Today sex scandals seem to do little, if anything, to damage a celebrity’s career. In fact, the accused often seem to benefit from the notoriety which can often relaunch their careers. This was not the case some 60 years ago when a series of trials besmirched the reputation of the English Universal Horror Star Lionel Atwill. STEPHEN JACOBS reports on the scandal.

Who was Lionel Atwill?

Lionel Atwill was born in Croydon, Surrey, England on 1 March 1885.

Educated at Mercer School in London, Atwill began a stage career in 1904 when he made his theatrical debut as a footman in the comedy The Walls of Jericho at London’s Garrick Theatre.

In 1915, after touring England and Australia, he arrived in America with Lily Langtry to appear in the comedy Mrs Thompson.

Two years later he was both directing and starring in the play The Lodger on Broadway with his then wife, Phyllis Relph. Within a year he had made his motion picture debut.

In 1930, following his divorce from Phyllis, Atwill married the multi-millionairess Louise Cromwell Brooks, the ex-wife of General Douglas MacArthur.

In December 1931, he began work on the courtroom drama The Silent Witness. It was his first Hollywood picture and he enjoyed the experience. “I’m one of those few stage actors who really like the films,” he said, “and admit it.”

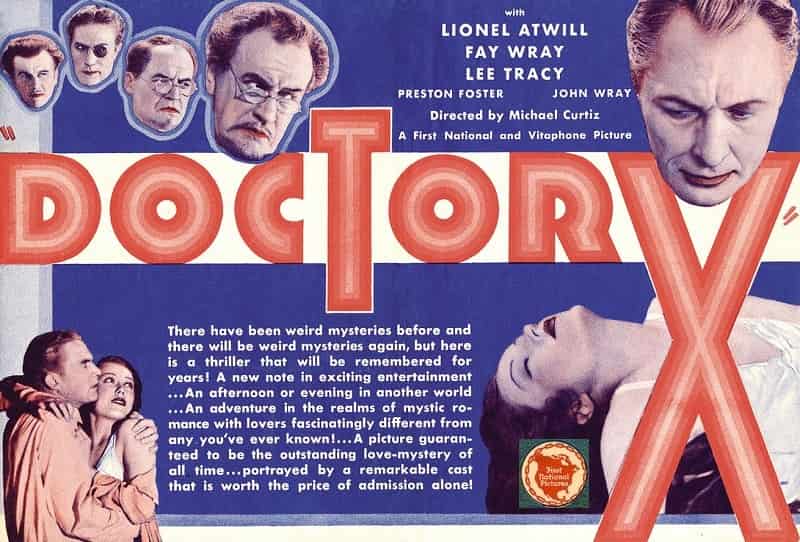

Soon he appeared in Doctor X, the first of three horror movies he made with Fay Wray. The Vampire Bat and Mystery of the Wax Museum (both 1933) completed the trilogy.

Although he then had a varied career, appearing in such pictures as Captain Blood (1935) and The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939), he is mainly remembered for his horror roles, especially as the one armed Inspector Krogh in Son of Frankenstein (1939) – a character whose boyhood encounter with the Monster had ended badly.

“One doesn’t easily forget, Herr Baron,” Krogh tells Wolf Frankenstein (Basil Rathbone), “an arm torn out by the roots!”

Yet within a few years of facing the Frankenstein Monster Atwill was making headlines, for all the wrong reasons.

The first investigation into misconduct

On Thursday, 8 May 1940, the Los Angeles county grand jury began an investigation into claims that a 16-year old girl named Sylvia Hamalaine was mistreated by a number of film celebrities.

Thirteen subpoenas had been issued to both men and women, many prominent within the movie industry.

By the time the jury began taking testimony in early May, however, only a few had responded.

The first witness was a Cuban dress designer, Virginia Lopez, who spoke of a “wild party” during which Hamalaine had been molested.

Despite her testimony, Lopez was not whiter than white.

For, as the county grand jury began its investigations, Lopez and an ex-car salesman named Adolph La Rue, awaited trial in another case concerning the young Miss Hamalaine.

In that case Hamalaine, claimed that Lopez and La Rue had ‘mistreated’ her.

Lopez was indicted due to the assertion that she was present and had condoned the action.

Minnesota-born Sylvia Hamalaine had travelled from her home in Hibbing to seek a film career in Hollywood.

Her parents had been supportive, reportedly supplying their daughter with between $150 and $200 a month in expenses.

She had rented a room at a respectable Hollywood hotel, where many prominent figures in the movie industry lived.

One day, while sunbathing, she met Lopez and La Rue.

Soon Hamalaine and Lopez were sharing an apartment and it was here on 17 December 1940, Hamalaine asserted, that the ‘intimacies’ occurred.

She was seduced in the presence of Lopez.

“She held my hand at the time,” the accuser stated.

She later revealed that she had been intimate with La Rue twice although denied he was the father of her expected child.

Both Lopez and La Rue, then a draftee soldier at Camp Ord, were arrested on charges of statutory rape.

Hamalaine told the jury that, on Christmas night, she and Lopez were taken to the home of an undisclosed actor.

There she saw ‘lewd motion pictures’. Most of the guests disrobed, Hamalaine asserted and, after some urging, she did the same.

A little later she and one of the male guests went into another room together.

The girl’s testimony was corroborated, in part, by Lopez who said she had spent the evening, fully clothed, sitting at the piano playing Viennese Waltzes while the guests stripped in the living room.

This was not, however, the first time Hamalaine had been at the actor’s home. A smaller party had been held a few days before Christmas and on that occasion, too, she had been intimate with one of the guests.

Various others were questioned. A film producer, the husband of a foreign actress, admitted attending the party but denied that anything improper had occurred.

The producer was followed to the stand by an actor named Archie Carpenter who claimed to have taken Lopez and Hamalaine to the party.

Carpenter said it had been a pleasant evening, but no salacious films had been shown and nobody had removed their clothes.

The owner of the house was in the east and, according to the chief district attorney’s investigator, Joseph P. Dunn, was “shocked” to learn he had been involved.

Although he had not been summoned to testify the actor said he would appear before the grand jury on 21 May.

Virginia Lopez told the jury she and Hamalaine had also visited the actor’s home on 26 December accompanied by a friend of the host.

It was that night, Lopez asserted, that Hamalaine was attacked by a “well-known movieland figure”. Incredibly, the girls visited the home again the following night.

On this occasion Lopez witnessed “lewd orgies” and was not allowed to leave until the morning.

She was “innocent and angry”, she said, at the treatment she and her friend had been subjected to.

She also revealed that several members of the movie community had promised to “take care of her” on the proviso that she kept their names out of the investigation.

The next day Hamalaine testified that Lopez had encouraged her to have relations with La Rue, who pleaded guilty that day to the delinquency of a minor.

His probation hearing was taken off the calendar pending the completion of his army service. Lopez was charged with witnessing and condoning the act of 17 December.

Allegation of protecting film industry from assault claims

Lopez’s attorney, Donald MacKay, charged that “members of the district attorney’s office seem to be very anxious to protect certain people in the film industry from involvement,” in the scandal.

Talking of the alleged parties he added, “I would like to show that far worse things happened to her [Hamalaine] at the hands of others than occurred at the hands of my client.”

Percy Hammond, in charge of the grand jury investigation, demanded an apology. MacKay complied but insisted that members of the district attorney’s office were reluctant to investigate the party claims.

He also demanded Hamalaine tell the jury the names of all the men with whom she had been involved.

She named La Rue and one Franz Moritis before shouting, “I’m not telling these other people’s names because they don’t belong to the case.”

MacKay told Hamalaine he was not asking for names, just the number. “I’m sorry,” she replied, “I’m not even telling the number.”

When the Judge intervened to advise Hamalaine to comply, the girl said there had been two more men, in addition to La Rue and Moritis.

On Monday, 12 May 1941 Sylvia Hamalaine was once again questioned by MacKay.

She admitted she had been intimate with at least four men and was uncertain as to who the father of her unborn child was.

She also announced she had been embarrassed at being seduced by La Rue in the presence of Virginia Lopez.

Lionel Atwill named in sex abuse case

Any speculation over the actor host’s identity came to an end when McKay then asked, “And were you embarrassed when you cavorted in the nude at the home of Lionel Atwill last December in front of six people – three of whom you never had seen before?”, MacKay asked.

The District Attorney Silas E. Roll, objected. “The Atwill party is now before the grand jury,” he said, “and should not be dragged into this case.”

The objection was sustained. “I am not saying this evidence is not material,” explained Judge Thomas Ambrose, “but I am saying that it is not wise to admit it in the broad sense of justice. You see, these newspaper people here are taking it down.”

The following day Virginia Lopez was convicted of contributing to the delinquency of a minor. The sentence was set for 9:30am that Friday (she would be sentenced to a year in jail).

Although Lopez was permitted to remain at liberty she was served with a subpoena as she left the courtroom, requiring her to appear before the grand jury that same day to elaborate on her testimony regarding the ‘wild parties’.

On Wednesday additional witness appeared to testify. Lopez was called to elaborate on her previous testimony and Margaret Roth, whose husband, advertising man Charles Roth, had previously testified, was summoned to answer questions.

Pearly Kinney, a maid employed by Lopez on several occasions, and Albert J. Farrell (an employee of the Hollywood apartment were Lopez and Hamalaine lived), also appeared. It was also learned that a number of anonymous communications had been received incriminating other persons in the alleged indecencies.

A young actress named Doris Tresper, named by Lopez as one of those present at the parties, appeared unexpectedly that day and was closeted with the grand jury for half an hour.

Another new witness was Harold Pierce who was said by Lopez to have visited one of the party guests in a Hollywood apartment the day following the affair. There he had heard her account of the asserted mistreatment. Lopez was questioned briefly before the jury was adjourned until the following Wednesday when Lionel Atwill was due to appear to give his version of events. He had vehemently denied all accusations and hinted at the possibility of a “shake-down”.

Atwill denies all accusations and gives testimony

On the 21 May, Lionel Atwill appeared before the grand jury. He was wearing a black armband in mourning for his son, John Anthony Atwill, 21, who had recently been killed in action with the R.A.F.

The actor spent three hours before the jury and, upon leaving the court, he announced, “I have returned from New York to testify voluntary, and intend to remain here until my name is cleared. I emphatically and categorically denied all charges that any improper acts occurred in my home or that any indecencies took place in the presence of the Hamalaine girl. Mr. Frencke, a friend, did visit me to discuss a theatrical matter and some of the other persons who have been mentioned were present briefly”.

He said he assumed the grand jury had finished hearing his version but he would remain available for further questions.

On Monday, 2 June 1941, the county grand jurors wound up the investigation with the announcement that “lack of competent testimony warrants no further inquiry at this time.”

The jury’s foreman, Theodore F. Pierce, issued the following statement: “Some of the testimony in this case is such as to tax the credulity of the jury. For this reason no formal action is being taken and none is contemplated in the light of present evidence. It is indeed regrettable that the names of certain prominent people were bandied about so freely and apparently without facts to back up the assertions.”

And that was the end to the case… or so it seemed.

The second investigation

A little over a year later, on the 11 June 1942, Lionel Atwill appeared again before the county grand jury, this time in a secret reinvestigation into Sylvia Hamalaine’s charges.

On the advice of his attorney, George Stahlman, Atwill refused to testify concerning the charges. He was promptly excused.

Members of the new 1942 grand jury, in office for a little over two months, had expressed dissatisfaction with the 1941 findings and, as a result, had planned to re-examine the charges and re-open the case. As a result, Atwill and additional witnesses were issued with subpoenas.

Lionel Atwill indicted with perjury charges

On Tuesday, 30 June, Atwill spent more than an hour before the jury at the end of which he was indicted with charges of perjury while testifying before the 1941 grand jury.

His bail was set at $1,000. Atwill’s attorney, Isaac Pacht issued a statement which said, in part: “The charge against Mr Atwill was thoroughly investigated by a previous grand jury and found to be baseless. Mr Atwill will press for the earliest trial possible when his innocence will, I am sure, be completely established.”

Two days later, Atwill stood before Superior Judge Edward R Brand and entered his plea of “Positively not guilty.”

He was ordered to appear on the 17 August to face the charges.

That same day Lucile M. Hulse, the official stenographic reporter, filed a transcript of both the 1941 and 1942 grand jury testimonies making the evidence against Atwill public.

It stated that some six people had described what had occurred at Atwill’s parties. Those giving the most details were Hamalaine and Archie Carpenter. Katherine Marlowe, an actress, told the court that she had heard Carpenter’s claims that he might get $5000 from Atwill and others because of what he knew about the parties.

That Sunday, Marlowe reported to the police that she had been threatened and ordered to “get out of town” by unidentified persons apparently interested in preventing her from testifying at Atwill’s pending trial.

Witness threatened not to testify

The actress told police that she had received threats of bodily harm during the inquiry and that since Atwill’s indictment she had, on at least four occasions, received threatening phone calls from unidentified men.

“The callers spoke very vulgarly and nastily, telling me that if I did not leave town ‘something would happen’,” she said. “I am afraid.” The police advised her to inform the District Attorney’s office of the calls.

Later that month, more people were called to answer the grand jury’s questions. Witnesses called included Doris Tresper, Elaine Waters, Evelyn Moriarty, Katherine Marlowe, Sandra Shaw, Paul Bolton, Richard Carpenter, Betty Adams, Alfred Strauss, and others.

On 11 August, Lionel Atwill was indicted on a new perjury charge by the county grand Jury.

His persistent sworn denials were renewed, resulting in a second charge of perjury. The trial for both indictments was set for the following month and Atwill was released on a $2,500 bail.

Atwill enters guilt plea to perjury over ‘immoral films’

On 24 September, Lionel Atwill entered a guilty plea to one count of perjury in connection with his previous denial that he had ever owned or exhibited immoral motion pictures (he had admitted possessing ‘improper films’ but stated these had been exhibited at a gathering not touched by the investigations).

His attorney, Issac Pacht, told Superior Judge William R. McKay that Atwill had “lied like a gentleman,“ when he had told the jury he had never possessed or shown the films.

He did so to protect from embarrassment British friends who were visiting him at the time.

Stricken from the charges, however, were portions of the indictment referring to asserted immoral acts by guests at Atwill’s home.

In presenting a motion to strike this portion of the accusation Deputy District Attorney Arthur Veitch pointed out that, if the case were to go to trial, the witnesses for the prosecution would probably consist only of persons with criminal records.

Atwill’s hearing on probation and sentence was set for 15 October, when Judge McKay granted the actor five years probation.

On 16 April the following year Atwill made a plea for the termination of his sentence. He had had difficulty in obtaining employment due to the stigma of his sentence, the actor told Judge McKay. Atwill’s attorney also spoke of the “abject humiliation” his client had suffered and said he thought the ends of justice had already been accomplished.

Although Atwill’s probation officers had told the judge that the actor’s conduct had been “exemplary” during the probation period Judge McKay told Atwill that the officers had recommended his sentence not be terminated because of “what the man in the street might think of a man sentenced to five years getting off in six months.”

When the judge asked Atwill whether it was a rule of the Hays office to refuse work to persons on probation the actor replied, “The studios don’t want to offend you but they put you off. It’s a sort of unwritten law.”

Conviction squashed and wife sues for divorce

On 23 April, after studying the actor’s employment status, Judge McKay made an unusual decision: he gave gave Atwill permission to change his plea from guilty to not guilty—and then promptly dismissed the perjury indictment against him. “You are now in the position where you can truly say you have not been convicted of a felony,” the Judge told the actor.

The following month Atwill’s wife sued for divorce, charging desertion and misconduct. They had, she said, separated four years earlier.

The divorce was granted in June 1943 but Atwill did not remain single for long. On 7 July 1944 he married divorcee Mary Paula Pruter, a radio singer and producer, in Las Vegas.

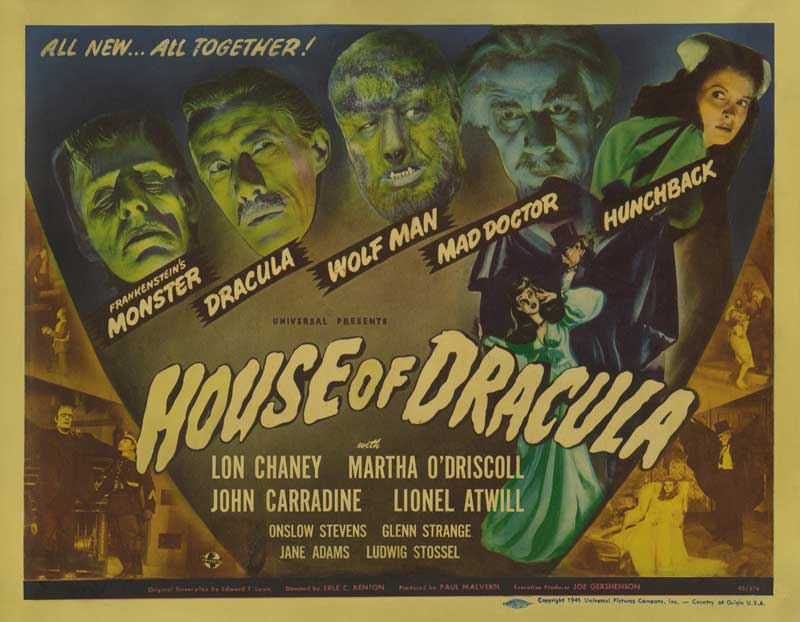

Following the trial Atwill worked, making serials, B movies and the final two pictures in Universal’s Frankenstein series: House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula.

Lionel Atwill dies aged 61 years old

On 22 April 1946, six months after his wife presented him with a baby boy, Lionel Jr, Atwill died at his Pacific Palisades home. The cause of death was reported as pneumonia. He was 61 years old.

These court cases constitute a scandal that has never gone away, which is a pity.

For Lionel Atwill deserves to be remembered for better things – and not the events that happened during a few parties at his Pacific Palisades home in late 1940.

Award-winning Boris Karloff historian STEPHEN JACOBS is the author of Karloff: More than a Monster. You can buy his book here from Amazon and read his interview with The Spooky Isles here. He also wrote an Spooky Isles article Karloff’s London, a location guide including Boris Karloff’s childhood homes and filming locations around the English capital.

Please… The events HAPPENED at the parties. They TRANSPIRED — became known — after the parties.

Merriem Webster lists the primary definition of “transpire” as “to take place, or occur”.

“To be one known” is only the secondary definition.

They should have remained personal and private.Lionel’s name is forever besmirched,and he never indulged in having sex with underage girls.Disgraceful to tarnish wrongfully a great actor!.

Yeah same for Roman Polanski….that’s sarcasm.

A chap named, Alex Hopkins, furnished a website going by the name of Classic-Monsters.com with a write up about this subject. He ludicrously insinuates that Atwill was a “sociopath” or “psychopath”. Here’s the comment I left at that site:

“Got something to say?” Aye. All this talk of “sociopaths” and “psychopaths”. They’re medical terms, hardly applicable to working actors making a living as best they can. Atwill, like many others in the Hollywood hills of sunny California, found a niche for himself portraying a certain type of character that the paying audiences came to expect of him, regardless of reality. Therefore he was exploited by the film industry, and can hardly be blamed for his continued employment in the type of part that the studio knew the cinema-going audiences expected to see him in. It seems to me that a large percentage of the audiences of those times possessed a good deal more sophistication than is bestowed on modern commentators and horror film fans. They enjoyed and accepted those films as the tuppenny ha’penny yarns they were. They didn’t take ’em in deadly earnest. The fact that Atwill continued to be employed in the roles that paying customers were accustomed to seeing him in, almost up to the time of his death, is not as “curious” as one commentator seems to think. Arbuckle was implicated, rightly or wrongly, in a scandal that involved the death of a young woman. What did Atwill do? Throw parties at which blue films were shown. The imagination boggles at the modern world(!)