RICHARD PHILLIPS-JONES looks at one Hammer project that never saw the light of day

It’s 1957, and Hammer Films are planning their follow up to The Curse Of Frankenstein. An adaptation of Dracula is in pre-production, with a view to release the following year. Both films will set the template of what is regarded as the great British Gothic cinema tradition, and kick start the form’s golden age. But you already knew that.

What if I told you that Dracula wasn’t the only horror subject Hammer were planning at the time? Or, that they had enlisted the services of one Richard Matheson, already well on his way to becoming one of fantasy literature’s most important figures of the 20th century?

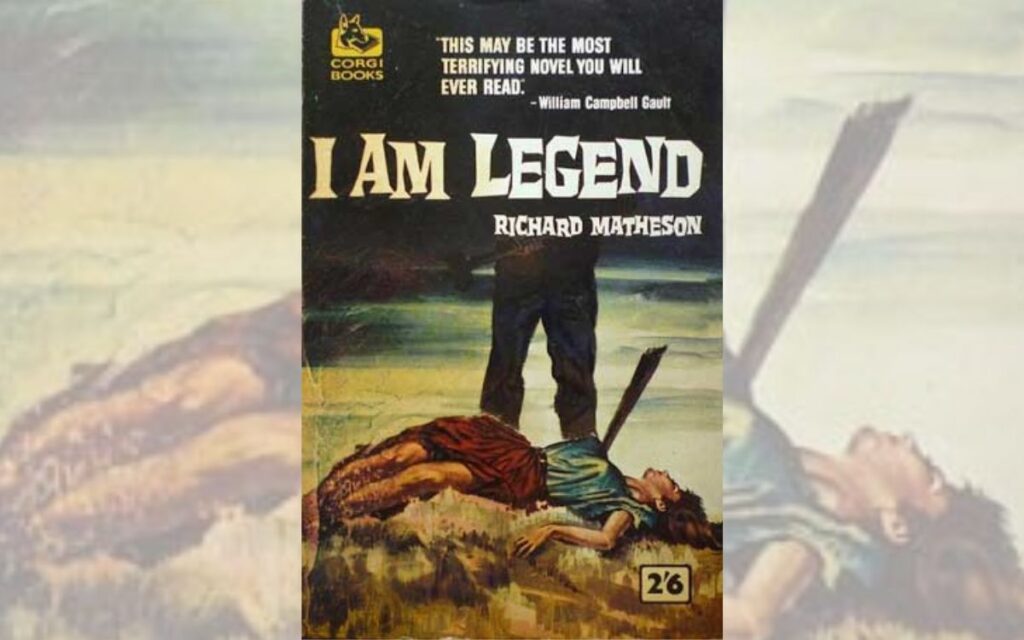

Matheson’s screenplay for Universal’s The Incredible Shrinking Man had raised his profile in the film world no end, and his 1954 novel I Am Legend grabbed Hammer’s attention. Its tale of a near future world in which the human race has turned into vampiric creatures perhaps offered a follow-up not only to the Frankenstein film, but to their sci-fi horrors of the previous few years. At what must have been quite a cost to the company at the time, Matheson was flown to Britain with a view to adapting his book into a screenplay, which he retitled The Night Creatures.

Closely following the novel for the most part, the script concerned one Robert Neville, apparently the sole survivor of this unknown plague. The story follows Neville as he firstly tries to come to terms with and understand his predicament, before embarking on the search for a cure, whilst flashbacks detail the loss of his wife and child, as all around him succumb to this mystery virus.

It was common practice at the time for film producers to send a script to the BBFC for comment, in order to see if any changes were required in order to meet their desired classification. Whilst the company’s experience with the Frankenstein picture would have braced them for reservations from the censors, the actual response must have been quite a shock – the board made it clear that they would not consider giving a certificate to any film made from the existing screenplay. To make matters worse, America’s MPAA expressed their own concerns about the script, making that crucial US co-funding unlikely.

So, what exactly did the censors object to? Well, there are multiple stakings, as well as an uncomfortable scene in which Neville conducts tortuous experiments on a female vampire. Beyond that, even though the script dilutes the killer punch of the novel’s ending, the sheer apocalyptic nature of the piece may have been enough to worry the censors in its own right.

Hammer, already walking a tightrope in keeping the BBFC placated, abandoned the project. They sold the script to their former production partner Robert Lippert, and after further rewrites it was eventually filmed in Italy as The Last Man On Earth (1964). Tellingly, Matheson wasn’t happy with the result, changing his name to Logan Swanson on the credits. Even with that in mind, it’s a fine film in its own right, Vincent Price’s moving performance raises proceedings considerably, and it’s the only adaptation which stays relatively true to the plot of the source novel. It’s also worth noting its influence on Night Of The Living Dead (1968).

By the time the story reappeared as 1971’s The Omega Man, Charlton Heston was battling not vampires but albino mutants. This same change was carried through to 2007’s I Am Legend, which reinstated the original title but was, in reality nothing more than a reboot of the Heston picture.

Thankfully, Matheson would collaborate with Hammer again for both Fanatic (1965) and The Devil Rides Out (1968), but this lost project is a tantalising teaser. Had it been made, and then been a success, how would it have influenced Hammer’s future? Would there have been a greater emphasis on more horror pieces with contemporary settings, sitting alongside their Gothic triumphs? And, if so, would the company have been better placed to cope with the shift in trends when The Exorcist hit screens in 1973? Speculation perhaps, but the possibilities are fascinating to consider.

In trying to hazard a guess at what the finished film might have looked like, it’s worth considering Hammer’s choice of director. Val Guest helmed the company’s first two Quatermass films, so in retrospect seems a natural choice for the project, particularly if you look at his 1961 classic The Day The Earth Caught Fire. Guest’s depiction of an increasingly deserted city, the eerieness of the abandoned streets and buildings, not to mention the lone wanderings of its central protagonist would have suited Matheson’s tale to a tee.

A lost opportunity indeed.