KAJA FRANCK ponders whether the Dracula’s Guest short story published in 1914 was really a prequel to Bram Stoker’s vampire classic Dracula

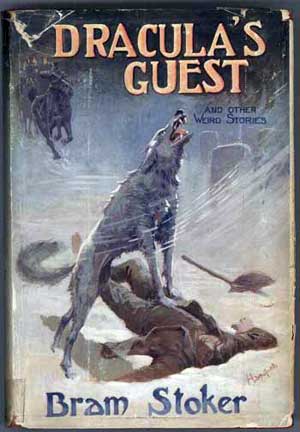

In 1914, as part of the Dracula’s Guest and Other Weird Stories, Bram Stoker’s short story ‘Dracula’s Guest’ was published.

Given the title of this short story and its author, there have been claims that it is the lost first chapter of Stoker’s most famous work, Dracula (1897).

Certainly there are elements in ‘Dracula’s Guest’ which suggest that it could fit within the wider work.

It retains the unsettling Gothic quality of the novel and is replete with standard spooky fare: pathetic fallacy, an abandoned village, the undead, and even a potential werewolf.

Stoker’s interest in folklore is also evident as it is set on 30 April – Walpurgisnacht – and pays heed to the tradition of burying suicides at crossroads.

These elements give the text an authenticity which entices the reader to believe it is more than authorial flair that brings this story to life.

What is Dracula’s Guest about?

The story opens with a young English man, who remains unnamed throughout, setting off from his hotel in Munich – home of Oktoberfest – see the sights including the aforementioned ‘unholy’ abandoned village.

Like any good Gothic tourist he ignores the hotelier’s warnings to arrive home before nightfall as it is Walpurgisnacht when ‘the devil was abroad – when the graves opened and the dead came forth. When all evil things of earth and air and water held revel’ (p. 62).

His carriage driver, Johann, explains that village was abandoned due to an epidemic of vampirism.

Overcome with fear Johann refuses to take the young man any further. Our hero utters the fateful line ‘Walpurgisnacht doesn’t concern Englishmen’ (p. 59) and heads into the twilight. His foolhardy nature is his downfall.

Get Dracula’s Guest ebook for free from Amazon

Though enamoured of the picturesque surroundings, the young Englishman quickly finds himself lost in the dark as a snow storm encroaches.

He finds himself in a graveyard by a large tomb on which is written the words: ‘Countess Dolingen of Gratz in Styria Sought and Found Death. 1801’ (p. 62).

Through the top of the tomb is driven a large spike on which are written the words “The dead travel fast” – a quotation from ‘Lenore’ (1774) by Gottfried August Bürge.

This Gothic ballad features an undead lover coming back to take his bride and was said to be an important influence on British and Irish vampire literature. The tomb opens revealing a beautiful young woman, the Countess.

Our hero is momentarily entranced before being dragged out of the tomb by an unseen force.

He awakens to discover a wolf lying on his chest licking his throat.

The wolf is scared away by the arrival of soldiers who declare that it is no ordinary wolf and would need a ‘sacred bullet’ to be killed.

With the soldiers comes salvation and the Englishman is returned to the hotel.

The story ends with a twist as both the protagonist and the reader discovers that the hotelier only sent out a search-party on receiving a telegram from a Count Dracula.

Differences between Dracula’s Guest and Dracula

It is tempting to read the unnamed Englishman as Jonathan Harker.

However, as many commentators have noted, the protagonist in ‘Dracula’s Guest’ is far braver than the timorous Harker.

Moreover whilst the opening date of the novel corresponds with the short story – Harker leaves Munich for Transylvania on the 1s May – the discovery of Stoker’s notes for Dracula suggest that the incidence with the wolf in the graveyard was shifted to different dates and ultimately was omitted from the novel entirely.

‘Dracula’s Guest’ can be read as a standalone story. And, yet, the ending of the narrative cannot work without the novel.

The name Dracula is eternally entwined with Stoker’s eponymous vampire. ‘Dracula’s Guest’, though a masterpiece of the Gothic in its own right, lives parasitically on Stoker’s most famous work.

Works cited: Bram Stoker, ‘Dracula’s Guest’, in Anne Williams (ed), Three Vampire Tales: Dracula, Carmilla and The Vampyre (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003), pp. 57-66.