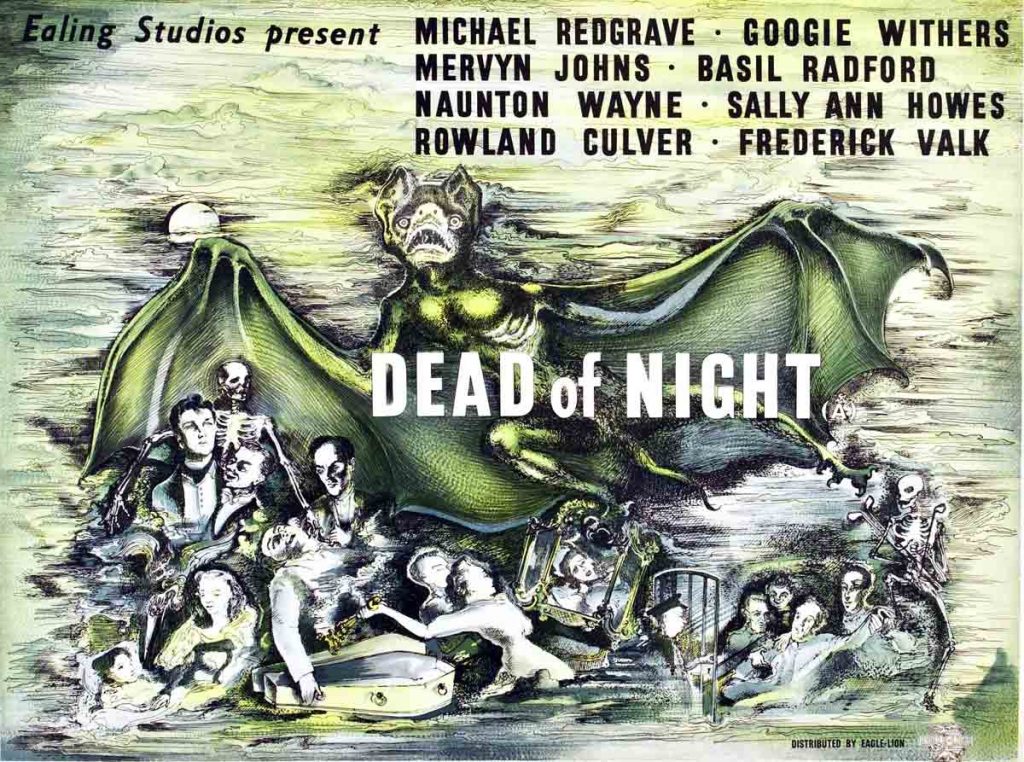

Guest writer JEZ CONOLLY, co-author of a new book about Dead of Night, tells us about the classic English horror Dead of Night (1945)

1. The film inspired the Big Bang Theory.

Astronomer Royal Sir Fred Hoyle and his Cambridge colleagues Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold were inspired by a viewing of Dead of Night when formulating their pre-Big Bang ‘Steady State’ theory of the Cosmos. ‘My God! It’s a cosmology. Maybe there’s something in this cyclical cosmology’ wrote Hoyle in his diary after witnessing the film’s famously elliptical narrative, and so was born a theory explaining life, the Universe and everything based on a horror film about one man’s never-ending nightmare.

2. Martin Scorsese rates it as one of his top horror films of all time.

Martin Scorsese put Dead of Night at number 5 in his ’11 Scariest Movies of All Time’ compiled for website The Daily Beast in 2009. He described it as ‘a British classic’ with a collection of tales that are ‘extremely disquieting, climaxing with a montage in which elements from all the stories converge in a crescendo of madness. It’s very playful… and then it gets under your skin’.

3. Dead of Night was made when the government was banning horror films.

Despite the pressure from government and censor to avoid the production of horrifying material during the war years it was quite common practice at the time for studios to submit scenarios for potential films of a disturbing nature to the British Board of Film Censors for assessment. In the months before Dead of Night Ealing submitted a number of ideas for future films that, thanks to the negative reception from the BBFC, failed to see the light of day. These included The Anatomist, a tale about a surgeon associate of Burke and Hare, Uncle Harry, concerning a poisoner, and The Interloper, an adaptation of the 1927 Francis Beeding novel The House of Dr Edwardes which in diluted form would later become Hitchcock’s Spellbound. If the censor’s decisions had been different Dead of Night may not now be regarded as quite such a singular work of the macabre from the period.

4. The film has links to J.B. Priestley, the author of The Old Dark House (1932).

Thematically and tonally the premise of ‘Linking Narrative’, the framing story that joins together the film’s five separate episodes, is reminiscent of J.B. Priestley’s ‘Time Plays’, a series of theatrical works written by the playwright between the early 1930s and the mid-1940s that are linked by their exploration of different temporal phenomena. The first of these, ‘Dangerous Corner’ (1932), concerns a party at a country house during which a chance remark triggers a series of revelations. This disclosure of the various characters’ dark secrets is erased when the play ends by returning to its opening scene, identical save for the chance remark which this time goes unsaid, resulting in the ‘dangerous corner’ being avoided. The more celebrated ‘Time and the Conways’ (1937), in its telling of the fate of a family in the two decades after the First World War, has a similar rerun of its beginning at its end. Another of the plays, ‘I Have Been Here Before’ (1937), as the title suggests, deals with the implications of déjà vu.

5. The story also has links to Series One of True Detective, starring Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson.

There’s a link between Dead of Night and series 1 of True Detective. The Hearse Driver episode in the film is based on E.F. Benson’s short story ‘The Room in the Tower’ published in 1912, which was itself inspired by a popular urban myth of the time concerning Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, whose life was purportedly saved by the vision of a coffin-carrying ghost. The American author Robert W. Chambers was similarly influenced by the myth when writing ‘The Yellow Sign’, one of the stories that comprised his 1895 work The King in Yellow, a book of short stories that were repeatedly referenced in True Detective.

6. The Christmas Party was based on a real life murder.

The Christmas Party episode was the only story based on real life events, specifically the Constance Kent murder case of 1860. After being convicted of the murder of her half-brother Francis, Constance Kent served 20 years in prison before being granted release in 1881. She emigrated to Australia in 1886 where she lived out the rest of her life. She very nearly lived long enough to see Dead of Night, dying on the 10th of April 1944 at the age of 100.

7. Sally Ann Howes, who played “Sally O’Hara” in the Christmas party episode, had real-life ESP.

Sally Ann Howes appears to be the only cast member to have experienced something akin to the supernatural events depicted in the film. There are claims attributed to her which suggest she possessed Extra Sensory Perception and on several occasions in her life she had pre-knowledge of the imminent death or hospitalization of friends and loved ones. The most notable occasion came in 1956 when her fiancé, the society photographer Sterling Henry Nahum, known as ‘Baron’, was admitted to hospital for a routine hip operation but died unexpectedly shortly afterwards from complications. Soon after a visit to the hospital, when all seemed well, Sally Ann knew, as though it were written, that her husband-to-be was going to die.

8. Alfred Hitchcock found inspiration in Dead of Night’s final scene for Psycho (1960).

You will find inspiration for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho in Dead of Night. In relation to the Haunted Mirror episode, there are echoes of the Divided Self theme in a number of Hitchcock’s films, especially in Psycho, a film that is famously replete with meaningful mirrors. The similarities between Psycho and the Ventriloquist’s Dummy episode are even more striking. The protagonist of the episode, ventriloquist Maxwell Frere (Michael Redgrave) and Psycho’s Norman Bates both articulate a distrust of psychiatry. In Psycho we last see Norman Bates in a cell, wrapped in a blanket and completely consumed by the ‘Mother’ part of his personality. He looks up and briefly we see the bared teeth and hollow eye sockets of Mrs. Bates’ preserved corpse superimposed over Norman’s features. Our last sight of Maxwell Frere is in his sanatorium bed, speaking in his dummy Hugo’s voice, an image that dissolves to leave just his eyes, large and fixed, denoting the final victory of his Hugo half.

9. The song ‘The Hullalooba’ has an interesting backstory of its own.

The song ‘The Hullalooba’, performed during the Ventriloquist’s Dummy episode, combined the talents of two important female artistes. It was composed by French singer-songwriter Anna Marly; born into Russian aristocracy, Marly spent her early life in France before moving to Britain to escape the German occupation. She was a leading supporter of the Free French movement and famously penned the resistance anthem ‘Chant des Partisans’. Marly was named a Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur in 1985. Elizabeth Welch, who performed the song in the film was best known for her songs ‘Stormy Weather’ and ‘Love for Sale’. Welch has come to be recognised as an important figure in the advancement of African American culture in the twentieth century. The recipient of numerous awards and accolades in later life, Elizabeth Welch died at the age of 99 in 2003.

10. Noel Coward may have influenced the Michael Redgrave’s Ventriloquist’s Dummy Episode.

A possible source of inspiration for Michael Redgrave’s performance and characterisation in the Ventriloquist’s Dummy episode could have been Noel Coward, with whom Redgrave had a relationship that started in 1941. In the mid-1930s Coward saw American ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s act with his dummy ‘Charlie’ at a party given by the socialite Elsa Maxwell, during Bergen’s break out of Vaudeville into the supper club circuit at Chez Paree in Chicago. It was on Coward’s recommendation that Bergen won his next booking, in Manhattan, leading to his future fame and success. Bergen had chosen to dress himself and Charlie in white tie and tails when making the transition from Vaudeville. Combined with the dominant and hostile turn by the ebullient Charlie, Bergen’s shy personality and the proximity of the club’s name ‘Chez Paree’ to the Paris-located ‘Chez Beulah’ in the film, it is tempting to see this story passing from Coward to Redgrave and into the film itself.

Buy Dead of Night (Devil’s Advocates) by Jez Conolly and David Owain Bates now from Amazon

JEZ CONOLLY is co-editor, with Caroline Whelan, of three books in the World Film Locations series (Dublin, Reykjavik and Liverpool) published by Intellect. He writes regularly for The Big Picture magazine and website and has contributed to numerous other cinema books and journals. His previous book in the Devil’s Advocates series concerned John Carpenter’s The Thing. Jez is Head of Student Engagement with University of Bristol Library Services.