JIM IVERS takes a look at Carmilla films inspired by J. Sheridan LeFau’s vampire classic

Twenty-five years before Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”, Irish writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu published “Carmilla” (1872), a gothic vampire novella.

It tells the story of a young woman’s susceptibility to the attentions of a female vampire named Carmilla. A strong lesbian attraction is at the heart of the story, but this is depicted in a subtle, restrained manner typical of Victorian era literature.

Various characters and incidents had a direct influence on the writing of Stoker’s “Dracula”.

And soon after the then-shocking 1931 “Dracula” film landed in theaters, a series of gothic movies based on “Carmilla” began as well. What follows is a brief study of that film cycle.

Vampyr (1932)

This French-German production Vampyr from Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer was filmed in 1930-31.

Loosely adapted from “Carmilla” and another Le Fanu short story, this has no lesbianism or even much overt vampirism.

Here the vampire is an old witch-like crone who drifts in and out of the story like a ghost. This is a bizarre, dream-like tale of apparitions, living shadows, and occult horror.

It seems to have more in common with the surreal Buñuel/Dali collaboration “Un Chien Andalou” (1929) than a conventional movie.

The result is a fascinating European art film that annoyed critics and confused audiences in 1932.

Dreyer was a master of experimental camera and editing techniques that reached a high level of sophistication in the last years of the silent era.

Sadly, most of what had been learned in filmmaking was discarded (or at least put on hold) during the clumsy transition to talkies (1929-1931).

Sound was first recorded live, with noisy cameras locked-down inside sound-proof boxes and inert actors hovering around microphones concealed behind flower pots and other props.

It was a giant leap backward to the days of filming stage plays, circa 1900.

However, the technology for adding post-production sound was gradually being developed.

Dreyer shot “Vampyr” as a silent film, which gave him more creative freedom. A sound track with dialog, sound effects, and music was added later.

The film is full of clever visual tricks to create a mood of supernatural menace.

Ghosts take the form of shadows dancing along a white-washed wall.

Reverse film and double exposures are used to great effect.

The main character falls asleep and his spirit, a semi-transparent ghost body, rises up and wanders off.

During this ghostly perambulation he watches his physical body being sealed in a coffin with a glass window.

We then see his point of view from inside the coffin looking up at the trees and buildings as he’s carried to the cemetery.

The conventionally-filmed “Dracula”, besides some nicely atmospheric opening scenes, is mostly talky, static scenarios lacking visual interest.

By contrast, “Vampyr” is full of novelty, variety, and a persistent atmosphere of strangeness.

Both films end with a staking-the-vampire scene. The overly squeamish “Dracula” disappoints with an off-camera groan.

“Vampyr” shows the vampire’s body transform into a hideous skeleton.

The best way to view this film is Criterion’s 2008 DVD release. This pristine, restored version comes in a 2-disc set that’s loaded with bonus features.

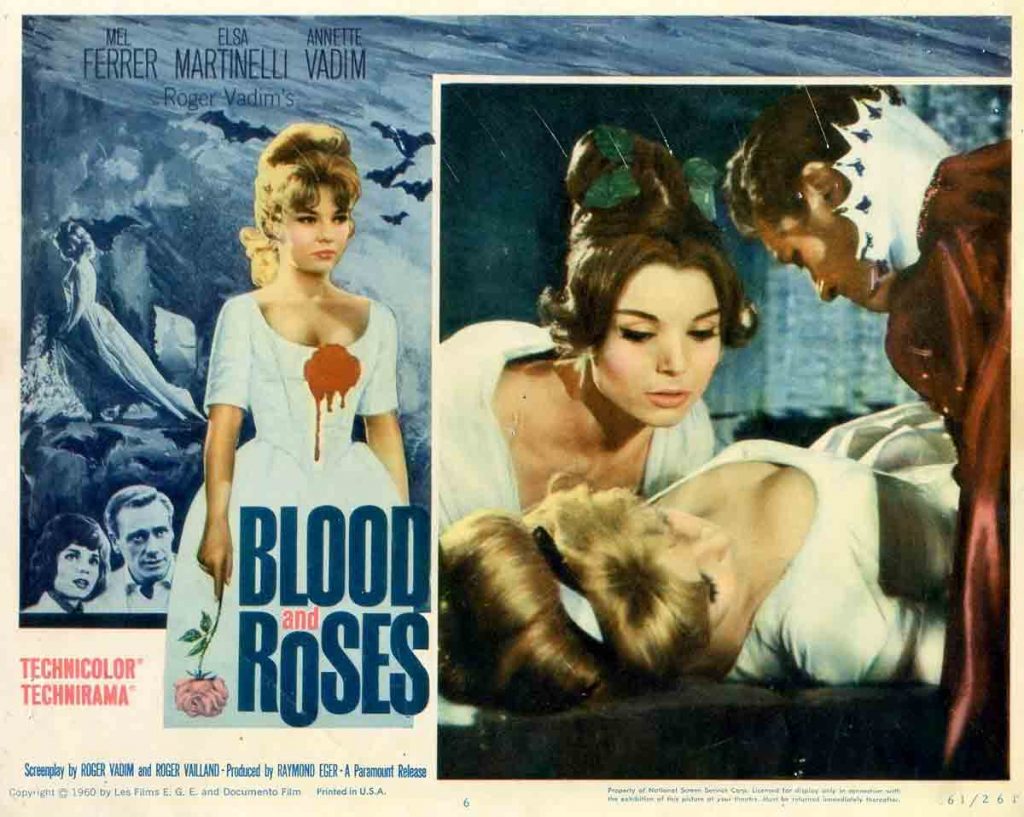

Blood and Roses (France, 1960)

Set in the present, young Carmilla is jealous of her friend’s engagement, and her obsession leads her to the tomb of a female vampire.

The vampire possesses her and leads her to kill and terrorize the inhabitants of the estate. But is it all in her mind, or is she really under the control of an ancient vampire ancestor?

Probably Roger Vadim’s best film. Stylishly photographed in vivid color, this has an extended dream sequence shot in black and white (with splashes of red blood added in).

An infuriatingly difficult film to find, it appears the only release was on VHS in the ’90s by Paramount.

Have only been able to view the trailer and excerpts on YouTube. And, what I’ve seen looks great.

The film is highly regarded and has something of a cult following. There must be some legal snag preventing its release on DVD.

Crypt of the Vampire aka Terror in the Crypt (Italty, 1964)

Directed by Camillo Mastrocinque (using his Thomas Miller alias). He also made “An Angel for Satan” (1966) with Barbara Steele.

Like so many Italian Gothic horror films, this is a ghost story involving a spooky old castle and a centuries-old curse.

There is next to nothing about vampires and just a few story elements taken from “Carmilla”. This also seems to have been partly inspired by the short story “The Mysterious Stranger” (1860).

Christopher Lee stars as Count Ludwig Karnstein. By this time Lee had relocated to Switzerland (for tax reasons) and was making mostly Italian and German films. (Hammer had failed to recognize his potential and was giving him mostly thankless supporting roles until his 1966 return as Dracula.)

Count Karnstein fears his daughter Laura has become possessed by a witch who was put to death by his ancestors 200 years previously, and who had sworn to take vengeance on the family’s descendants. (Laura has had a series of surreal nightmares.)

He hires a young antiquarian to research the family records and find a portrait or description of the witch (although I’m not sure what that will prove).

For some unknown reason, Laura’s nanny Rowena (who just happens to be a mistress of the occult) takes Laura to a secret room used for Satanic rituals.

Somewhat racy for 1964, the ceremony requires Laura to lie naked face down across a large pentagram on the floor (she is partly covered by some cloth).

Rowena invokes Satan and the spirit of the dead witch so she can confirm that Laura is not possessed. (Never mind that this makes no logical sense.) We see the witch (but not her face) being condemned to death in a flashback scene as she speaks through Laura.

When a carriage breaks down outside the castle, the beautiful Carmilla character (here re-named “Luba” for some reason) becomes a guest for a few days. Laura and Luba immediately become infatuated with each other.

The lesbian attraction is depicted (including a nicely executed dream sequence) by hand holding, kissing, and longing looks. At one point Laura leaves bite marks on Luba’s throat, but they are gone the next day.

In this story, the village of Karnstein, not the castle, has fallen into a picturesque ruin.

A dead man with one hand missing is found hanging in the bell tower of the abandoned chapel. In a particularly eerie scene, Rowena walks about holding the severed claw-like hand (candles burning on each fingertip) calling on Satan to identify the killer.

A wonderfully creepy sequence you won’t find in a U.S. or U.K. film of this period.

Despite some unexplained details and lapses in logic, the film compensates with consistently rich imagery and mood. This is in the same category (but not on the same artistic level) as “Black Sunday” and “Castle of Blood”.

The Italian film-makers in this era of black-and-white horror were the masters at creating a tense, gothic atmosphere with dramatic lighting, deep shadows, fluid cinematography, and haunting music.

They also had a flair for the supernatural, infused with a dreamy surrealism and eroticism that is quite unique.

The Hammer Carmilla films / Karnstein Trilogy

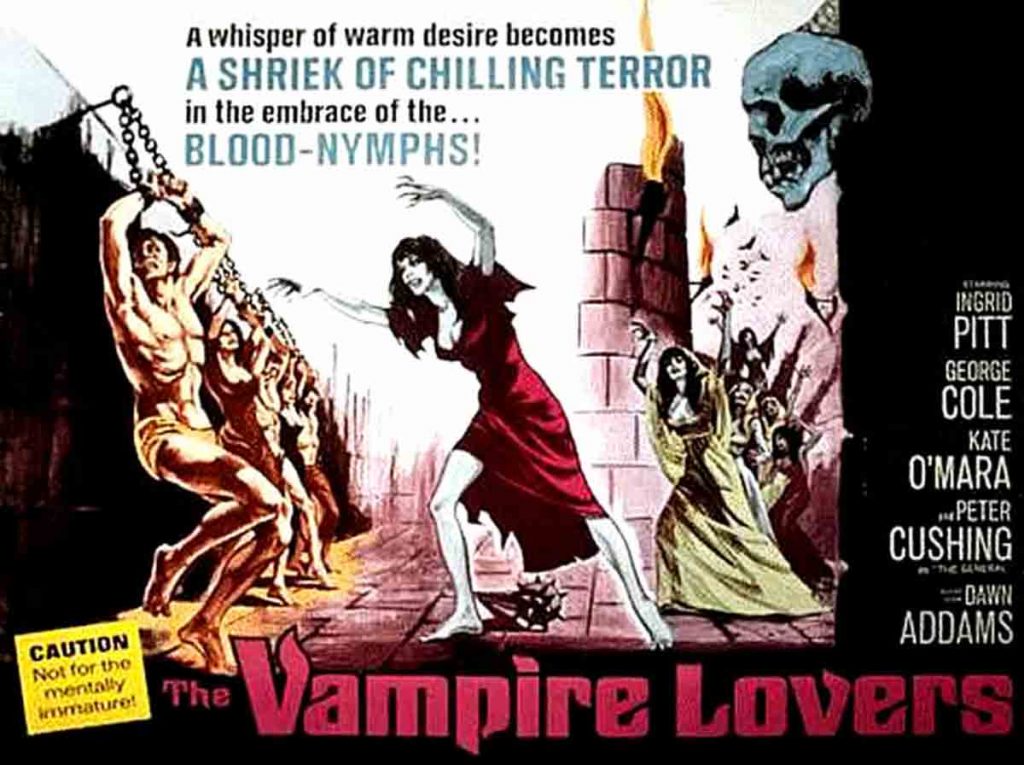

The Vampire Lovers (UK, 1970)

Hammer Films was on the brink of bankruptcy for the umpteenth time and desperately needed a hit.

This co-production with American International Pictures was a big critical and commercial success that saved the studio. It’s also one of their better films due to a cohesive story that moves forward with a sense of purpose.

Hammer’s novel adaptations (such as the excellent “The Devil’s Rides Out” aka “The Devil’s Bride in the US) are generally superior. Their original screenplays (for Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, et al.) tend to be slowly-paced with meandering subplots and melodramatic elements that weaken the story.

This was also the first big plunge into the erotic horror genre for the traditionally conservative studio. An R-rated film with (gasp) nudity and lesbianism, however subtle, was considered a shocking departure at the time.

The director used the old trick of shooting additional scenes with extra-racy content to distract the censors from cutting the scenes he wanted left in.

As for production, Hammer was brilliant at making low-budget films that never looked shoddy. A mix of actual locations and elegant sets plus beautiful period costumes (most of their films are set in the 19th century) photographed in vivid color created a rich, classy ambience rarely seen in horror films.

Exotic Polish actress Ingrid Pitt was a perfect choice for Carmilla. She brings a sense of mystery and a seductive, feline power that jumps off the screen. She also gives the character an element of pathos. Her Carmilla is a reluctant vampire with feelings of affection and sadness for her victims.

The story begins in 1794 with a prologue narrated by Baron Hartog. He slays a family of vampires living in the ruins of Karnstein castle, but fails to find the coffin of the daughter, Mircalla (who died in 1546).

Cut to 20 years later (1814), the seductive “Marcilla” (Ingrid Pitt) with a woman claiming to be her mother, dances at a fancy ball given by General Spielsdorf (Peter Cushing).

A creepy man with a black hat and cape, obviously another vampire, arrives with news that takes the mother away so Marcilla is forced to stay with the General’s family – and his beautiful daughter, Laura.

This mysterious vampire in the black hat pops up repeatedly, lurking about on his horse in the darkness. He plays no role in the story and has no lines. He simply observes from afar, right up to the last scene. This character is never explained, which I found annoying. (We can assume he is Count Karnstein, Mircalla’s father.) Apparently the screenwriter added him as a possible carry-over in the event of a sequel.

Marcilla seduces Laura with her hypnotic gaze and draws small amounts of blood from her neck. Laura becomes anemic and gradually weakens and dies. Marcilla then vanishes and reappears as Carmilla, traveling with her “aunt”.

As in “Crypt of the Vampire”, their carriage breaks down. The aunt talks a count who happens along into letting Carmilla stay at his estate for a while. This is the last we see of the mother/aunt character. Who she is and where she goes is never explained.

As before, Carmilla seduces The count’s daughter, Emma, a voluptuous, doe-eyed innocent played by gorgeous Madeleine Smith. (The original story also repeats the same scenario twice.)

But Carmilla falls passionately in love with her. She draws blood from Emma’s neck but can’t bear to let her die. She wants them to live together as vampires. Their nude scenes are filmed in an extremely restrained, non-exploitive manner. It’s more art film than horror-erotica.

During this time Hammer was highly dependent on the earnings from its popular Dracula films. It is interesting that “The Vampire Lovers” presents an entirely different set of rules regarding established vampire lore.

Carmilla can go about during the day provided she avoids direct sunlight (and in some cases she doesn’t). She casts a reflection on water, does not turn into a bat, and sleeps in a burial shroud, not on a layer of soil from her homeland.

And in a very peculiar scene, she makes herself disappear when a cross-shaped dagger is tossed at her.

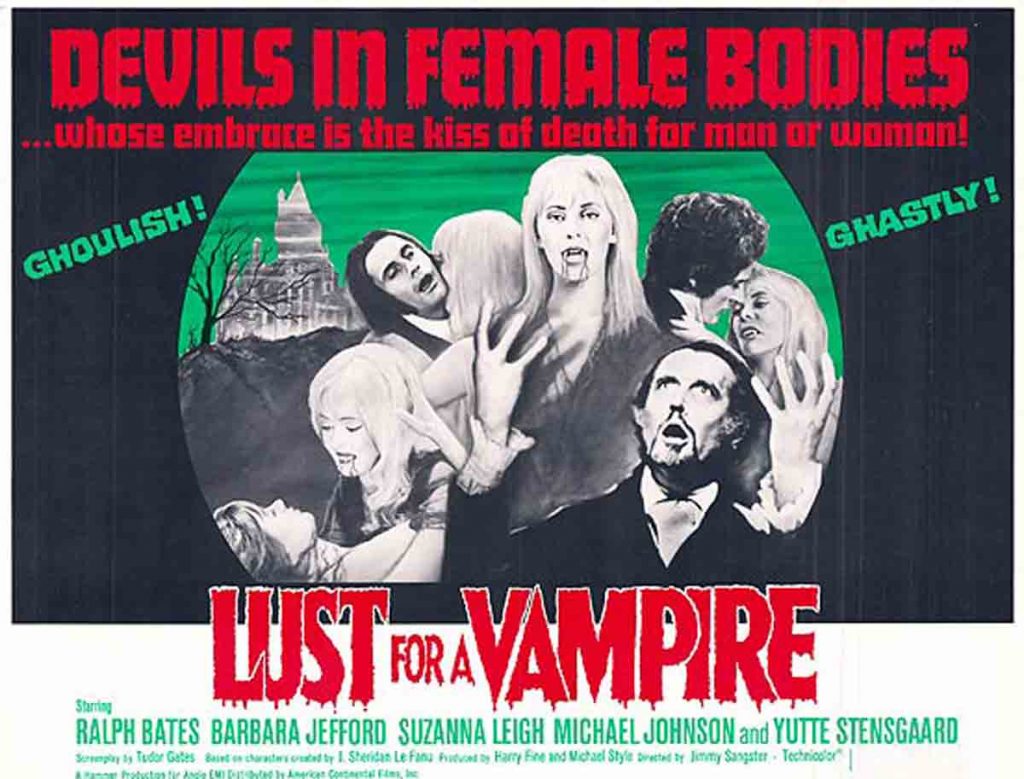

Lust for a Vampire (UK, 1971)

“The Vampire Lovers” was one of Hammer’s biggest hits. The studio wasted no time in putting this loosely related sequel into production. Instead of a literary influence, this has more of a pulp-fiction quality.

And, due to a temporary change in management, more sex and nudity than any other Hammer production. (Still, this film is fairly conservative compared to what was being churned out in France, Italy, and the U.S.)

Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster directed. He wrote many scripts (some good, some bad) for Hammer but only directed three features. And his inexperience really shows. This movie is plagued by a series of irritating and inept touches that could, and should, have been edited out.

Ingrid Pitt turned down the lead role and made “Countess Dracula” instead. The part of Mircalla Herritzen/Carmilla Karnstein went to Danish knockout Yutte Stensgaard. An ash blonde with captivating big blue eyes, this was a departure from the dark, smoldering sensuality embodied by Pitt. Stensgaard radiated a childlike naivete that gave her a soft, ethereal eroticism. Her seduction scenes have a dreamy, hypnotic quality.

The only bit of creative acting comes from the top-billed Ralph Bates (who starred in “The Horror of Frankenstein” also directed by Sangster). He usually played the handsome swain or charming-but-sinister aristocrat types. Here, Bates is quite amusing playing against type as a creepy, bookworm history teacher with wire-rim glasses and slicked-down hair. The role was originally written for Peter Cushing but he dropped out of the production due to the illness of his wife.

The mysterious “man in the shadows” from the previous film returns, more or less, billed as Count Karnstein and played by a different actor.

Well-known radio DJ Mike Raven was chosen, undoubtedly because he’s a dead ringer for Christopher Lee. (His voice was even dubbed to sound more like Lee.) Looking like a poor man’s Dracula, he performs a satanic ritual, pouring blood onto the shrouded skeleton of Carmilla. There are even closeups of Lee’s bloodshot eyes spliced in from a previous Dracula film. After some disappointingly hokey special effects, a nude, blood-drenched Stensgaard arises from the coffin.

Once again, the Count character lurks about, observing all the key scenes from a distance. Whenever someone is killed there is a corny zoom-in or jump cut to the smirking Count skulking about in the bushes. These added bits are unnecessary and increasingly ridiculous. The Count even steps in to kill a police inspector and impersonates a doctor in one scene (which is also rather silly). Also, this time the various vampires have no problem moving about in broad daylight.

The story is set in 1830, forty years after the last sighting of the Karnsteins (who haunt the village every four decades, we are told). The same castle ruins sets are used again. Carmilla’s crypt inscription now reads 1868-1710. A bit confusing as these dates contradict the timeline of the first film set in 1814. Instead of a sequel, this is really a remake that pretends the previous story never happened.

A dashing young writer, Lestrange (Michael Johnson), hears about the Karnstein legend and explores the ruins of the castle. During this, a highly annoying voice-over is inserted that needlessly repeats dialog from the previous scene (as if the audience was too dumb to remember) with a cliche echo effect. An archaic, clumsy, and rather insulting device.

In a plot turn straight out of a bawdy sex comedy, Lestrange happens upon an isolated girl’s finishing school. (Of course, the girls are all nubile beauties who are okay with dorm-room topless scenes and quasi-lesbian fondling.) A moment later a carriage with Mircalla and her “aunt” (her real-life vampire mother?) arrives.

Lestrange connives to get a teaching job at the school and falls for the enchanting Mircalla. A mild, conservatively filmed love scene with them was added at the end of production to spice up the film. Unfortunately, a silly ballad, “Strange Love”, was laid on top of this scene. Johnson and Stensgaard howled with laughter when they saw the result. Critics hated that scene and panned the film.

This was not the big hit Hammer had expected, but did well enough to warrant another sequel. Or rather, another Karnstein-related story that has nothing to do with the previous films.

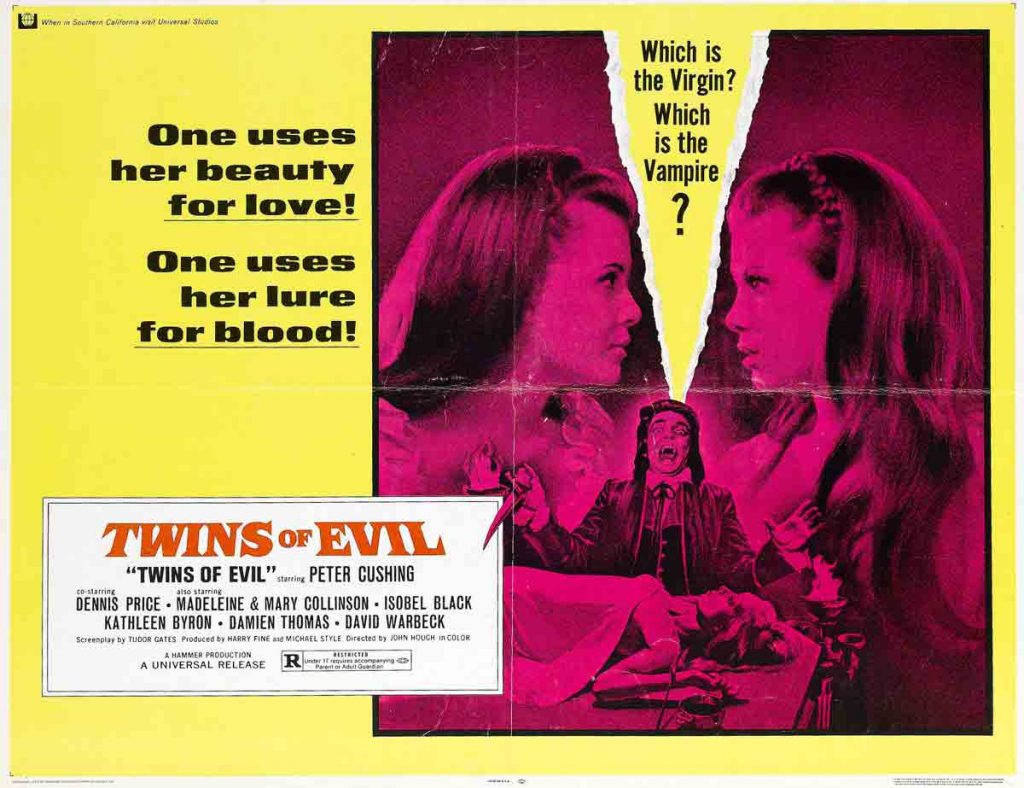

Twins of Evil (UK, 1971)

The return of one of the old Hammer managers meant this film (but not the advertising campaign) would be less exploitive, despite the presence of the notorious Collinson twins. Mary and Madeleine Collinson made nudie-mag history when they appeared in “Playboy” (October 1970) as the first identical twin Playmates. They enjoyed a few years of notoriety appearing in a handful of mildly risque B-movies.

Hammer used them to shamelessly promote their film with a series of provocative and misleading publicity stills. The twins posed nude, sometimes with other cast members, on a gothic-themed set. The photos look like scenes from the movie but have no relation to the actual film. In fact, this was the most conservative entry in the trilogy with the least amount of on-screen nudity.

The story is a prequel, set in the 1700s before Karnstein castle became a ruin. (This plot has no apparent connection to Le Fanu’s stories.) The twins play the fun-loving Gellhorn sisters sent to live with their cold, austere uncle, Gustav Weil (Peter Cushing). Weil is head of The Brotherhood, a band of fanatical, vigilante Puritans who spend their evenings going on witch hunts. Suspected witches are seized and immediately “purified by fire” by the pious brethren.

Meanwhile, the depraved, devilishly handsome Count Karnstein murders a girl during a satanic ritual. Blood seeps into the sepulcher of Mircalla (here her death is listed as 1547) and revives her spirit. She bites him on the neck, transforming him into an undead vampire. And that’s the last we see of her.

The rest of the story concerns evil twin Frieda who can’t tolerate her strict uncle and sees the sinister and exciting Count Karnstein as her salvation. She embraces the dark side and also becomes a vampire.

Needless to say, things don’t end well for these vampire lovers. There is the standard storming-the-castle finale with some action and a nifty beheading sequence. Like most Hammer films, not an artistic triumph, but a sturdy, competently made vampire yarn that stands on its own outside of the trilogy.

The Blood Spattered Bride (Spain, 1972)

Set in the present day, this strange and fascinating Spanish film is directed by Vicente Aranda. The story focuses on the sexual awakening and violent psychosexual fantasies of a young bride. A curious blend of misogyny and feminism woven into a surreal, quasi-supernatural story with casual links to “Carmilla” and vampirism.

Newlywed Susan (Maribel Martín) seems happy enough, yet she has a bizarre rape fantasy on her wedding night. This is the first in a series of increasingly disturbing hallucinations as fantasy and reality begin to merge. Her randy husband (Simón Andreu) shows a cruel side and starts treating her roughly which sends her over the edge in hysteria. They stay at his family estate where a portrait of Mircalla Karnstein, its face cut out, is stored in the basement.

Two centuries ago, she killed her husband on her wedding night. Mircalla appears in Susan’s dreams, biting her on the neck and giving her an antique dagger for killing her husband. There is a particularly gruesome scene of stabbing and dismemberment (hence the “blood spattered” title).

If that wasn’t strange enough, on a lonely stretch of beach, the husband finds a naked woman, still alive, buried in the sand. She is Carmilla (played by the hauntingly beautiful Alexandra Bastedo). She claims to have amnesia and stays with the newlyweds. And, she looks just like Mircalla from Susan’s dreams. Right away, a mysterious and powerful bond forms between the two women. Carmilla’s hatred of the husband, and all men, is instilled in Susan leading up to the inevitable confrontation and a fairly shocking ending.

A unique approach to “Carmilla” that goes its own way and tosses in a few neat twists. The story is more in the spirit of Polanski’s “Repulsion” than a traditional horror film. And most of the seemingly supernatural events and fantasies are grounded in reality. The director was obviously captivated by the feminist theme of lesbian revenge. His previous film, “The Exquisite Cadaver” (1969), was about a woman who torments the man who murdered her lesbian lover.

Television Productions

- Carmilla (1989) From Showtime’s Nightmare Classics cable TV series, this is set on a wealthy plantation in the 1860s South. A bland Ione Sky is Marie, a lonely Southern belle. A carriage accident brings Carmilla (a bewitching Meg Tilly) into their home as a guest. With her almond-shaped eyes and enigmatic Mona Lisa smile, Tilly is ideally cast as the coy vixen. Her Camilla has the power to disappear and summon hordes of killer bats. She also has a rat as a familiar. Not sure if any of these traits are from the original story. Tilly, and Ray Dotrice as the father, are good, but this one-hour production is a bit rushed. The so-so effects and artificial sounding “cable music” (which has too much harp), serves as a constant reminder that this is a TV movie.

- Carmilla (1980) This Polish made-for-TV movie has an attractive cast (confirming all suspicions that Polish women are hot), but a strangely quaint, archaic style (filmed in black and white) that feels more like something from 1960.

- Carmilla: Le coeur petrifié (1988) is a French TV movie that was not available for viewing.

Recent Independent Carmilla Films

- Carmilla (US, 1998) Directed by Jay Lind, starring Maria Pechukas. Obscure film from Evil Clown Productions and available from Draculina Cine. (Not available for review.)

- Carmilla aka The Vampire Carmilla (US, 1999) From Scorpio Pictures, directed, written, and starring Denise Templeton. This has been described as an abysmal vampire soap opera that owes more to “Dark Shadows” than J. Sheridan La Fanu. (Not available for review.)

- Carmilla, the Lesbian Vampire (US, 2004) also released as “Vampires vs. Zombies”. Directed by Vince D’Amato and starring Bonny Giroux, C.S. Munro, and Maritama Carlson. This film, which I have not seen, has been panned as one of the worst movies ever made.

- Carmilla’s Kiss (US, 2007) A dark horror-comedy about an ambitious director staging a play based on “Carmilla”. One night, his eccentric cast meets him at a remote and forbidding house to rehearse in the cellar that inspired the play’s unfinished set. The cellar, a rumored ancient place of worship, even has its own altar. As night passes, inhibitions fade, passions burn, and tempers flare. Director: Michael McGovern (not available for review).

- Carmilla (Argentina, 2010) This Spanish-language production, described as an action movie, was not available for review. Written and directed by Ernesto Aguilar.

Closing the Lid

Besides comparing story adaptations and film techniques, this little study also reveals some of the differences in approach and style by the many nationalities involved.

The Danish-German “Vampyr” stems from a love of spooky folklore and moody, visual novelties and innovations – at a time when Hollywood was taking few risks.

The elegant, artistic style of the French is represented, as is the Gothic romanticism and sensuality of the Italians.

The British films are more straightforward, restrained, and skip over the surreal possibilities of the supernatural. From Spain comes a typical Catholic-guilt sex-and-death psycho-drama that ends in bloody tragedy for virtually the entire cast.

The more recent films from America involve a mix of all of the above plus dark comedy and some trendy genre-blending.

JIM IVERS is an artist, occasional writer and copy editor for publishers that have the nasty habit of going out of business. He lives in the U.S. and currently writes about various film genres for “The Kobb Log”, a horror-SF-fantasy ‘zine.