist the book remains unpublished, a journalist who claimed to be familiar with the contents claimed that Hugh’s theory had been that Lucan had fled for a new life in South Africa, living six hundred miles from Johannesburg.

Two brief flurries of media attention earlier in the same decade may also be of interest in relation to Hugh’s alleged solution – firstly, reports in 2011 of Lucan’s son, George (today the 8th Earl Lucan) had spent an extended holiday in Namibia, neighbouring South Africa, where one of his hosts ungenerously described him as a uniquely peculiar character and seemed to have objected particularly strongly to his fondness for midnight walks.

The next year, in February, reports spread of a watch allegedly engraved to Lucan from friends at the Clermont Club which had been discovered in a shop in South Africa. Although photographs were distributed, the watch was withdrawn without explanation from a planned auction the following month, and so to date the item, the engraving, and its provenance remain yet to undergo clear scrutiny.

‘Bumped Off’

Whether it is PD James and the Ratcliff Highway Murders or Patricia Cornwell and the mystery of ‘Jack the Ripper’, from time to time crime fiction authors cannot help getting involved in the world of true crime.

In 2016, Peter James, author of ‘The Perfect Murder‘ amongst many others, followed suit by telling a literary festival crowd that he was certain that Aspinall and others had secreted Lucan in a hideaway near Montreaux in Switzerland following Sandra’s murder and the attack on Veronica.

Here, however, events took a turn for the worse – at least, according to James and his unnamed sources. Supposedly due to his desperation to contact his children, Lucan became a liability to his friends, who arranged in James’ words to have him ‘bumped off…Mafia style’. Whatever the truth of the theory, it is certainly a good ending – in fact precisely the kind of twist of which an award winning fiction author would be proud.

Dead in the Harbour

In 2000, just months before his own death, John Aspinall told reporters of his belief that Lucan commited suicide at Newhaven – likely even before the discovery of his car – by heading out into the harbour on a speedboat before deliberately sinking the vessel, having also tied a stone around his own neck. Another member of the Clermont Club crowd, James Wilson, later made broadly similar claims in 2015 although, as was also the case with Aspinall, he gave little evidence for his certainty besides his own assessment of his friend’s character.

A peculiar article published in ‘The Guardian’ following Aspinall’s death cast some doubt on this theory, as the writer believed they had caught Aspinall making an unguarded remark which suggested Lucan was indeed still alive during one of his final interviews. Given that the same journalist revealed they believed Aspinall, who also owned Howlett’s Zoo, had suffered a concussion after being kicked by a herd of elephants prior to their conversation, such semantic analysis should perhaps be treated with caution.

Other proponents of suicide theories have also favoured a watery grave, whether accessed through commandeering a private vessel or jumping from a ferry out of Newhaven. George Bingham, who as a child had slept through the attacks on his nanny and mother, told in 2012 of his belief that his father had sailed into the harbour before taking a lethal combination of alcohol and prescription drugs and then deliberately sinking his vessel before falling unconscious. Curiously, he also stated that he felt Lucan would only have done so if he bore some guilt for events.

The most steadfast believer in a suicide scenario was undoubtedly Lady Veronica Lucan herself, who maintained such a belief for decades up to her own death in 2017. In her memoir ‘A Moment in Time‘, she posited enigmatically that her husband may have been assisted in this by his in-depth knowledge of boat propellers.

Disposal at the Zoo

In 2016, shortly before the High Court finally ruled that Lucan should be legally ‘presumed dead’, another former Clermont Club gambler surfaced with the most incredible suicide theory yet. Philippe Marq claimed to know, via yet another fellow gambler named Stephen Rafael – that rather than heading to the English Channel, Lucan had instead travelled to Aspinall’s zoo near Canterbury. Here, according to Marq, the peer shot himself, before Aspinall and other conspirators performed one final favour for their friend – disposing of his body by feeding it to a tiger.

Red Herrings

Back in the 1960s, when Richard Bingham was meeting and marrying Veronica Duncan and acquiring his father’s title, John Stonehouse – the son of a trade unionist – was a Member of Parliament, a rising star of the Labour Party, and a Communist Spy. The two men could not have had much less in common but an extraordinary coincidence was to see their stories intersect during the coming decade.

By the early 1970s, Stonehouse found himself on the verge of financial ruin due to rumour, political disagreements, and failed and increasingly fraudulently managed businesses. And so, the MP hatched a plot. Unknown to his wife (but not to his mistress) Stonehouse faked his own death on a Florida beach and set off for a new life in Australia, living under the name of a deceased constituent. It almost worked – the authorities had been fooled, and no one was searching for John Stonehouse. They were, however, very much searching for Lord Lucan, who unfortunately for Stonehouse’s plans, had disappeared just twelve days before his own vanishing act.

In such context, the mysterious Englishman who had recently arrived down under immediately attracted attention. Initially suspecting that they had located Lucan (despite the missing peer being nine years his junior), Australian police questioned Stonehouse and soon realised his true identity. He was arrested on Christmas Eve 1974, and eventually spent three years in prison. The hunt for Lord Lucan would have to continue.

Twenty-nine years later, the Sunday Telegraph serialised extracts from the book ‘Dead Lucky’, written by former Metropolitan Police officer Duncan McLaughlin, claiming in no uncertain terms that the Lucan enigma was solved. Unfortunately for McLaughlin the person whose photograph adorned the cover of his book, identified as the missing man whilst living in Goa by a former drug dealer, was in fact a former folk musician from Merseyside named Barry Halpin. Friends of Halpin, who had died by the time McLaughlin’s book was published, even contacted newspapers to say the author had mistaken his nickname – not ‘Jungle Barry’, as was claimed, but instead ‘Mountain Barry’.

More recently, in 2007 a photographer from North London who had moved to New Zealand in 1974 following a bereavement was identified as a potential Lord Lucan by a neighbour whilst living a simple life between his one-acre property, shed, and car with his pet cat, goat, and possum. A retired Scotland-Yard detective was able to confirm the man’s claim that his identity was that of one Roger Woodgate – ten years too young to be Lucan and reportedly lacking almost half a foot in height. Nothing has been heard of Woodgate since, who said at the time that he was considering moving to Peru.

And finally… Terminated!

Inevitably, Lucan’s disappearance has also birthed some ludicrous theories (that is, if betrayals in the shadow of Lake Geneva and the innovative use of a hungry big cat are not ludicrous enough already). A personal favourite owes its genesis to an English-educated Italian businessman named Giovanni Di Stefano, a self-described lawyer who styled himself as the ‘Devil’s Advocate’. In Di Stefano’s version of the Lucan story, the missing man was murdered by none other than Arnold Schwarzenegger, then a 27-year-old ‘Mr Olympia’ and recent star of ‘Hercules in New York’.

The theory goes that the future Terminator was under instructions from Lucan to murder his wife, but that the actor and bodybuilder subsequently murdered his erstwhile employer in order to avoid the blame for mistakenly murdering the nanny instead, and allowing his intended victim to escape.

In 2013, Di Stefano was sentenced to 14 years imprisonment for fraud and deception after it was discovered that he had no legal qualifications. In his defence, Di Stefano stated that he had been awarded such qualifications by his close friend, former Serbian president Slobadan Milošević. For some reason, his Lord Lucan theory never gained widespread publicity.

In 2016, the possibility of a hitman’s involvement was also raised by Neil Berriman, the son of Sandra Rivett, who claimed to have seen police records which proved not only that Lucan had survived after 1974 but that his mother’s death (and by extension also the attack on Lady Lucan) had been carried out by a hired killer, although not necessarily an Austrian action star. Despite being challenged to produce evidence of his assertions, which also featured implications of police corruption, Berriman is yet to do so.

Discover other shocking murders from London here.