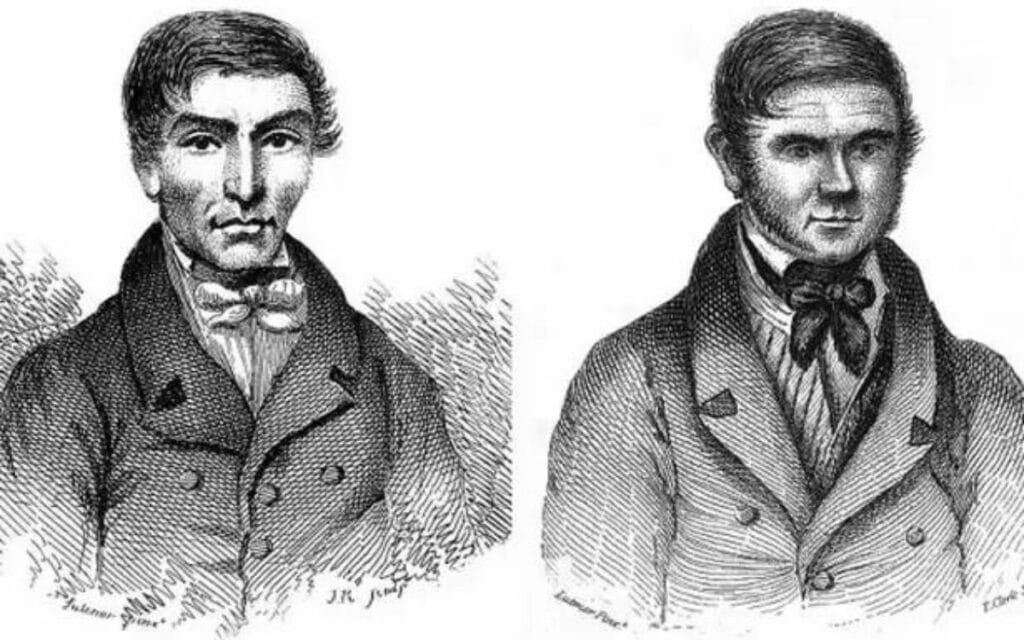

JOHN AMBROSE MARTIN takes us back to ‘Auld Reekie’ Edinburgh at the beginning of the 19th century for 10 things you didn’t know about the infamous Bodysnatchers, Burke and Hare.

At the start of the 1800s, there had been many advancements in the sciences and medicine was no exception. Edinburgh was a leading European centre of anatomical study in the early 1800s, But in order to study human anatomy you need bodies or cadavers to dissect and study!

Bodysnatchers were actually called Resurrection Men!

Such was the demand for cadavers, it led to a shortfall in legal supply. Scottish law required that corpses used for medical research should only come from those who had died in prison, suicide victims, or from foundlings and orphans. The shortage of corpses led to an increase in body snatching by what were known as “resurrection men”. Measures to ensure graves were left undisturbed; such as the use of mortsafes only exacerbated the shortage.

Burke and Hare were Irish and both called William!

William Burke was born in 1792 in Urney, County Tyrone, Ireland, one of two sons to middle-class parents. Burke, along with his brother, Constantine, had a comfortable upbringing, and both joined the British Army as teenagers. Burke married a woman from County Mayo, where they later settled. The marriage was short-lived and after an argument with his father-in-law over land ownership, Burke deserted his wife and family. He moved to Scotland and became a labourer, working on the Union Canal. He settled in the small village of Maddiston near Falkirk, and set up home with Helen McDougal, whom he affectionately nicknamed Nelly; she became his second wife.

William Hare has more mystery surrounding him, only knowing he was born in one of the six counties of Northern Ireland. Hare ended up in Scotland, working on the Union Canal for seven years before moving to Tanner’s Close in Edinburgh to work as a coal man’s assistant.

Burke and Hare met in 1827 when both men went to Penicuik in Midlothian to work on the harvest. The men became friends; when Burke returned to Edinburgh, he moved into Hare’s Tanner’s Close lodging house, where the two soon acquired a reputation for hard drinking and ‘boisterous behaviour’.

Seven Pounds, Ten Shillings – The Price of Burke and Hare’s First Body Sale!

29 November 1827 is the date it all began. Donald, a lodger in Hare’s house, died of dropsy shortly before receiving a quarterly army pension while owing £4 of back rent. After Hare bemoaned his financial loss to Burke, the pair decided to sell Donald’s body to one of the local anatomists.

A carpenter provided a coffin for a burial which was to be paid for by the local parish. After he left, the pair opened the coffin, removed the body, which they hid under the bed and filled the coffin with bark before resealing it. After dark, on the day the coffin was removed for burial, they took the corpse to Edinburgh University, where they looked for a purchaser.

The men received £7 10s for the cadaver from Dr Robert Knox of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Hare received £4 5s while Burke took the balance of £3 5s. Hare’s larger share was to cover his loss from Donald’s unpaid rent. According to Burke’s official confession, as he and Hare left the university, one of Knox’s assistants told them that the anatomists “would be glad to see them again when they had another to dispose of”.

This one event would lead to one of the infamous killing sprees in Edinburgh’s history.

Burking was a Murder Technique!

There is no agreement as to the order in which the murders took place as confessions, interviews and statements seemed to change each time. But historian Lisa Rosner considers a miller named Joseph the most likely be the first victim and probably smothered by pillow. Later victims were suffocated by Burke with a hand over the nose and mouth while Hare pinned them down. This unique form of murder was to preserve the body from as little harm and damage as possible. Later a new word was coined from the murders called ‘Burking,’ meaning ‘to smother a victim or to commit an anatomy murder’.

Later a rhyme began circulating around the streets of Edinburgh:

‘Up the close and doon the stair,

But and ben’ wi’ Burke and Hare.

Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief,

Knox the boy that buys the beef.’

The Final Victim was Irish and this is when the Luck of the Irish ran out!

The final victim, killed on Halloween night 1828, was Margaret Docherty, a middle-aged Irish woman. Burke lured her into his lodging house by claiming that his mother was also a Docherty from the same area of Ireland, and the pair began drinking. At one point Burke left Docherty in the company of Burke’s second wife Helen, while he went out, claiming to be buying more whisky, but actually to get Hare.

Two other lodgers — Ann and James Gray — were an inconvenience to the men, so they paid them to stay at Hare’s lodging for the night, claiming Docherty was a relative. The drinking continued into the evening, by which time Margaret had joined in. Around 9pm the Grays returned briefly to collect some clothing for their children, and saw Burke, Hare, their wives and Docherty all drunk, singing and dancing. Once the intruders had left, Burke and Hare murdered Docherty, placing her body in a pile of straw at the end of the bed.

The next day the Grays returned, and Ann became suspicious when Burke would not let her approach a bed where she had left her stockings. When they were left alone in the house in the early evening, the Grays searched the straw and found Docherty’s body, showing blood and saliva on the face. On their way to alert the police, they ran into Helen, who tried to bribe them with an offer of £10 a week but they refused.

While the Grays reported the murder to the police, Burke and Hare removed the body and took it to Knox’s surgery. The police search located Docherty’s bloodstained clothing hidden under the bed. When questioned, Burke and his wife claimed that Docherty had left the house, but the police were not convinced and the pair were brought in for questioning. Early the following morning the police went to Knox’s dissecting rooms where they found Docherty’s body. Hare and his wife were arrested that day; all denied any knowledge of the events.

William Hare actually turned on his Partner in Crime!

On 1 December, Hare was offered immunity from prosecution if he turned king’s evidence and provided the full details of the murder of Docherty and any others. Because the law forbade the testifying of one spouse against another, Hare’s wife was also exempt from prosecution. Hare made a full confession of all the deaths and Sir William Rae, the Lord Advocate, decided sufficient evidence existed to secure a prosecution. On 4 December formal charges were laid against Burke and his wife for the murders of Mary Paterson, James Wilson and Mrs. Docherty.

William Hare took the stand to give evidence. Under cross-examination about the murder of Docherty, Hare claimed Burke had been the sole murderer and McDougal had twice been involved by bringing Docherty back to the house after she had run out; Hare stated that he had assisted Burke in the delivery of the body to Knox.

A Christmas Eve Trial and a Christmas Day Verdict!

After a long investigation the trial began at 10am on Christmas Eve 1828 before the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh’s Parliament House. This was a spectacle and people from all around filled the courthouse inside and out. Three hundred constables were on duty to prevent disturbances, while infantry and cavalry were on standby as a further precaution.

The jury retired to consider its verdict at 8:30am on Christmas Day and returned 50 minutes later. It delivered a guilty verdict against Burke for the murder of Docherty, while his wife was found not guilty due to lack of evidence. As the death sentence was passed, Burke was told: “Your body should be publicly dissected and anatomised. And I trust, that if it is ever customary to preserve skeletons, yours will be preserved, in order that posterity may keep in remembrance your atrocious crimes.”

Burkes’s Execution was a Pay Per View Event!

Burke was hanged on the morning of 28 January 1829 in front of a crowd possibly as large as 25,000. Views from windows in the tenements overlooking the scaffold were hired at prices ranging from 5–20 Shillings.

Burke became a medical cadaver himself!

On 1 February, Burke’s corpse was publicly dissected by Professor Monro in the anatomy theatre of the university’s Old College.

Police had to be called when large numbers of students gathered demanding access to the lecture for which a limited number of tickets had been issued. A minor riot ensued; calm was restored only after one of the university professors negotiated with the crowd that they would be allowed to pass through the theatre in batches of fifty, after the dissection. During the procedure, which lasted for two hours, Monro dipped his quill pen into Burke’s blood and wrote,

“This is written with the blood of WM Burke, who was hanged at Edinburgh. This blood was taken from his head”.

William Hare survived and vanished but you can still visit William Burke in person!

Hare was released on 5 February 1829—his extended stay in custody had been undertaken for his own protection. He was assisted in leaving Edinburgh in disguise by the mail coach to Dumfries and was told to head for the English Border. There were no subsequent reliable sightings of him and his eventual fate is unknown.

Dr Robert Knox refused to make any public statements about his dealings with Burke and Hare and remained impervious to prosecution.

Burke’s skeleton was given to the Anatomical Museum of the Edinburgh Medical School where it remains. His death mask and a pocketbook said to be bound with his tanned skin can be seen at Surgeons’ Hall Museum.

JOHN AMBROSE MARTIN has been a paranormal investigator and researcher since 2004. He has a passion for history, folklore and all things supernatural. Currently a member of Púca Paranormal, John has investigated the most haunted locations in Ireland and Scotland. John hopes to bring you stories of his paranormal adventures as well as some interesting characters and tales he comes across in his research.