For centuries, London Bridge employed the Keeper of the Heads to maintain gruesome displays of decapitations, writes RICHARD CLEMENTS

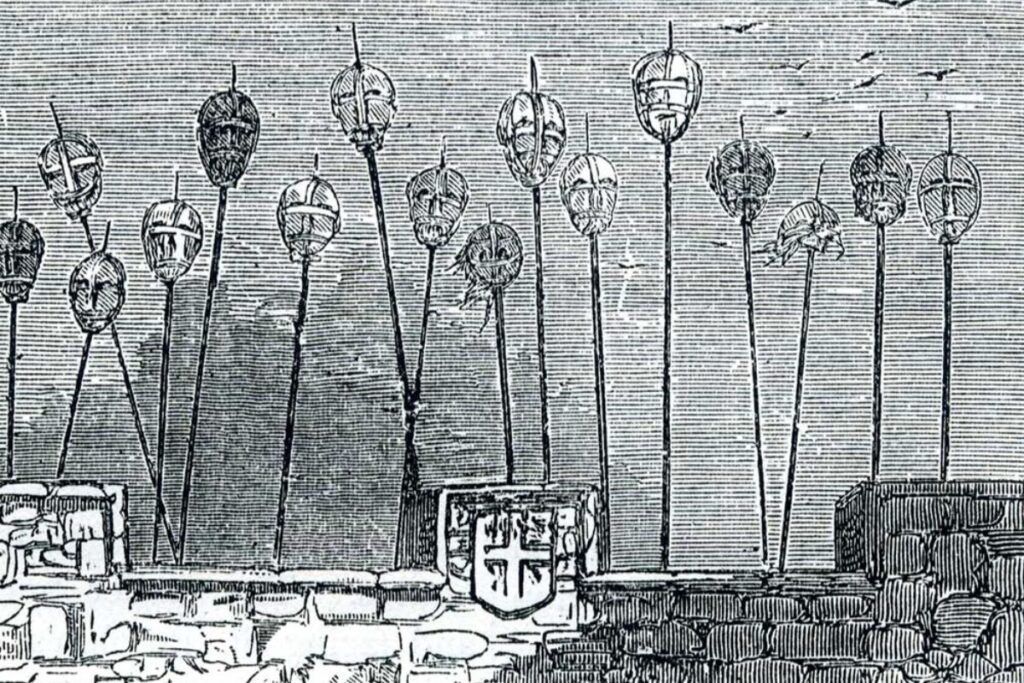

For over 300 years, London Bridge served as a macabre gallery of the executed, where the severed heads of traitors and criminals were displayed to instil fear and uphold the authority of the Crown.

Amidst the bustling activity of medieval London, a figure with an unusual job title was also at work known as the Keeper of the Heads, played a crucial role in maintaining this gruesome tradition.

Tasked with the preservation, display, and disposal of decapitated heads, the Keeper’s job although macarb was pivotal in the city’s history.

This article delves into the history and duties of the Keeper of the Heads, shedding light on one of the most unusual occupations of the past.

The practice of displaying executed heads on London Bridge began in the early 14th century, serving as a warning to those who dared to defy the monarchy.

The first recorded instance was the head of William Wallace, the Scottish rebel leader, displayed in 1305 after his execution for treason against King Edward I.

This grim tradition continued through the centuries, with heads adorning the spikes on Drawbridge Gate at the northern end and later on Stone Gate at the southern end of the bridge.

The Role of the Keeper of the Heads

The Keeper of the Heads which was a royal appointment was responsible for the maintenance of this display. His duties included receiving the freshly severed heads, from Tower Hill and Tyburn preserving them, mounting them on spikes, and eventually disposing of the remains.

The Keeper operated under the orders of the monarchy and local authorities, ensuring that the heads remained a potent symbol of the Crown’s power.

To ensure that the heads remained visible and recognisable for as long as possible, the Keeper employed various preservation techniques. Heads were often boiled and then dipped in tar, which helped to slow down decomposition and protect them from the elements. This process ensured that the heads could endure weeks, months, or even years on display, serving as a continuous reminder of the consequences of treason.

Once preserved, the heads were mounted on iron spikes and placed high above the bridge. The Keeper had to ensure that the heads were securely fastened and prominently displayed. This required a meticulous approach, as the spikes needed to penetrate the skulls firmly to prevent them from falling. The positioning of the heads was crucial for maximum visibility, making the job both physically demanding and psychologically taxing.

Notable Heads and Their Stories

Throughout the centuries, many high-profile individuals found their final resting place above London Bridge. These heads belonged to notorious traitors, political dissidents, and enemies of the state, each with a story that reflected the turbulent times.

William Wallace

As mentioned earlier, William Wallace was the first prominent figure to have his head displayed on London Bridge. His execution and subsequent display marked the beginning of a long tradition of using severed heads as a deterrent against rebellion and treason.

Thomas More

In 1535, the head of Sir Thomas More, a former Lord Chancellor who defied King Henry VIII’s separation from the Catholic Church, was placed on the bridge. More’s steadfast refusal to accept Henry as the supreme head of the Church of England led to his execution for treason. His head remained on display for an extended period, reportedly remaining remarkably well-preserved when it was finally taken down at his daughter’s request.

Guy Fawkes

Another infamous head to grace the spikes of London Bridge was that of Guy Fawkes, one of the conspirators behind the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Fawkes and his fellow plotters sought to blow up the Houses of Parliament, but their plan was foiled, leading to their execution. The display of Fawkes’ head served as a powerful warning against similar acts of treason.

The End of the Practice

The practice of displaying heads on London Bridge began to wane in the late 17th century. By 1678, the tradition had largely ceased, with the last heads being removed from the bridge.

From then on, notable executions saw heads displayed at other locations, such as Temple Bar and Westminster Hall. The decline of this practice marked a shift in societal attitudes towards punishment and the display of state power.

The Keeper of the Heads held one of the most unusual job roles in medieval and Tudor England, maintaining a gruesome tradition that aimed to deter rebellion and enforce the authority of the Crown.

The severed heads of traitors displayed on London Bridge served as a constant, reminder of the consequences of defying the monarchy.

As London evolved, the practice of displaying heads faded into history, but the legacy of the Keeper of the Heads remains a chilling testament to the brutal methods once employed to maintain order and control.

Tell us your thoughts on this article in the comments section below!

RICHARD CLEMENTS has always been fascinated by all things unexplained and unusual, particularly in a historical context. He has a strong interest in the paranormal and supernatural, and he was the founder of Parasearch Radio. Richard also worked alongside Kerry Greenaway and Paul Rook on the paranormal podcast show Paranormal Concept. He is now putting pen to paper, writing articles he believes will interest those who enjoy reading about the lesser-known aspects of the past and the unexplained.

Fascinating! Originally from London, I now live in York, where we have the City Walls with their Mediaeval Bars, the southernmost of which is Micklegate Bar, once the ceremonial entrance from the London direction. Heads were displayed on the Bar until as late as 1746 (one can only assume we were then something of a provincial backwater and slightly behind the times). Travellers would go out of their way to avoid entering the city via the Bar on account of the rotting heads that might plop down on top of them.

One thing I was wondering was, Did the Keeper of the Heads do all this work himself? Or did he employ staff? If so, do we know how many? Was his role of a managerial/supervisory nature, or possibly just a ceremonial one?

Thank you for your insightful comment and intriguing question regarding the role of the Keeper of the Heads. Here’s some additional context based on the available historical accounts:

The role of the Keeper of the Heads was indeed a unique and somewhat grisly occupation. From the historical records we have, it appears that the Keeper’s responsibilities were not merely ceremonial. His duties were quite hands-on and essential for maintaining the fearsome display that symbolized the power of the Crown.

The Keeper was tasked with the preservation, display, and eventual disposal of the decapitated heads, which required a fair amount of gruesome manual labor. Techniques such as boiling and tar application were employed to preserve the heads, suggesting a role that involved more than just oversight. This indicates that the Keeper had to be directly involved in the physical preparation and maintenance of the heads.

As for whether the Keeper employed staff, historical records on this are quite thin. There is no substantial evidence to suggest a team of workers was involved, but given the labor-intensive nature of the tasks, it is plausible that the Keeper might have had assistants or laborers to help with some of the more physically demanding aspects of the job. However, the specifics of the workforce structure and the number of people involved remain largely undocumented.

To address the question about whether the role was managerial or ceremonial, it seems the Keeper’s position was more operational than managerial, based on the responsibilities documented. The Keeper had a direct and practical role in ensuring the heads were properly displayed and maintained.

I am currently collaborating with the Museum of London staff to delve deeper into this topic. Our ongoing research aims to uncover more detailed information about the Keeper of the Heads and the potential employment of staff in this role. The museum’s archives and other historical documents might provide further insights into the day-to-day operations and organizational structure of this peculiar occupation.

Thank you again for your interest and thoughtful questions. They are valuable in guiding further research into this fascinating aspect of London’s history.