Hammer horror monsters were key to the studio’s gory success. Guest writer ELLIOT CHAPMAN picks his favourites from Hammer’s lists of classic films…

Monsters! We need them.

As the science fiction author, China Mieville opines, we are driven to make monsters part of ourselves.

In 1975, Steven Spielberg got a summer blockbuster out of our fear of being eaten by something from the natural world – the Great White Shark in Jaws.

Ridley Scott took that further, in 1979 with Alien, by making us fear a predator that wasn’t all that unlike us (bipedal, intelligent) and made up of a perversion of human sex organs coming back to savage us.

It was rooted as much in the fear of rape and pregnancy as it was in the fear of a predator further up the food chain than us.

In a sense, both films were also a part of the displacement of the overt gothic tradition that was winding down for Hammer Films in the 1970s. The studio was enjoying a few last gasps of, rather smuttier, Brit horror… before oblivion (though, delightfully, as the gothic is the return of the repressed, Hammer’s story wasn’t to end forever).

Monsters were essential to Hammer, of course.

We went to them, as the generation before had gone to Universal and later generations to the slasher movies of the 1980s with their Jason Voorhees and Kruegers and Myers, to find them – chimeric creatures that entertain us.

In its brilliant way of course, Hammer was the full-blooded and gaudy colour re-packaging of the Universal Horror movies of the 1930s and 40s. In a sense, they brought the Gothic Romance back home to Blighty.

In place of studio sets shot through the distorting lens of doggerel German Expressionism, rich location shoots in cracking woods about 20 miles outside of London, and the full deployment of costumes, props and scenery by designers with the gift of recreating the Victorian era on screen.

But with which monsters did Hammer really grab our imaginations? Which worked their way into our collective sub-conscious and stayed there long after Hammer had lost its footing?

Various ones spring to mind: Oliver Reed as the cursed man who becomes wolf in Curse of the Werewolf (1961); Jacqueline Pearce as the eponymous The Reptile (1966) and Christopher Lee bandaged up as The Mummy (1959) to bring death to the desecrators of a blind pyramid in Egypt.

But after a little pondering, this is our – in places perverse, in places predictable – list of “gruesomes”.

But perversity and predictability were, appropriately enough, things Hammer built its legacy on…

Hammer Horror Monsters

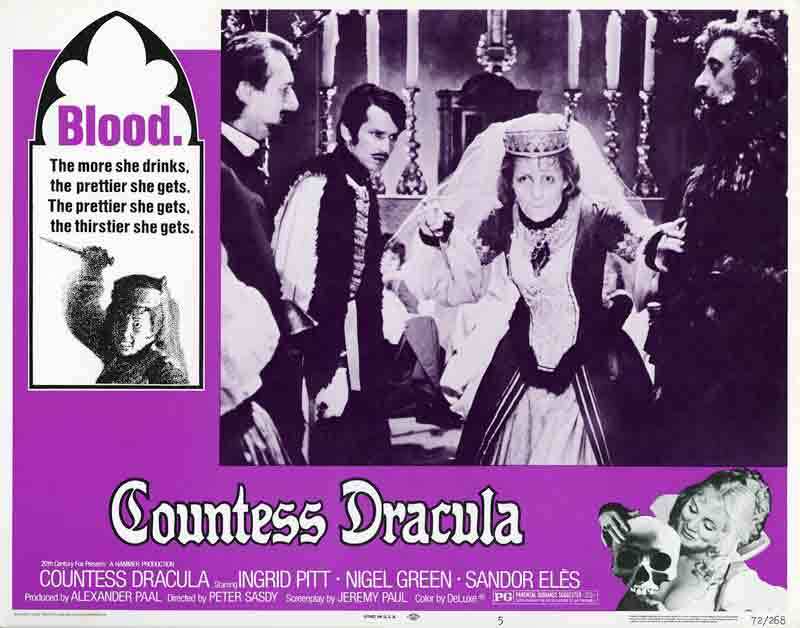

1. Countess Dracula

Dracula wanted to bite you – draw out your very lifeblood and, perhaps, make you a consort, if he so chose.

In Countess Dracula (1971), Elizabeth Nadasdy (played by Hammer legend, Ingrid Pitt), wished to stay young by literally bathing in the blood of her nubile servants.

One cannot escape a certain sexism in the depiction of a woman vampire (of sorts) wishing to stay young and beautiful.

Almost the same premise works its way into Captain Kronos (1974), which is also shot though with paranoid women taking any supernatural precursor to cosmetic surgery as a means to stave off the horror of growing old.

But the success of this particular Lady Bathory is Pitt herself. She is alluring, unsettling and monstrously obsessed; she hits every intention of a character so desperate to run from the corruptions of Time that she will kill to do so.

The strength of Countess Dracula (as with Captain Kronos and She, starring Ursula Andress) is the haunting reminder of our finite lives and our bodily decay.

In these stories, death is not feared so much as the slow but irrevocable loss of that unique beauty that only youth can endow.

As such, the monstrousness of the Countess is linked to our vanity and even how our society sidelines the very old – in Captain Kronos, the ageing aristocratic vampire played by Wanda Ventham is literally hidden away in her stately home… The fear of physical corruption is so great that it must be driven into the shadows.

2. The Arthropods

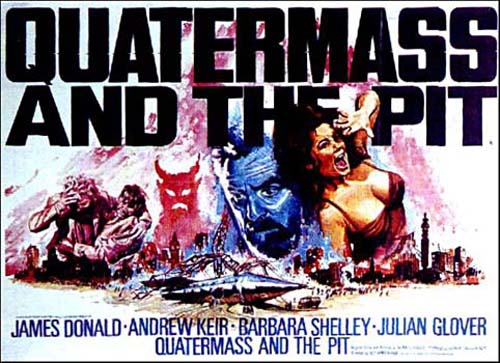

It’s debatable whether Hammer’s adaptations of the classic BBC Quatermass serials of the 1950s falls squarely into horror or science fiction. But, if the latter, they are filled with the former.

The third and final adaptation was Quatermass and the Pit from 1967.

The monsters do not actually appear for an awfully long time. Indeed, when they do – they’re dead. Rotting corpses of insectoid Martian life, discovered in the buried hull of an alien space craft, sent to Earth millions of years earlier.

For a while, Professor Bernard Quatermass (Andrew Keir) and his associate, Dr Matthew Rony (James Donald) posit the origins and motivations of the monsters.

Is it possible that they were once our neighbours in space; that they took early Man to Mars and operated on him to the point where they had instilled race memories enough to perpetuate their own dying culture in some way?

The unorthodox scenario of Quatermass and the Pit vis-a-vis its monsters (three legged arthropods with stubby horns) is how they are completely rotting away by exposure to foul London air by this point. So, how are our heroes going to be threatened?

And then the horror (and the monstrousness) finally begins… The alien race memories in human beings are reactivated by the hull of the space ship itself. The descendants of the Martians instigate an immediate racial purge, killing any person without their genetic inheritance.

We become the monsters…

Moreover, in a horrible symbol of triumph, the hull disintegrates into an image of a Martian. And the image rises over London, a blazing and malevolent form above a street called Hob’s Lane (a name for the devil itself) looking every inch like the horned beast…

The fusion of science fiction and biblical horror is made in one terrifying moment, as madness and killing spreads across the capital.

Even after the horror is defeated, it is with the awful realisation that we contain a monstrous taint within us that can be re-activated at any time in the future.

In a sense, it’s pure original sin stuff, or a rather conservative notion that our tendency towards racism is genetically encoded somehow (rather than something motivated by politics, economics and imperialism). But the execution by Hammer is raw, gaudy and incredibly unsettling.

Of course, the notion that monsters are within us is primal, as well as politically loaded.

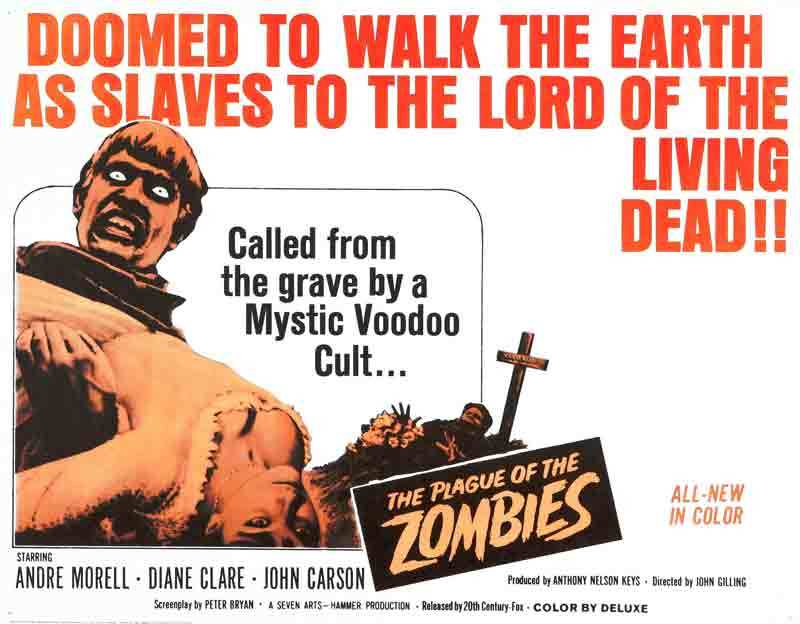

3. Zombies

Arguably, one of the most unsettling moments committed to film by Hammer Studios is actually a dream sequence… Our heroes in Plague of the Zombies from 1966 are menaced by the bodies of the dead, rising from graves in a disorientating, mist-enshrouded sequence George A. Romero would have adored.

The zombie was analog to slavery and ‘Plague’ delves into the Haitian references of the dead reduced to endless labour from the get-go.

John Carson plays the white slave overlord working them in a mine to provide him with profit, via the misuse of voodoo, naturally.

The success of Plague of the Zombies is how it does that neat trick of telling a cracking horror story, while smuggling in neatly subversive ideas the audience may engage with, but which don’t smother a thoroughly ripping yarn!

There is a great deal to be said about how the working day is made up of “dead time” and this film takes that to its wonderfully absurd conclusion. These workers are so alienated they’re not even alive any longer… They are products! They truly experience work as a living death because they are the living dead.

But, beautifully, they have their day. It’s the reason they make this list – it’s not just the highly effective make-up and requisite lumbering. Just those aspects do not make them memorable.

Rather, it’s because they gain agency enough to change where the story is going. They are the monster that has revenge – indeed, they are the beasts of burden that revolt.

Very often, the monster is just there – pushed around by the plot and appearing to provide the moment of horror. And, while this isn’t untrue of the zombies, they do get a pay-off.

Like the Creature finding the true monster not in itself but in its creator Frankenstein, it’s Squire Clive Hamilton (Carson) who is the true locus of monstrousness and it is he that burns along with them in the raging (purifying?) fire come the end.

The revelation that the monsters are the victims and the true monster is one of us is a oft-repeated device. But it is oft-repeated because it has such power to make us confront the evil that men do.

And it is telling how frequently what appears monstrous is actually the oppressed and exploited victims dehumanised to the point where we believe them to be monsters.

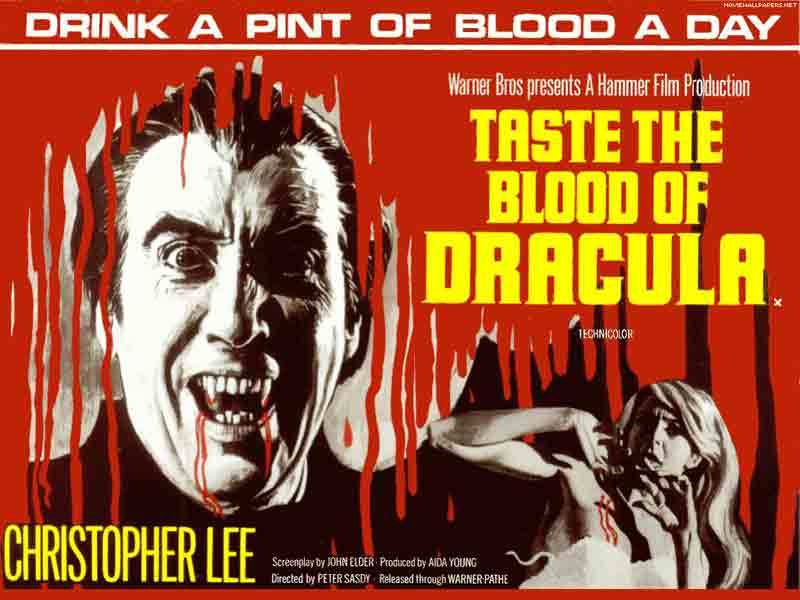

4. Dracula

Bram Stoker’s Dracula might not possess the sheer brilliance of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in its original form (though it is a good read, especially in its early stages).

Indeed, it’s pretty much a racist Victorian bodice ripper. However, it occupies very much equal space in our imaginations, also largely due to the myriad film adaptations.

Christopher Lee had a tough act to follow as Hammer’s fanged Count; Bela Lugosi had played Dracula for Universal in 1931 (as well as countless times on the stage), even though he was a late replacement for Lon Chaney.

In fact, he only played it on the big screen twice – the second time in the gloriously absurd Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. But, to many prior to Lee’s ascendance to the rank of Count, he was definitive.

In a sense, Lee was absolutely right as a successor – his height, dark looks and ominous face creating the initial impact, before his cultured, sonorous voice offered an unsettling disparity between cultivation and the savagery that surely must be lurking just underneath that urbane surface.

And savage he could most definitely be – his eyes blazing red, the fangs bared and the face drawn into a cruel snarl, he eventually dispensed with dialogue altogether for a mixture of straight-backed stillness and animal-like frenzy!

By the time of Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), Lee finally seemed to hit the right age to suggest the gravitas the part truly required.

Moreover, the movie put him in the position of anti-hero – an “angel with horns” taking on and trouncing the rotten Victorian edifice, as represented by a group of ageing libertine hypocrites (including Place of the Zombie’s John Carson), who are also pillars of the community in which the action is set.

The Count was perfect for such a scenario – originally created as an expression of the resentment felt by the aspiring middle-class for the privileged aristocracy, the vampire was a representation of old feudal monopoly (it could even recreate in its own image and thus perpetuate that monopoly).

In a sense, Taste is the return of the old lord taking apart the bourgeois free-traders. The return of the repressed, indeed!

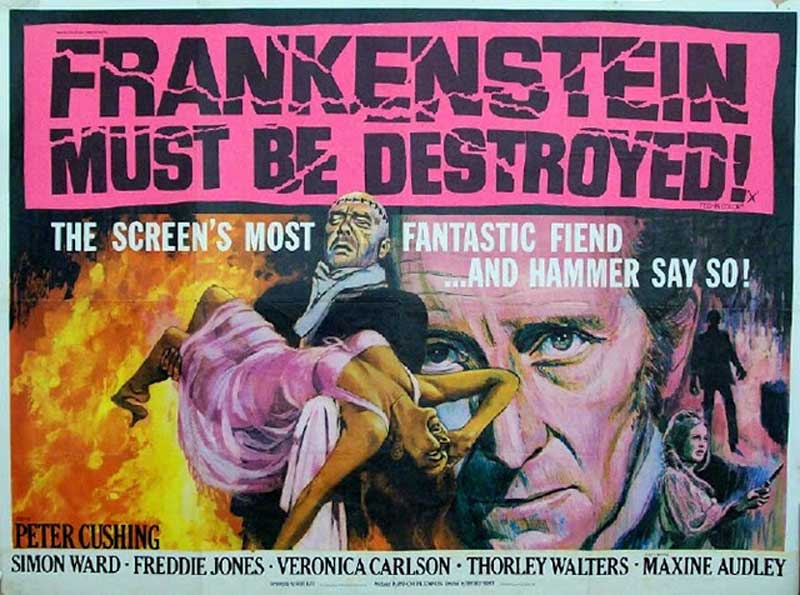

5. Frankenstein

There’s a trick pedants like to pull when they remind us that Frankenstein is the creator not the monster. Ah, if only that were so…

With Peter Cushing, Victor Frankenstein was most certainly the monster.

By degrees, his various creations – following in the tradition of Mary Shelley’s original and the Universal versions of Karloff, Chaney Jnr, Lugosi et al. – are tragic outsiders who evoke our sympathy because they have been dragged into a life that is not their own.

But the Baron Victor of The Curse of Frankenstein isn’t a manic scientist hoping to create life – he’s a cold, calculating and ruthless aristocrat who is determined to alter the course of human history and evolution, at any price.

Interestingly, around the soft reboot (though such terminology would have been unknown in the 60s) of The Evil of Frankenstein, the Baron is at his most sympathetic and even likeable!

But then, the Hammer Frankenstein cycle (with few exceptions), never really played fair with its titles. What Curse? What Revenge? Was he so Evil in that one? He doesn’t actually Create a Woman. And, the Monster from Hell (which sounds cool!) never actually materialises… just some guy with a wrestler’s build who’s been stuffed in a malformed chimp’s outfit.

But, for the most part, Cushing’s Victor Frankenstein absolutely must take the top spot of Hammer’s monsters.

As a character, he murders, he rapes (rather unfortunately for Cushing, who tried everything to get out of a rape scene crowbarred into the otherwise superb Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed), he betrays and he even substitutes himself for men of the clergy who get executed in his place!

Inevitably though, much of this is also down to his performance. Monsters that are grunting spectres in prosthetics might have a superficially startling impact.

But there’s no substitute for a monster played by one of the finest actors Britain has ever produced, especially when the monster exists under the civilised veneer of a calm, understated English gentleman, though one who can fly into the most energetic displays of physicality, which makes him dangerously unpredictable.

Whether casually trepanning or manically attacking anyone foolish enough to try and interrupt his experiments, Victor Frankenstein shifts further and further into our ideas of the monstrous with each passing movie.

ELLIOT CHAPMAN is a jobbing actor, probably best known to fans of Doctor Who as the companion Ben Jackson in the audio adventures by Big Finish. However, his stage credits include playing Renfield in Liz Lochhead’s ‘Dracula,’ which is a little more relevant to his article on the monsters of Hammer! He lives in Bristol with his wife and manic whippet and is a lifelong fan of Hammer, having been introduced to the films – at far too young an age – by his father in the 1980s.