MATTHEW E. BANKS explores Charlotte Dymond’s murder in 1844 on Bodmin Moor, and whether the man hanged for it was falsely accused

Bodmin Moor. Bleak, desolate, isolated. A landscape that is dominated by Roughtor and Brown Willy, where the sun can shine one moment then heavy rain, fog and mists the next. A few wild birds fly in the sky above. It is a place of mystery, legend and myth. Where a giant black cat is said to wander and where Tregeagle is chased by the Devil Himself. The moor is a lonely place and is said amongst others to be haunted by the ghost of a young girl who was savagely, brutally murdered.

For nearly two hundred years the ghost of Charlotte Dymond is said to have walked the moors in search of something or someone. Speculation is that she is looking for her lover, Matthew Weekes, who was executed at Bodmin Gaol for her murder. Many now believe him to be innocent of the crime.

Jealousy was said to be the reason behind it as it was rumoured that Charlotte fancied another. That reason stood for 150 years, until 1978 when Cornish author and Bard Pat Munn released her book The Charlotte Dymond Murder Bodmin 1844 in which she not only questioned the validity of the case and why the defence did not defend Weekes to the best of their ability, why witnesses were not cross-examined and why a man was allowed to die for a crime that he may not have committed. Munn even offered up another account of what may have occurred, which was not murder, but suicide!

Who was Charlotte Dymond?

Both Charlotte Dymond and for seven years, Matthew Weekes, worked at Penhale Farm for a widow, Mrs Phillipa Peter. She ran the farm with her ‘soft’ son John, a servant John Stevens, and another unknown person. Mrs Peter was born of the Cornish gentry having been born a Billing and was surrounded by family connections with nearly all those connected to the case in some way or another.

Despite his loyalty, Matthew Weekes was the outsider, considered to be above his station because of how he dressed and was not liked because of his abrasive attitude towards others. He was also a cripple, walking with a distinctive limp, missing most of his teeth, his face heavily pockmarked and was a ‘simpleton.’ He was an unlikely suitor for Charlotte Dymond.

On March 25th 1844 Mrs Peter hired John Stevens to work at the farm and she terminated Charlotte’s employment. As to why she was still at the farm three weeks later is open to conjecture. At Weekes’ trial Mrs Peter was never questioned about this, nor was she brought up on obvious discrepancies in her testimony.

On April 14th 1844, these two young lovers embarked on a walk – a walk where one would return and the other would vanish for seven days, only to be found with her neck ripped open, dead eyes staring silently into the sky, revealing nothing of what had transpired. Charlotte Dymond, the daughter of a Tresparrett schoolmistress and a Poundstock butcher was 18 when she was murdered. Despite being a third generation base child she was well educated and could read and write.

Matthew Weekes’ ghost haunts Bodmin Gaol

Matthew Weekes, a crippled simpleton was 23 when he was hanged. His spirit is said to haunt Bodmin Gaol, unable to rest because he was innocent, while Charlotte’s wanders the moors and the church where her body is buried.

The reason given for the murder was that Matthew Weekes was jealous of the attention that Charlotte Dymond paid to Mrs Peter’s nephew, Thomas Prout. This information came from one witness and one witness only, and that was Mrs Peter herself, though she failed at trial to mention that Prout was her nephew.

No other witness mentioned this and her word was taken as final. This was the power of her social standing in the local community. Nor is it ever questioned as to why Mrs Peter waited nine days before ordering a search for Charlotte. Despite knowing that April 14th was damp, rainy and foggy; and knowing that the moor is treacherous in this type of weather, Phillipa Peter waited!

During those nine days, Matthew Weekes was continually interrogated as to the whereabouts of Charlotte, and he repeated the same story to everyone, that she had gone to another farm for employment. It got too much for him and he left the farm and went to Plymouth, to see his sister, which is where he was arrested.

What of Thomas Prout, Charlotte’s alleged suitor? He and Weekes had a history of disagreement and did not like each other. When John Stevens goaded Weekes that he’d lose his girlfriend to Prout when he came to work at the farm, Weekes retorted that if Prout did come to work at the farm, then he would leave. Prout himself baited Weekes that he would take Charlotte off of him, should he so choose too and the retort that Weekes gave led to his being reprimanded by his employer.

On the morning of April 14th Prout was at Penhale Farm, when Charlotte received a letter of employment and alleged at the trial that she had made an arrangement to meet him at Davidstow church at 6pm, but did not keep said date. As the first person to realise that there was something wrong, why did he not raise the alarm? Surely any ‘normal’ person would have gone to the farm to find out what had happened. Prout just vanished into the ether until the time of the inquest.

The validity of his testimony was not cross examined at either the inquest or trial, nor was the question raised to how he did not join in the search for her when other family members did? We can only speculate the answers to these questions, but what is certain is that he was named as the reason for Dymond’s murder with the release of the original confession.

This original confession: “He (Weekes) declares that it was not a premeditated act, but that when on the moors she stated to him that she was fonder of Prout than of him, and he then says that upon her telling him this he was seized with a sudden impulse that he would never allow her to have any other than himself, and he then cut her throat.” This was published in The Times on August 8th, four days before Weekes was due to be executed and this was republished in several other newspapers before the ‘official’ confession was released after the said execution.

There would be no escape for Prout as eyes once friendly now looked at him accusingly, especially when the monument was erected on Friday June 13th 1845 and re-opened old wounds. 20 months after Dymond was murdered and 16 months after Weekes was executed, Thomas Prout was dead at 32. He is buried in an unmarked grave at Davidstow Church and its whereabouts are unknown.

The legacy of the Charlotte Dymond murder

Even now, after nearly two centuries, local people do not like to discuss the case.

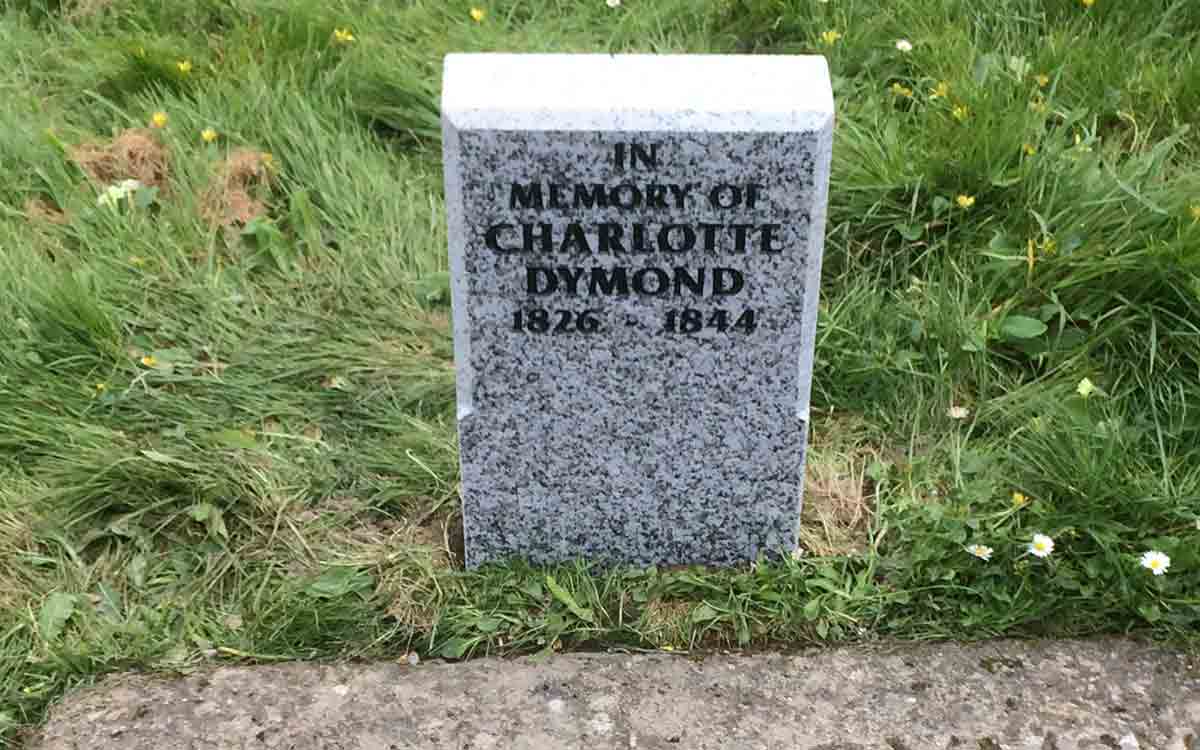

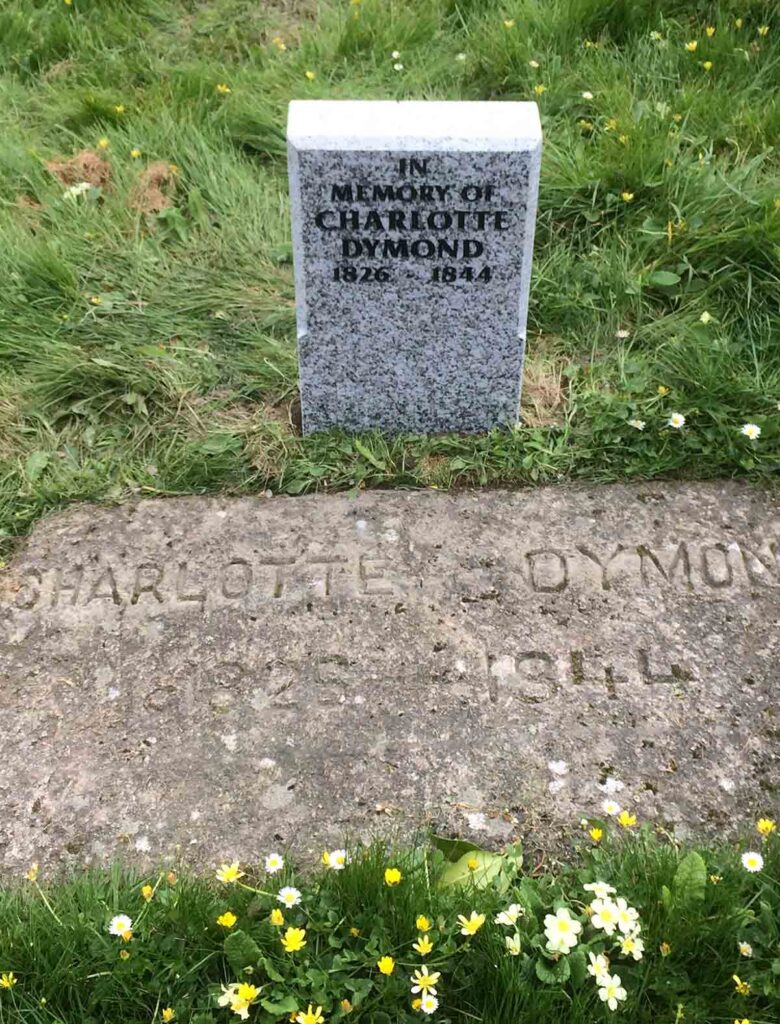

There is a stone monument on the moor, close to where her body was found. It was erected fourteen months after her murder and ten months after Weekes’ hanging. It originally stood on the site where her body lay, but time and the elements took their toll and it fell down. It was re-erected in 1888 on more secure ground under the instruction of the Reverend A H Malan.

The first reported case of a ghost was in 1932, eighty eight years after the murder, when B.C. Spooner wrote, “A figure of a woman is seen on BrownWillie, looking over the moors, as one approaches. But when one gets nearer or goes around the other side of Brown Willie, there is no woman there,” and he goes on to state, “There is no history of the ghost.” It would not be for another seventeen years until the ghost was given a name and history.

In 1949 Cornish historian William Henry Paynter wrote and published an article titled, The Murder of Charlotte Dymond and Subsequent Appearance of her Ghost.

In his essay he chronicles the story of the old Volunteers that had a camp on the moor and of how it they had difficulty in keeping sentries posted at night, for one had seen the ghost of Charlotte wandering the moor or of the story of the tourist who went fishing one day and on his return to his hotel, commented to the proprietor on the remoteness of the moors, having only seen wandering ponies, sheep and a young solitary girl wandering across the moor, stopping every so often, shading her eyes as though she were looking for someone.

He was asked to give a description of the girl, which he duly did, only to be told, “You have seen the ghost of Charlotte Dymond [ ]” Paynter went on to give talks and lectures about the case which were highly influential on Charles Causley, the Cornish Poet, who in 1958 published The Ballad of Charlotte Dymond. This poem is now part of the Secondary school curriculum.

Paynter was to raise Charlotte’s ghost again in 1967, in an article titled, A Moorland Murder: A Cornish Romance which ended in Tragedy. In this article he recounts the facts as in his previous article, but the number of Volunteer sentries had grown from ‘one’ to ‘some’ that had seen the ghost. In the eighteen years between these two articles, there appears to be no ‘new’ sightings of the ghost!

It is with the 1970s onwards that Charlotte’s ghost firmly took root in the public imagination, with authors such as James Turner, Michael Williams, Alan Neal all writing articles about her and of course the publication of the late Pat Munn’s book. In her book, Munn relates Paynter’s history of the ghost; she also relates to some experiences that she herself had whilst writing her book. She states that a ‘large white window-sill in my bathroom turned bright pink’ on at least three occasions and that her husband had items that would disappear, only to re-appear later.

It has been claimed that workers at the Stannon Clay Works which is situated near the moor have seen the ghost of Charlotte, whilst other witnesses have claimed a meeting with her at twilight at Davidstow graveyard, where she is buried. She is said to have curtseyed and whispered, ‘Good evening.’ On that journey that was taken nearly two hundred years ago, people have now reported hearing a strange un-nerving girl’s laughter near to where Weekes claims to have left Charlotte, and in the same voice says, “I don’t want you to come any further. Go home!”

Charlotte Dymond is buried in hallowed ground, although her grave was unmarked until 1875, when a broken cross from the eastern gable was placed to mark it. Unlike others that were hanged and buried in lime to the side of the main prison, Matthew Weekes is buried under cold granite by the old coal chutes. When his coffin was lowered into the grave, it floated as it was filled with water.

Was Matthew Weekes guilty or is he innocent – looking at the case through modern eyes, the likeliness is that he was innocent – the last sighting of Charlotte was around 7pm that Sunday night talking with someone, (the witness was originally unable / unwilling to name Weekes as the man on the moor) – So we are asked to believe that this crippled simpleton was able to murder his girlfriend in the most horrendous way, without getting any blood on him, then disperse of her body, before walking back to Lower Penhale farm and have a conversation with his employer before going to bed, all in the space of an hour and a half!

Is the monument on the moor holding Charlotte’s spirit earthbound? Is the epitaph upon it incorrect and that Weekes was innocent, and she cannot rest until he is cleared? Did her murderer escape justice? Only Charlotte knows these secrets and perhaps one day the truth of the case will finally be solved, and Charlotte can then rest in peace.

From 1844 to 1875 Charlotte’s grave was left unmarked. From 1875 to 2001 the grave was marked with a broken cross. In 2001 a memorial stone (formerly a farm doorstep) was laid with the inscription ‘Charlotte Dymond – 1828 – 1844. On June 18th 2017, Charlotte Dymond finally got a proper headstone with a dedication service, after a concert by a group of musicians requested that the proceeds be donated towards a proper headstone for her.

Footnote: It is interesting to note that both the Lightfoot murder case of 1840 and the Benjamin Ellison murder case of 1845 both have contemporary illustrations of the accused, yet there is no contemporary newspaper illustration for Matthew Weekes (that I have been able to find.)