Guest writer VIOLET FENN explores the history of the British fascination with death

For as long as humans have walked the earth there have been burial traditions worldwide and Britain was no exception.

In the Paleolithic era we were still hunter-gatherers and lived nomadic lives; even so, there is some evidence to show that cave burials took place. However undeveloped our social strata, respect for the dead was evidently already established.

By Neolithic times man was beginning to live in more settled environments – customs surrounding death and burials became more structured now that descendants would still be around to tend the remains.

This was the era of the long barrows such as West Kennet, near Avebury – chambered tombs that held many bodies and which were covered in earth when full. These have a visible impact on the British landscape to this day.

The introduction of Christian traditions by the Romans led to burial customs that are more akin to those we use today. Early version of cemeteries were developed on the outskirts of settlements – Roman law forbidding the burial of bodies within settlements themselves.

It was traditional for Christians to be buried with their bodies aligned East-West (feet pointing East). Interestingly, priests were buried in the opposite direction, in order that they faced their parishioners in death as they did in life.

There was a return to pagan ritual in Great Britain after the fall of the Roman Empire – the Anglo Saxons ushered in the beginnings of what we today would call the Early Medieval period, and which for some time was known as the Dark Ages (this term has now fallen out of use – ‘dark’ implied lack of Christian belief).

Pagan beliefs led the Saxons to inter bodies with ‘grave goods’ such as food, jewellery and weapons, in order to both appease the gods and also help the deceased’s passage into the afterlife. This period also saw the development of cremation – remains have been found of large Saxon cemeteries containing ashes buried in urns, alongside the more usual interments. Although a rarity in Britain, the Saxons also practiced ship burials, the most famous of which took place at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk.

Britain returned to Christianity with the ascendance of Richard I in the twelfth century and Catholicism held sway until Henry VIII introduced Protestantism in the mid-1500’s.

The ornate high point of modern attitudes towards death arrived with the Victorians and their love of gothic imagery.

One of my own favourite oddities began to appear at this time – the caged graves known as mortsafes. Their strange appearance has given rise to endless myths over the years, the most popular being that the cages were erected to keep the dead from rising and leaving their eternal resting place.

The rather more prosaic truth is that as anatomical study became increasingly popular with the medical profession, some families felt it worthwhile ensuring that their loved ones weren’t dug up to be the subject of medical students’ classes.

Flamboyantly decorated tombs and graves were common during this era. The rapid expansion of the British population during Victoria’s reign was another reason for the increase in the number of cemeteries (a cemetery is a graveyard that is not attached to a church) – there was simply no longer enough room to bury everyone within urban boundaries.

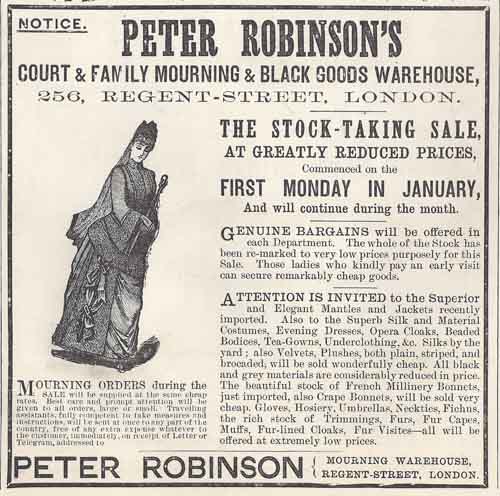

Mourning dress really came into its own at this time, with carefully prescribed rules and codes regarding what could be worn, and when. A widow was expected to wear mourning for two years, although she was permitted to change to ‘half mourning’ after the first 12 months which meant that she could wear shades of grey and lavender.

A popular custom was to use locks of the deceased’s hair to create ‘memento mori’ jewellery – usually pendants and brooches containing intricately curled and woven strands, but occasionally bracelets made of hair that was boiled (to soften it) and then plaited.

The custom of mourning dress began to fade after the death of Queen Victoria, although for much of the early 20th century it was still considered ‘proper’ to wear dark clothing for a period of time after the death of a loved one.

An increasingly secular society (along with dwindling space in graveyards) has led to an increase in the number of cremations over the last century.

Cremation is now by far the most popular way to dispose of a human body in the UK, rising from 34% in 1960 to more than 70% in 2008. At first considered to be an environmentally viable option as it doesn’t take up land space, cremation has now become a genuine source of concern because of the airborne pollution that can be created by crematoria gases and the mercury that is released when filled teeth are burnt.

Death and the associated disposal of the body is now sanitized and often based more on admin than religion. Whereas a few decades ago we would have kept our dead at home before going to church, we are now much more likely to meet the coffin at the crematorium and head to the alcohol-fuelled wake straight afterwards. ‘No black’ is now a common request, and we are often required to sing along to football anthems or pop songs during the service (and yes, ‘My Way’ by Frank Sinatra is still the most popular funeral song).

But even in today’s more secular society, we still often wish to have a physical memory of our dear departed, and there are several ways of doing so that don’t involve keeping them in an urn on the mantelpiece. Celestis will shoot your loved one’s ashes into space, and Ashes Into Glass will create a beautiful solitaire ring out of ashes mixed into glass.

Now that would look good against a black taffeta mourning gown…

You can read more of Violet Fenn’s work on her blog The Skull Illusion, which focuses on Post Mortem Photography and other usual aspects of death. Her previous article for The Spooky Isles can be seen here.

Excellent article. One thing to also bear in mind is that the 1832 Anatomy Act legitimately gave medical dissectionists access to cadavers in the form of people who had died in workhouses and others who had been executed. So after that time there would have been little reason for bodies to be dug out of graves or tombs broken into.

Hi Mel 🙂 Yes, I know about the 1832 Act. The fact that this came into existence is certainly a big factor in there being only a few mortsafes in existence – there wasn’t a great deal of them around to start with, as the trade in illegal cadavers didn’t last for very long.