TREVOR BOND reveals the most gruesome killings ever committed in London, and how the public reacted!

Capital, financial centre, seat of power – London is never far from the headlines. Over the centuries, though, it has also been the backdrop for a number of brutal, and fascinating, crimes.

Roll up, roll up, for a run through ‘the 10 shocking brutal murders that shocked London’.

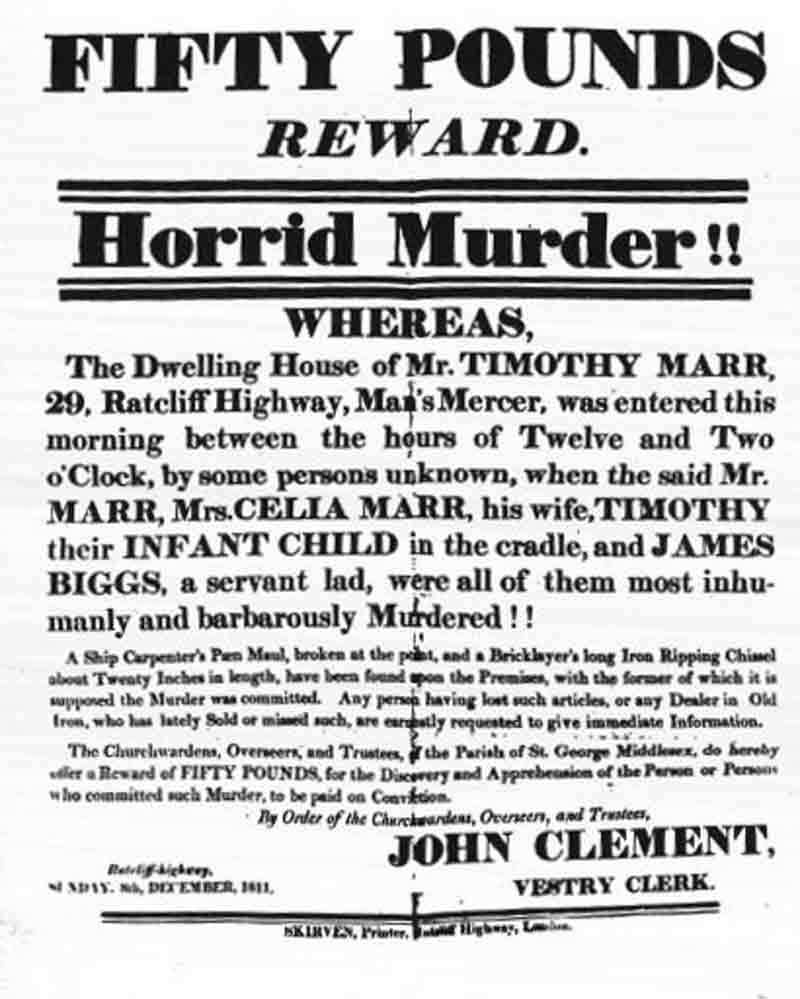

1. The Ratcliffe Highway Murders

Seventy-seven years before the ‘Jack the Ripper‘ crimes, the East End of London was transfixed with news of another brutal series of crimes- the so-called ‘Ratcliff Highway Murders’, in modern-day Stepney.

On 7 December 1811, just before midnight, hosier Timothy Marr sent a servant, Margaret Jewell, on an errand to buy oysters.

When she returned (having failed in her mission) she found the doors locked.

Once assistance was summoned, a terrible scene was discovered. Marr, his wife Celia, and apprentice James Gowan had been battered to death.

The Marrs’ 14-week-old son still lay in his crib, with his throat cut.

Twelve days later, three more victims were added – publican John Williamson, his wife Elizabeth, and their servant Bridget Harrison, murdered at the Williamsons’ public house, the King’s Arms.

Who did it?

The authorities strongly suspected a sailor named John Williams, who was supposed to have known Timothy Marr.

Williams was arrested, however, he committed suicide in prison whilst awaiting trial.

This did not dissuade the powers-that-be from parading Williams’ corpse through the streets and burying him at a crossroads (intended to confuse any returning spirits), covered in quicklime and with a wooden stake through his heart.

Can I visit the crime scenes?

In a fashion, although the Ratcliffe Highway (now simply named The Highway) has changed a lot since 1811.

The site of the Marrs’ business would have been just west of the junction with Artichoke Hill, on the northern side of the road, whilst the Kings Arms would have stood on modern-day Garnet Street, heading towards Wapping.

The crossroads where Cannon Street Road and Cable Street meet, and where John Williams was buried, still exists though – in the shadow of St George in the East church, within the grounds of which the Marr family were buried.

If you want to get a sense of the feel of the time, Puma Court off Commercial Street was used to film scenes relating to the first set of murders for the third series of the ITV series ‘Whitechapel’, broadcast in 2012, and has changed little since the 19th century.

You can read more about The Ratcliffe Highway Murders here.

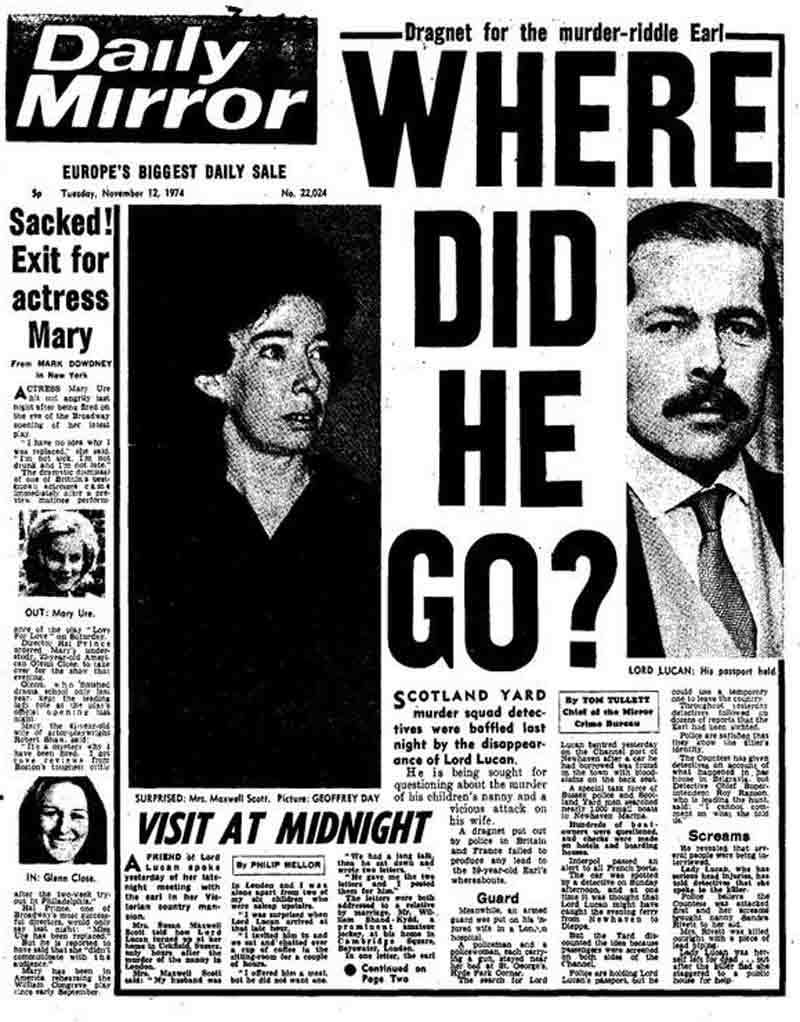

2. Lord Lucan and the murder of Sandra Rivett

Ask any Londoner of a certain age to name a famous missing person, and you will receive the same answer – Lord Lucan.

On 7 November 1974, an intruder broke into 46 Belgrave Street, Belgravia, and beat Sandra Rivett to death with a lead pipe.

Rivett was the nanny to the three children of her mistress, Veronica Lucan -better known as Lady Lucan, the wife of Richard John Bingham, the seventh Earl Lucan.

The couple had separated, acrimoniously, the previous year.

On that fateful night, Lady Lucan was the next to be attacked – although she escaped, and was able to flee to a nearby public house, the Plumber’s Arms.

The assailant, according to her, was not in doubt – her estranged husband, Lord Lucan.

You can read about Lord Lucan’s disappearance here.

Who did it?

Lady Veronica Lucan remained steadfast regarding her husband’s guilt until her own death in 2017, even to the detriment of the relationship with her own children.

The more intriguing mystery, perhaps, is what became of the Lord – over the decades since, theories have ranged from suicide to living in hiding in South America, Asia, Africa, and beyond.

Can I visit the crime scene?

Indeed you can, at least from the outside. 46 Lower Belgrave Street still stands, and is easily distinguishable not only from the number but as the only nearby house without columns flanking the entrance.

The Plumber’s Arms also remains, just a short walk along the street, towards Victoria station.

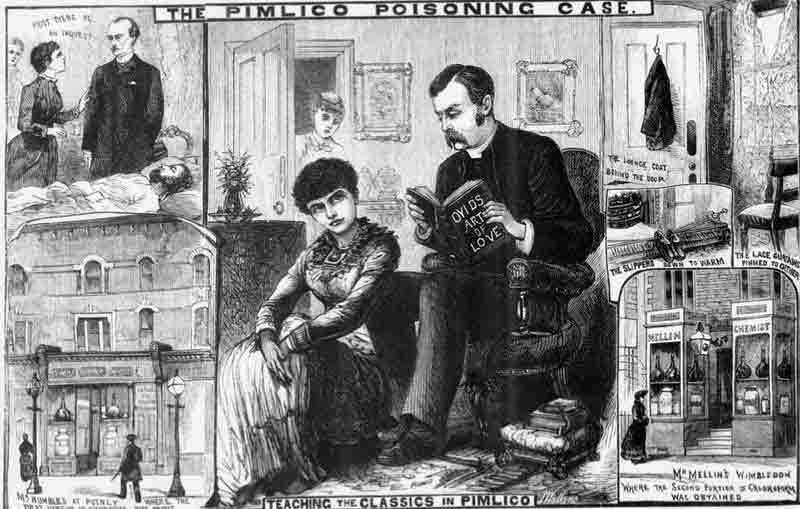

3. The Pimlico Mystery

In the early hours of New Year’s Day, 1886, 41-year-old grocer Thomas Bartlett was found dead in his home in Pimlico.

The subsequent investigation, championed by his father, would expose an unconventional relationship that shocked Victorian society.

The previous year, Bartlett’s wife Adelaide had met a man named George Dyson, the son of a Methodist minister and himself a man of the cloth.

Their relationship soon overstepped the boundaries of churchman and parishioner, allegedly with Thomas’ agreement and even encouragement.

It was the Reverend Dyson who purchased four bottles of chloroform prior to Thomas’ death, the very same substance which was found present in the stomach of his paramour’s husband’s stomach.

Who did it?

The police were in no doubt, and both Adelaide Bartlett and George Dyson were brought to trial in April 1886.

The prosecution, however, made a costly mistake.

They offered no evidence against Dyson, and Adelaide’s defence counsel was able to argue, amongst other things, that the case against her was no less circumstantial.

Her acquittal was reportedly greeted with approval, although Sir James Paget disagreed and famously declared that ‘now that she has been acquitted… she should tell us in the interest of science how she did it’.

Can I visit the crime scene?

Yes, although the odd-numbered side of Claverton Street, situated a short walk from Pimlico station, has since been replaced with an uninspiring series of post-war blocks of flats.

If you want to venture further, however, the church where George Dyson’s father once preached still stands in Llanelli, West Wales!

4. The Houndsditch Murders

In December 1910, an attempted robbery in the City of London led to dramatic scenes, tragedy, and eventually to significant changes in British policing.

Late in the evening of 16 December, Police Constable Walter Piper knocked on the door of 11 Exchange Buildings, off Houndsditch.

A nearby shopkeeper, Max Weil had alerted him to suspicious noises – but the heavily armed gang within did not have designs of Weil’s property.

Rather, they were breaking through into an adjacent jeweller’s shop.

Alerted by Constable Piper’s visit to the fact that they had aroused suspicion, those inside number 11 readied their weapons.

When further officers arrived, unarmed, they didn’t stand a chance.

Five officers were shot. Two of them, Sergeant Charles Tucker and Sergeant Robert Bentley died at the scene.

Another, Constable Walter Choate, died of his wounds the next day.

Who did it?

The gang was identified as a group of Latvian revolutionaries who had also been responsible for the deaths of another policeman and a 10-year-old boy following a bungled robbery in Tottenham the previous year.

The story finally came to an end two and a half weeks later when the police located remaining members of the gang hiding out in a house in Sidney Street, but not before a firefight lasting seven hours which has also become notorious – ‘the siege of Sidney Street’.

Can I visit the crime scene?

Exchange Buildings no longer exists, but standing at the junction of Houndsditch and Cutler Street you can still estimate its position.

You will also see a memorial plaque dedicated to Sergeant Tucker, Sergeant Bentley, and Constable Choate.

Controversially, in 2008 two tower blocks in Sidney Street were named ‘Peter House’ and ‘Painter House’ in reference to the alleged leader of the gang, known as Peter the Painter.

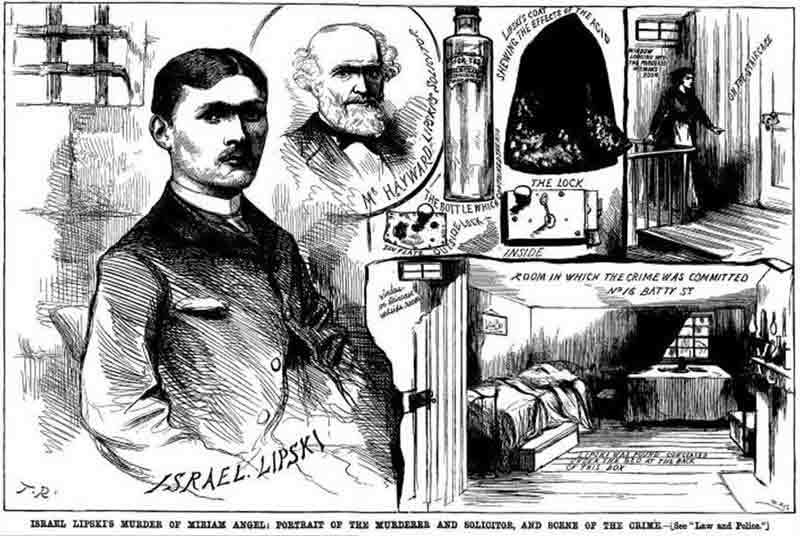

5. Israel Lipski and the murder of Miriam Angel

The East End of London has always been a hotspot for immigration.

This has included French Protestants escaping persecution, Irish residents forced abroad by the potato famine, and Eastern European Jews fleeing pogroms to Bengalis in the late 20th century.

In 1887, one murder threw light on the social tensions of such an environment.

On 28 June, Dinah Angel arrived at 16 Batty Street, Whitechapel, looking for her daughter-in-law Miriam who had failed to uphold an appointment to meet.

For a time, Miriam was nowhere to be found – until, that is, Dinah peered through a window near the staircase into Miriam’s locked bedroom.

Miriam Angel lay on her bed, semi-naked.

What little clothing she was wearing was stained with curious marks, and a foam-like substance was to be found around her mouth.

A post-mortem would reveal that she had been poisoned with nitric acid.

Who did it?

The police did not have to look far for their suspect – Israel Lipski, Miriam’s upstairs neighbour and a fellow Polish Jew.

He too had swallowed acid, but not in a fatal quantity.

The police felt that this was an attempt to divert suspicion, and despite Lipski’s protestations that he too had been a victim of the same attack in which Miriam died, he was arrested.

Journalist W. T. Stead mounted an impassioned campaign arguing Lipski’s innocence, suggesting that the accused man was the victim of anti-semitic prejudice.

Nevertheless, on 21 August, Israel Lipski was hanged at Newgate Prison.

By the following year, ‘Lipski’ had supposedly become a popular anti-semitic insult in the area.

Can I visit the crime scene?

You can. Although much of Batty Street – which can be found just south of Commercial Road – has changed, number 16 has remained.

And in an added extra for the student of East End crime, it stands next to an adjoining house which bears the famous year of 1888 above its door.

6. Thomas Briggs, Britain’s first railway murder

Fenchurch Street station opened in 1841, the first railway station to be built within the borders of the City of London.

The Victorian boom in rail travel revolutionised the transport of persons and goods across the country, but nevertheless, many people were concerned about the potential for crime on the lines.

Still, it was to take 23 years before Britain saw its first ‘railway murder’ – and it all began on 9 July 1864 with the 21.50 from Fenchurch Street.

Onboard was an elderly banker named Thomas Briggs, but when the train pulled into Hackney station he was nowhere to be seen.

What was found in a first-class carriage, however, was a quantity of blood, a stick, a hat, and a bag.

Two clerks alerted a member of station staff, and the carriage was locked as the train continued towards Camden.

Soon after, Thomas Briggs was discovered close to the nearby tracks.

He was still alive, albeit barely so, and was taken to a pub for treatment and from there back to his home.

Seemingly beaten with a blunt instrument before being thrown from the carriage, he died the next day.

Who did it?

Investigations led to the identification of a German tailor named Franz Muller, who had attempted to pawn a gold watch chain belonging to Briggs.

Muller was arrested, but not before a dramatic chase across the Atlantic, with suspect onboard one ship sailing for America and the police onboard another.

After maintaining his innocence throughout his trial, Muller reportedly confessed on the scaffold prior to his execution on 14 November.

Can I visit the crime scene?

The literal crime scene – the train carriage – is lost in the mists of time.

However, Fenchurch Street station remains and the site of Hackney station was only a short distance from the modern-day Hackney Central station.

The embankment where Briggs was discovered was close to where the A12 road now runs, as it crosses the Hertford Union Canal.

The pub to which he was taken, the Top O’ the Morning’, at 129 Cadogan Terrace, survived for many years but has now been demolished.

7. Minnie Bonati Trunk Murder

Sixty-three years after the murder of Thomas Briggs, a railway station again played a part in a sensational murder.

The staff at the Charing Cross Left Luggage department may have thought twice about accepting packages after the truth was discovered about one they accepted on Friday, 6 May 1927.

By Monday, it was starting to smell.

When opened, it revealed a shocking secret – inside, mixed amongst a selection of clothes and wrapped inside brown paper, were the portions of a woman’s body.

The body was eventually identified as that of 36-year-old Minnie Bonati, the estranged wife of an Italian waiter.

Who did it?

By his own admission, the culprit was a man named John Robinson, also revealed as a bigamist during the course of the investigation.

His only argument was that he had not intended to kill Bonati but had instead panicked when she attempted to rob him.

And after knocking her unconscious he had no choice but to cut up and dispose of her body.

He was hanged at Pentonville Prison on 12 August 1927.

Can I visit the crime scene?

Charing Cross and Victoria stations still remain, and the former still offers a Left Luggage service although responsibility for any dismembered corpses found within has been outsourced.

The site of John Robinson’s office at 86 Rochester Row, roughly at equal distances between Victoria and Pimlico stations, is now occupied by a more modern block.

8. Carlo Ferrari and the London Burkers

Today, Covent Garden is a popular destination for tourists in the market for expensive gifts, as well as a famous spot for street performers.

Prior to 1974, however, it was a thriving fruit and vegetable market, albeit one with a seedy side.

In 1831, the abduction from the market and subsequent murder of a 14-year-old trinket seller revulsed the nation.

On 5 November, a group of men attempted to sell a body to the anatomy school at King’s College.

Although this may seem bizarre, not to mention macabre, today it was at the time a common practice and one to which the authorities often turned a blind eye.

The rise of medical schools had created a demand for specimens, and the legal supply of executed criminals (the only bodies permitted to be used for the purpose) could not keep pace.

This body, for which a price of 12 guineas was being demanded, was different though.

In the words of a King’s College surgeon, it was ‘suspiciously fresh’.

It would transpire that the body was that of Italian immigrant Carlo Ferrari, enticed from his usual sales spot in Covent Garden, taken to a hovel in Nova Scotia Gardens, Bethnal Green, and murdered for profit.

Who did it?

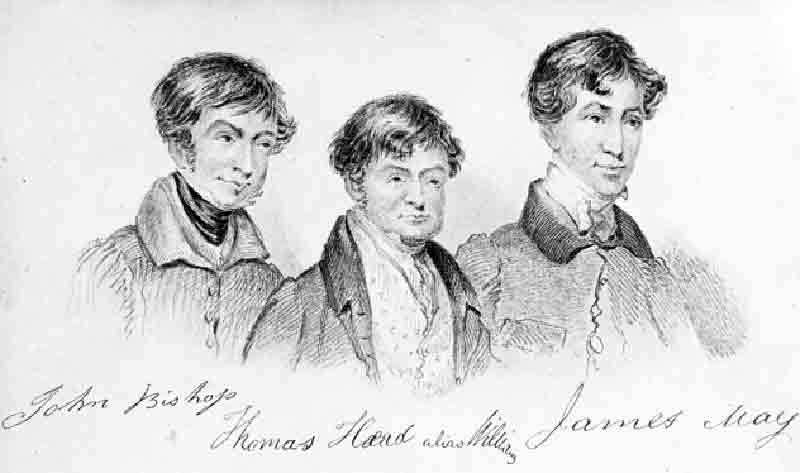

The group – John Bishop, Thomas Williams, and James May – were arrested at King’s College, and tried at the Old Bailey the following month.

All were found guilty and sentenced to death, although in the event May’s punishment was converted to transportation to modern-day Tasmania.

Bishop and Williams also confessed to a string of additional crimes, whilst a Covent Garden porter, Michael Shields, was allowed to remain at liberty, based on the testimony of his co-conspirators that he had only been involved in deliveries, not murder.

Today, Bishop, Williams, and May are remembered as ‘the London Burkers’, in reference to the similar crimes of Burke and Hare in Scotland in 1828.

Can I visit the crime scene?

Nova Scotia Gardens is long gone, and probably for the best, although the site of the houses roughly equates to modern-day Ravenscroft Park, off Colombia Road.

The Birdcage pub, frequented by the gang, still stands within sight of the park.

9. The Whitehall Mystery and The Thames Torso Murders

In October 1888, the Metropolitan Police were preoccupied with the murders of ‘Jack the Ripper’ in Whitechapel, But they were also eagerly awaiting the completion of a newly built headquarters in Westminster, known as New Scotland Yard.

Surely nothing untoward would happen there, though?

On 2 October 1888, within the New Scotland Yard building site, a shocking discovery was made, that of a headless, limbless torso of a woman.

The remains were matched to an arm fished from the Thames at Pimlico exactly three weeks earlier, and presumably much to the police’s embarrassment, also to a leg discovered elsewhere on the premises, not by the authorities but by the pet dog of a journalist.

Who did it?

We will never know.

The identities of the victim and the perpetrator were never discovered.

The crime has been tentatively linked to a series of similar murders known as ‘The Thames Torso Murders’ lasting from 1887 to 1889 and which saw body parts discovered from Battersea in the west to Essex in the east.

Can I visit the crime scene?

You can.

New Scotland Yard can still be found close to Westminster station, the best view of the Victorian buildings being from Derby Gate.

The Metropolitan Police moved back to the site in 2016, after significant building work – so expect a security presence!

10. Jack the Ripper

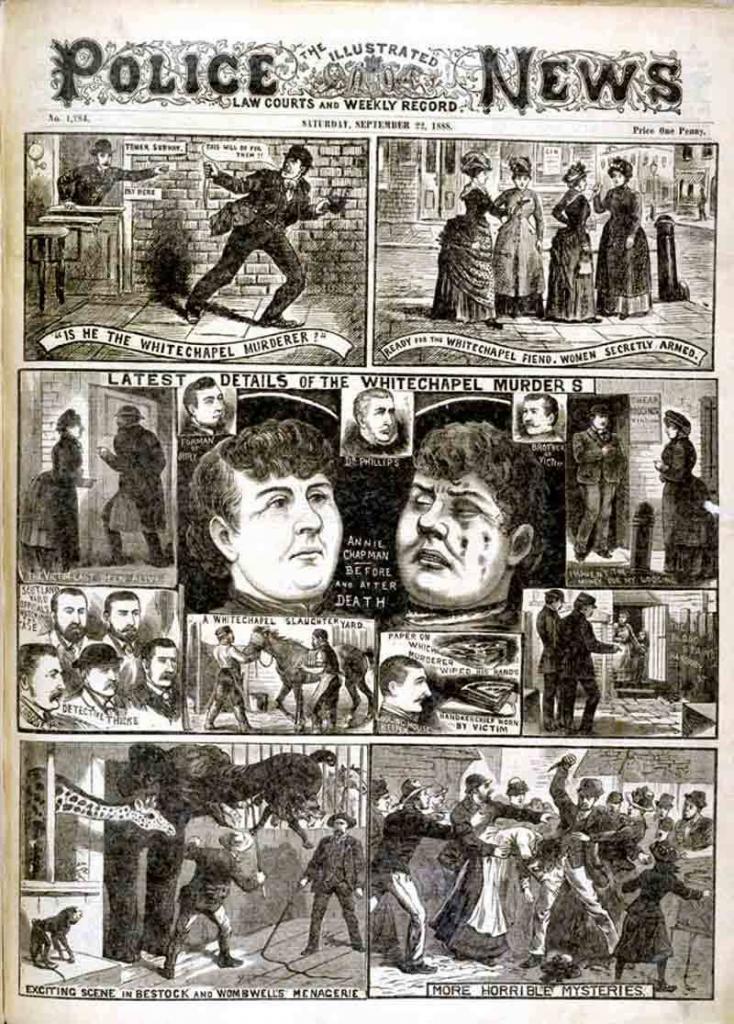

Between April 1888 and February 1891, 11 murders of women committed in and around Whitechapel were collected within what has become known as the ‘Whitechapel Murder File’.

However, it was five of those murders, taking place within a 10 week period, which most of the investigating officers and most experts today believe were committed by the same man.

This man is an enigma who, thanks to a letter that he may or may not have even written, has passed into infamy as ‘Jack the Ripper’.

The exact details of the deaths of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Kelly may vary, but the brutality of the attacks is undoubted.

Who did it?

The crimes remain unsolved, although during the 131 years since many hundreds of suspects have been proposed – ranging from Liverpool cotton merchant James Maybrick to Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor.

Can I visit the crime scenes?

Indeed. ‘Ripper’ tours are big business.

Today, most visit the sites (or close by) of the murders of Annie Chapman, in Hanbury Street, Catherine Eddowes, in Mitre Square, and Mary Kelly, off Crispin Street. Some also include an earlier potential victim, Martha Tabram, killed in modern-day Gunthorpe Street.

Less visited are the sites of the murders of Mary Ann Nichols, in Bucks Row (now Durward Street) and Elizabeth Stride in a yard off Berner Street (now Henriques Street).

Read more here with 13 Jack the Ripper locations the tour guides won’t show you!

About Trevor Bond

TREVOR BOND was born in South London to an East End family. He has a long-held fascination with the social and criminal history of London, with a particular interest in the Victorian period.

He has spoken at internationally attended conferences and events on subjects ranging from ‘Jack the Ripper’ to arsenic poisoning, and in 2016 he co-authored ‘The A-Z of Victorian Crime’.

In 2018 he launched Chronicles Tours, whose current offerings include tours focusing on riots and rebellions, dark deeds in Westminster, the London life of William Shakespeare, the history of Tower Hill, and more.

[…] 10 brutal murders that shocked London […]

[…] 10 brutal murders that shocked London […]