Bram Stoker’s Dracula has inspired countless adaptations, often adding misconceptions not found in the original novel, from sunlight sensitivity to the iconic cape. CHRIS NEWTON, of the From The Page To Screen Podcast reveals the truth behind these Dracula myths

On the first three episodes of From Page to Scream Podcast, we took a deep dive into Bram Stoker’s Dracula, exploring the ways the original novel differs from the (many!) film adaptations.

I took this opportunity to look into the elements of Dracula Lore which have become fixed in the public mind despite the fact that you won’t find them in the book…

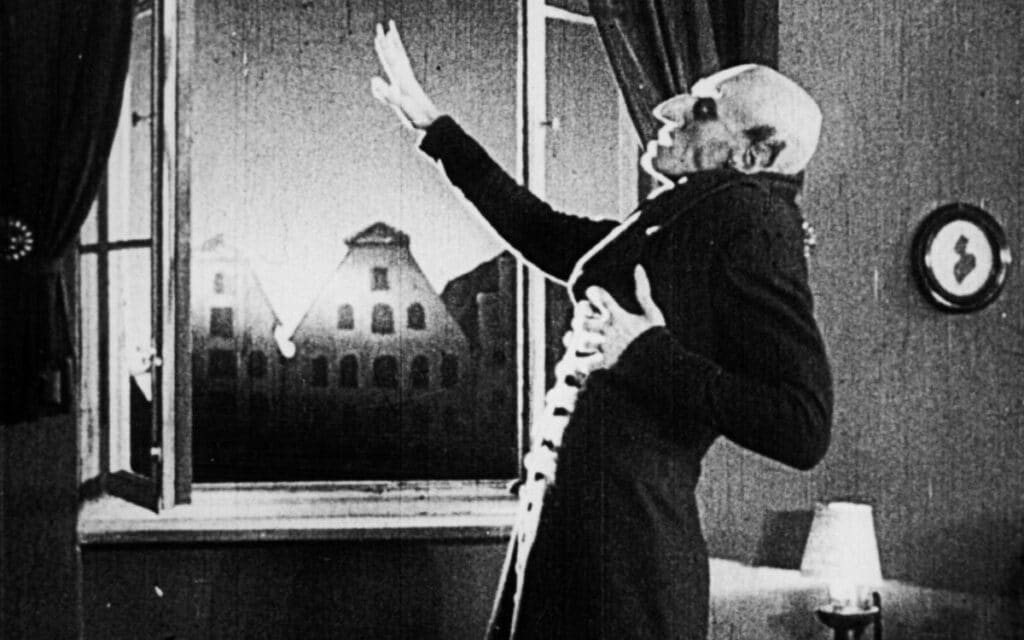

1. Death by Sunlight

In the original book, Dracula’s powers are stated to be weaker during daylight hours – he can’t shapeshift or turn himself into mist – but sunlight is not fatal to the Count.

As Stoker tells us: “His power ceases, as does that of all evil things, at the coming of the day. Only at certain times can he have limited freedom. If he be not at the place whither he is bound, he can only change himself at noon or at exact sunrise or sunset.”

Where Does it Come From?

The iconic image of Dracula reduced to ashes by the rising sun can be traced back to 1922’s Nosferatu. This was the unofficial German silent film adaptation ‘borrowed’ from Stoker’s story, and the iconic shot in which Count Dracula/Orlok (portrayed by Max Schreck) disappears in a puff of smoke after being tricked into feeding off Ellen/Mina and “forgetting the first crow of the cock”.

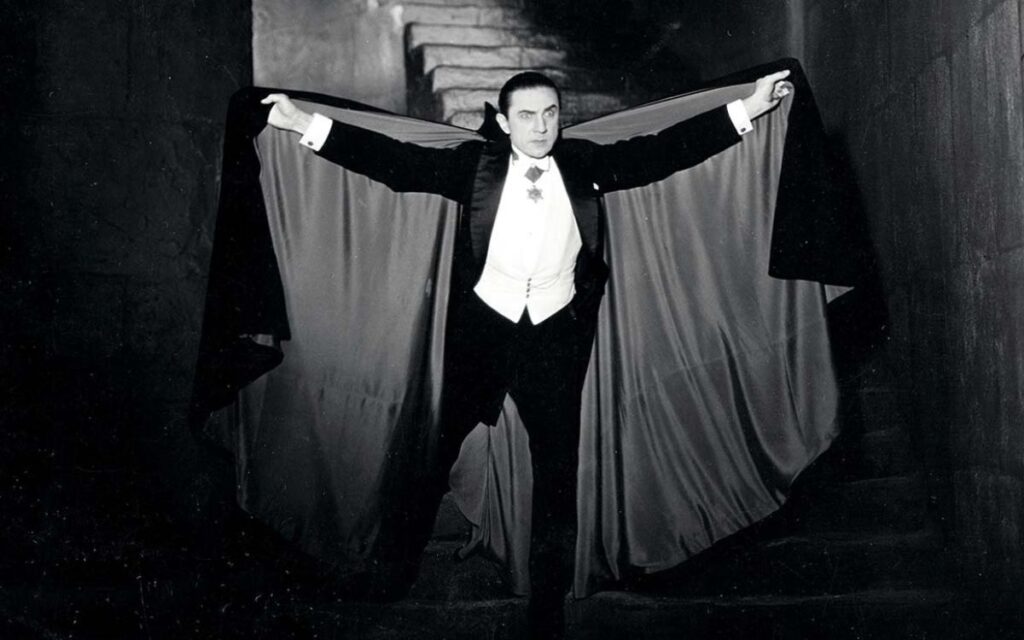

2. Dracula’s Cape

Surely, no vampiric Halloween costume would be complete without a floor-length black cape and over-sized collar? Yet, at no point in the book does Dracula wear a cape! Stoker merely describes him was being “clad in black from head to foot, without a single speck of colour about him anywhere”.

In the scene where Jonathan Harker spies the Count crawling down the walls of Castle Dracula, he is described as wearing a cloak which spreads “out around him like great wings” – but no cape.

Where Does it Come From?

The Count’s iconic cape can be traced back to the first stage adaptation of Dracula.

To achieve the effect of Dracula “disappearing”, the actor playing Dracula (one of whom was Bela Lugosi in his first major English-speaking role. Lugosi played his most famous character on Broadway before he starred in the legendary Universal movie!) covered himself with his cape.

The idea being that a trap door would open beneath the actor, who would slip out of sight, whilst the cape remained in place for a few moments before falling, giving the impression that Dracula had vanished in a puff of smoke.

However, his face was still visible during the illusion – so the pioneering wardrobe department came up with the large, up-turned collar – a garment now inescapably associated with Dracula – solely as a means to obscure the actor’s face! Necessity is the mother of invention.

Christopher Lee famously complained at the depiction of Dracula in an opera cloak in the Hammer version, scoffing at the notion that a Hungarian noble would wear such a thing.

But Bela Lugosi’s Count does visit the opera in the 1931 Dracula. We also know from Jonathan Harker’s visit to Castle Dracula that the Count is determined to blend into Victorian English society – so perhaps his wardrobe isn’t so much a deviation as Lee claimed. But then, who am I to argue with Christopher Lee?

3. Harker’s Predecessor

We all know that R.M Renfield, predecessor to Jonathan Harker turned lunatic zoophagous, inmate at Dr Seward’s asylum, was brought under the Count’s sway during his stay at Castle Dracula, right? Well… not according to Stoker!

According to the original text, we don’t really know who Renfield is, let alone how he came to be Dracula’s servant. Most of what we think we know about Renfield isn’t in the book at all.

Dr Seward’s phonograph records describe him as: “59. Sanguine temperament; great physical strength; morbidly excitable; periods of gloom, ending in some fixed idea which I cannot make out. I presume that the sanguine temperament itself and the disturbing influence end in a mentally-accomplished finish; a possibly dangerous man, probably dangerous if unselfish.”

Where Does it Come From?

In the Francis Ford Coppola movie, Renfield is directly implied to be a former employee of Peter Hawkins, who has returned from Transylvania as a bug eating madman.

Chances are that this concept of Renfield as a former solicitor come from the 1931 Universal movie starring Dwight Frye as Renfield. In this version of the story it is Renfield, not Harker, who visits Dracula in Transylvania to discuss the sale of Carfax Abbey. (Although, to further confuse matters, Renfield is an estate agent, not a solicitor, in this version.) Bela Lugosi’s Dracula hypnotises Renfield, and he returns to England aboard the Vesta (not the Demeter!) having lost his mind.

But before even Bela there was, of course, Nosferatu. In this unofficial adaptation, the “lunatic” character is named Knock. Before he is admitted to an insane asylum and starts picking flies out of thin air to feast upon, Knock is actually Harker’s (or “Hutter’s”) boss, whose correspondence from the Romanian Count comes daubed in sinister sigils, implying that Dracula is already exhorting some form of occult control over the estate agent.

4. The Vampire Lover

Since Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula adaptation in 1991, Dracula has invariably been portrayed as a romantic figure. Whilst there is undeniably something brooding and seductive about the character as written, Dracula is not a particularly romantic character. Certainly, his “relationship” with Mina Harker is drastically different as written. Far from crossing “oceans of time” to be with her, Stoker’s Dracula describes Mina as his “bountiful wine-press”!

Where Does it Come From?

It’s easy to point to Gary Oldman’s Dracula, who recognises Mina Harker as the reincarnation of his lost love, Elisabeta (again, not in the novel!) as the origin of the romantic Dracula.

However, it’s worth remembering that between Bram Stoker’s book and Francis Ford Coppola’s film came Anne Rice’s seminal Vampire Chronicles, which gave us the archetypal frilly cuffed, tortured romantic Vampires – specifically Louis and Lestat in Interview with the Vampire.

They left an indelible mark on the genre, and it seems inevitable that the next major screen reimagining of Dracula would depict the Count as more than a little Lestatesque.

But before Anne Rice, let’s not forget Christopher Lee. He played the character as an out and out villain, yet it’s interesting to consider the tagline for Hammer’s 1958 Dracula adaptation: “The terrifying lover who died – yet lived!”

Lee may not have brought sensitivity to the role, but he certainly brought sex appeal. Consider the scene in which Lucy takes delight in removing her cross and opening her windows as she waits for Dracula to enter.

5. The Reincarnated Bride

In Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation, Dracula is given a backstory in which his beloved wife leaps to her death from the walls of Castle Dracula, having been falsely informed that her husband was killed in battle by his Ottoman enemies. This idea of the reincarnated lover re-emerges in the Dracula 2013 TV series.

Where Does it Come From?

It’s easy to point to the Coppola film. As Dacre Stoker said in our interview with him on From Page to Scream, “the romantic side of the ’92 film was a needed change … love sells. When the 90s came around, if you’re going to put a vampire film on when other films could be showing risqué material and more violence, the vampire film had to be more than just boobs and blood. It had to have some substance to it. The love element had to be involved”.

Dacre is right, yet the concept does predate Coppola. In House of Dark Shadows (1970), the Vampire Barnabas Collins believes he has found a reincarnation of his long-lost fiancée, but in Love at First Bite (1979) it is Mina Harker herself who is the reincarnation of Dracula’s true love.

Even though it came six years after Love at First Bite, and isn’t a Dracula film, it’s impossible not to also consider Fright Night (1985). Charley’s Vampire neighbour, Jerry Dandrige, has a painting of his long-lost love who looks identical to Charley’s girlfriend, Amy, whom Jerry seduces and converts. It may not have been the first occurrence of this trope, but it certainly set a tone that Coppola was to follow.

6. Dracula versus Vlad the Impaler

Bram Stoker famously came across the name ‘Dracula’ in a library in Whitby, and his novel’s antagonist – “Count Vampyre” – had a new name.

The name comes from Vlad Dracula, also known as Vlad the Impaler (Vlad Tepes in Romanian), a former Voivode (ruler) of Wallachia.

Dracula literally means “son of the Dragon”, as Vlad Tepes’ father was known as Vlad Dracul (“Vlad the Dragon”) – so named because he belonged to “The Order of the Dragon” (a chivalric order established by the Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund, to fight the Turks.)

Like Vlad Tepes, Count Dracula is – or was – a Voivode who fort against the Turks but, as Dacre told us, Bram Stoker had almost certainly planned to set his vampire novel in Styria (a place already synonymous with vampires thanks to Sheridan le Fanu’s Carmilla – hence the Austrian word “vampire”), before discovering the name Dracula, “so he took a Wallachian Prince and simply moved him to Transylvania. He was a master of merging things; he merged characters and castles.”

Merging being the operative word. The name, and some of the character’s backstory, are the same, but Dracula was never intended to literally be Vlad Tepes.

What does Stoker say?

According to the Count himself: “[Dracula] inspired that other of his race who in a later age again and again brought his forces over the great river into Turkey-land; who, when he was beaten back, came again, and again, and again, though he had to come alone from the bloody field where his troops were being slaughtered, since he knew that he alone could ultimately triumph! They said that he thought only of himself. Bah! what good are peasants without a leader?

“Where ends the war without a brain and heart to conduct it? Again, when, after the battle of Mohács, we threw off the Hungarian yoke, we of the Dracula blood were amongst their leaders, for our spirit would not brook that we were not free. Ah, young sir, the Szekelys—and the Dracula as their heart’s blood, their brains, and their swords—can boast a record that mushroom growths like the Hapsburgs and the Romanoffs can never reach. The warlike days are over. Blood is too precious a thing in these days of dishonourable peace; and the glories of the great races are as a tale that is told.”

Where does it come from?

It’s an easy assumption to make given their shared name. Again, Francis Ford Coppola further cemented the connection by depicting his Dracula fighting against the Ottoman Empire and impaling his victims on spikes, but the link can once again be traced back to the original stage production by Irish actor and playwright Hamilton Deane, in which Van Helsing directly identifies Count Dracula as Vlad the Impaler.

I think it also comes from a desire simply to give Dracula a clear backstory; to explain him, just as other adaptations have presented him as what became of Judas, cursed to live on in un-death for his betrayal of Christ.

To me, any kind of “explanation” of Dracula is only detrimental to the character. Rather than a cursed disciple, or immortal warlord, Dracula – certainly as depicted in the novel – is an anthropomorphic personification of superstition itself.

He exists in “The Land Beyond the Forest”, where the dead travel fast and were, when the clock strikes midnight on the eve of St. George’s Day, all the evil things in the world have full sway. He is ancient, unknowable, and eternal. And even if he literally was Vlad Tepes (who was born around 1428), the fact that he was a Wallachian Prince would be far less remarkable or noteworthy than the fact that he was still alive in 1897!

You can hear more about Dracula, including From Page to Scream Podcast’s interview with Dacre Stoker, here: https://linktr.ee/frompagetoscreampod

Tell us your thoughts about these Dracula myths in the comments section below!