JIM IVERS ponders the many film ‘sequels’ to Dracula that involve the off-spring and other relations of the King of Vampires

This study takes a look at the films featuring Count Dracula’s extended family. This is both a critical assessment of the individual titles as well as an attempt, wherever possible, to provide historical context and anecdotal background information on the making of these films.

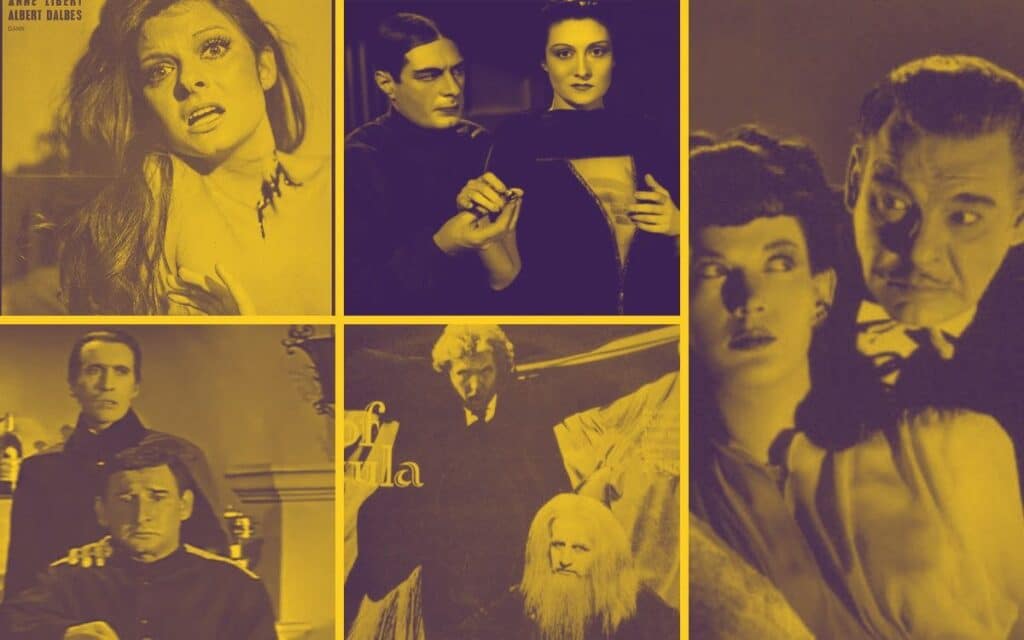

Dracula’s Daughter (Universal, 1936)

The screenplay was (very) loosely adapted from Bram Stoker’s short story “Dracula’s Guest” (1914), which was a chapter cut from his 1897 novel “Dracula”. (This concerns a traveler who encounters a strange woman in a graveyard who turns out to be a vampire.) There are also traces of Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla”. (See “The Carmilla Vampire Films” article also on this site.) This movie marks the end of the first horror film cycle from Universal Pictures. And, it’s an example of how films were negatively affected by overly strict censorship during that time.

Years before the term “horror movie” even existed (they were called “mystery plays” at first), Universal created the archetypes of horror cinema with “Dracula”, “Frankenstein” (both 1931), “The Mummy” (1932), et al. Sequels were not yet part of the industry mindset. The monster dies in the finale, and that’s it; on to the next. The one big exception was RKO’s “Son of Kong” (1933), quickly thrown together to cash in on the blockbuster success of “King Kong”. (A sequel with about as much artistic integrity as Irwin Allen’s “Beyond the Poseidon Adventure”.)

In 1934 the three-year-old “Frankenstein” was still making a profit in second-run theaters. And over at MGM, the Tarzan sequel, “Tarzan and his Mate”, was a smash. This encouraged Universal to resurrect Frankenstein’s monster and make the excellent “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935). A great critical and box-office success, the film legitimized sequels and led to the making of “Dracula’s Daughter”.

However, MGM announced they were developing a competing Dracula script. In their story, Dracula’s three brides were enslaved and tormented by his cruel, whip-cracking daughter. MGM was emulating DeMille who was making a fortune exploiting sex and sadism in epics like “Sign of the Cross”. A nervous Universal, despite being nearly bankrupt, was forced to purchase the option from MGM. Some historians claim MGM had no real intention making the film and concocted the rival script so Universal would have to buy them out. (Cut-throat competition for the lucrative horror market led to MGM snapping up Lugosi and “Dracula” director Tod Browning for “Mark of the Vampire” released in April 1935.)

Universal turned to the brilliant but eccentric James Whale to direct “Dracula’s Daughter”. Earlier, Whale tried to subvert “Bride of Frankenstein” by tossing in all sorts of off-the-wall ideas and campy comic relief bits as he wanted to leave the horror genre and return to sophisticated comedies and dramas. The script he submitted for the new movie was so outrageous he was taken off the project. Lambert Hillyer, fresh from “The Invisible Ray” with Karloff, directed.

The screenplay then went through several complete rewrites. The original story, along with the three brides, were discarded. Universal was constantly harassed by the Production Code Administration (PCA) over what it considered “an objectionable mixture of sex and horror”. The story had to be completely re-plotted to comply with censorship requirements. Rewrites continued almost all through the chaotic production period.

The exotic Zita Johann (from “The Mummy“) was the first choice to play Dracula’s daughter, but the role eventually went to the more imposing Gloria Holden. Edward Van Sloan reprised his role as Prof. Van Helsing — the only actor from “Dracula” to return. Initially Universal wanted Lugosi, Jane Wyatt, Karloff, and Colin Clive, but nothing came of these casting choices. And a number of ghoulish and sexually-charged flashback scenes featuring Lugosi as Dracula had to be jettisoned due to censorship pressure from the powerful Breen Office.

Unfortunately the final script cut Dracula out of the story entirely. Universal literally burned its bridges behind them by showing the cremation of Dracula’s body in the opener. A huge mistake considering how much better (and more successful) the film would have been with Lugosi as the immortal Count. The studio missed a golden opportunity to launch a series of highly profitable Dracula films. But at the time, even “Bride of Frankenstein”, despite being a big hit, was seen as a one-shot fluke.

The story begins in Carfax Abbey immediately after Van Helsing kills Dracula in the first film. Police arrest him for murder and put Dracula’s body in a holding cell. The mysterious Hungarian countess Marya Zaleska (Holden) appears that night, hypnotizes the guard with her ruby ring and steals her father’s remains. By burning him in an occult ritual in a remote forest she believes she can be released from her own vampirism and return to normal life. This does not work (nor does it conform with established vampire lore). The spirit of Dracula seems to control her even from beyond the grave.

Back in London, she seeks the aid of noted psychiatrist Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger in the Colin Clive role), believing his radical hypnotherapy methods can free her from what she vaguely describes as “an evil influence”. Alas, this does not work either. Once a vampire, always a vampire.

The most noteworthy scene in the film, which owes its influence to “Carmilla”, has obvious (and deliberate) lesbian overtones that were pretty daring for its time. Marya has a sculpture studio and sends out her manservant Sandor to pick up models (presumably prostitutes and transients) off the street. He finds a beautiful girl about to throw herself off a bridge and brings her to the studio. Marya has her expose her shoulders (the original script had her posing nude) then slowly moves in for the kill, flashing her hypnotic ring. Although the camera demurely pans up to a tribal mask on the wall during the actual neck biting and scream, the scene has a palpable sensuality that must have raised a few eyebrows. This is the only racy bit that got past the PCA censors. However, a few conservative states trimmed off the ending of this scene.

Irving Pichel is excellent as Sandor (the part written for Karloff). Tall and imposing, he has a quiet menace and a deep sinister voice that is perfect for the role. He’s the opposite of Dracula’s flunky Renfield, an obsequious, bug-eyed weasel. And Gloria Holden is a most convincing vampire with her darkly aristocratic features and large, haunting eyes.

Though well-directed and acted, there are far too many talky scenes and only occasional bits of Gothic atmosphere to sustain the mood. The finale at Dracula’s castle hints at what this could have been. It’s jolting to see the main hall with its sweeping staircase looking exactly as it had in the original film. For a moment the old feeling of excitement and magic seems to return before the all-too-abrupt ending. There is no doubt that the constant meddling of the PCA is to blame for gutting the original story resulting in a watered down film

There are some technical issues that are hard to ignore. Dracula, we are told, is around 500 years old. His daughter is around 130. Standing over Marya’s dead body, Van Helsing delivers a wonderfully chilling closing line: “She was beautiful when she died — a hundred years ago”. It seems impossible for the Count, a living corpse, to sire a biological offspring. She would have to be a past victim or orphan that he adopted and eventually turned into a vampire. But, as said before, horror films do not invite speculation or hold up under scrutiny. One has to suspend disbelief and accept whatever crazy dream-logic, psycho-babble and pseudo-science the writers have concocted to advance the story.

The idea of using science to defeat supernatural forces (a rationalist approach common in U.S. films) will return in “House of Dracula” (1945). Both the Count and the Wolf Man seek a medical cure for their afflictions. In the ’60s and ’70s Jean Rollin revived this concept in several erotic horror films about reluctant vampires.

This was the last Universal film under the supervision of Carl Laemmle Jr. The company had always been a family-run business with scores of relatives on the payroll. Days after production wrapped, Universal defaulted on a huge loan and Standard Capital Corp. seized control of the studio and kicked the Laemmle family out. Horror was also out that year due to increasing pressure from the PCA. Thus, horror films went on a self-imposed two-year hiatus. (See “The Horror Hiatus of 1936-1938” on this website for a detailed account of this period.)

Son of Dracula (Universal, 1943)

Lon Chaney (the “Jr” was dropped from his name) plays suave Count Alucard (get it?) who journeys from Budapest to a Southern plantation in the U.S. to marry an occult-obsessed heiress and continue his life of nocturnal crime. First, the title is a misnomer. Late in the story, Alucard is revealed to be Count Dracula himself. By rights, this should have been called something like “The Return of Dracula”. However, Lugosi embodies that role like no other actor. It seems “Son” was added to throw off audience expectations so they would accept Chaney as the titular vampire. By the time of the big reveal, one is so deeply invested in the story that it doesn’t matter as much.

Universal may have also wanted to evoke “Son of Frankenstein” (1939), the box office hit that began a second cycle of horror films for the studio — and the industry in general, ending the horror hiatus period. In the ’40s Universal also pioneered the horror series concept (along with the “all star” monster mash-up). With three highly profitable film series based on Frankenstein, the Mummy, and the Wolf Man, it is likely they were also considering a Dracula franchise as well.

But why Lon Chaney? Critics seem to agree that Chaney did a fairly credible job despite being miscast in the role. His appearance, which includes graying hair, a pencil mustache, and pasty makeup, makes him look more like a bulky Clark Gable than The Prince of Darkness. Chaney excelled at playing nice guys trapped by horrific circumstances beyond their control. He is extremely sympathetic and likable as an average, working-class Joe in “Man Made Monster” (1941) and the haunted Larry Talbot in the Wolf Man films. But he lacks menace as a villain and is ill-suited to play an elegant Hungarian vampire. It’s been said that Lugosi is an aristocrat of evil while Karloff, although a better actor, is a proletarian of it. The earthy, heavy-footed Chaney suffers from the same lack of individual flair.

Chaney was cast because he was Universal’s biggest box office star at the time. Karloff was away doing “Arsenic and Old Lace” on Broadway. And the neglected Lugosi was shoved into the background as Universal’s most woefully under-utilized resource. He was given small supporting roles (a butler in 1942’s “Night Monster”) and was terribly miscast as the Monster in “Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man” (1943).

The studio’s consistently shabby treatment of Lugosi is legendary, but they really dropped the ball with this film. Poor Lugosi, who had a tiny bit part in “The Wolf Man”, must have been hurt at being passed over once more. But he got his revenge as we shall see later.

Despite the casting, this is a surprisingly well-made film that’s more entertaining (and far less talky) than “Dracula’s Daughter”. Following the example of the low-cost Mummy sequels, the story is relocated to the frame-and-shingle world of rural America. The fog-swept woods and swamps in this Deep South setting provide a properly eerie atmosphere. Most memorable is Dracula’s coffin emerging like a ghostly U-boat from the misty waters of a midnight pond. Wisps of smoke from the coffin solidify into the Count; he then glides above the water. There are several terrific smoke transformation effects and the first bat-to-human transformations done for the screen. The direction, fluid camerawork, and moody lighting (contrasting dramatic slashes of light and shadow) is superb, giving this the rich look of an “A” picture on a “B” budget. A text book example of how to use film-noir lighting techniques to create a dense atmosphere of foreboding. Director Robert Siodmak went on to make many highly-regarded noir crime dramas such as “Phantom Lady” (1944), “The Spiral Staircase” (1945), “The Killers” (1946), and “Criss Cross” (1949).

The original story is by his brother Curt Siodmak who also wrote “The Wolf Man” (1941), “Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man” (1943), “The Invisible Man Returns” (1940), et al. This tale ignores the first two films and describes Dracula as a legend from the Middle Ages who was destroyed in the 19th Century. The story has some unexpected twists and turns and a neat ending.

This has a typical Van Helsing clone in the form of Professor Lazlo, a bespectacled, pipe-smoking Hungarian. He provides the obligatory bridge between the supernatural and everyday reality with a mix of science and folklore. This is for the benefit of the no-nonsense doctor investigating Alucard as well as a mostly rationalist American audience.

But the most interesting character is Kay (Louise Allbritton), a dark-haired beauty with Bettie Page bangs. Obsessed by dark forces, she is described as having a “morbid” personality. She befriends Madame Zimba, a voodoo fortune teller, and becomes infatuated with Dracula’s power and wants eternal life as a vampire.

The unconventional head-strong Kay has elements of Scarlett O’Hara. A rather amusing speculation among some writers is that the script is actually a covert take-off on “Gone With the Wind”. The old world Southern plantation setting, the Tara-like mansion, and the troublesome intruder Chaney as a Rhett Butler-lookalike all seem to support this theory.

Released in November 1943, the film did well in theaters and got good notices overall. Two months later Columbia Pictures made an audacious move to steal Universal’s fire by putting out the similar “Return of the Vampire”. This boasted Bela Lugosi’s triumphant return as the definitive vampire we all know as … Armand Tesla? For copyright reasons they couldn’t call him Dracula, but the implication was clear. Tesla, like Alucard, was just another alias for the immortal Count. Having Lugosi, the real article, in a de facto Dracula role must have shocked Universal and cut into “Son” at the box office. If that wasn’t galling enough, Lugosi/Tesla has a pathetic, slavish wolf man serving him. Not surprisingly, Lugosi was shunned from Universal (John Carradine played Dracula in the next two films). In 1948 Universal reluctantly hired Lugosi one last time to play Dracula in “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein”.

Uncle Was a Vampire aka “Tempi duri per i vampiri” (Italy, 1959)

Just one year after his first Dracula film (Hammer’s “The Horror of Dracula”, a massive hit), Christopher Lee spoofs his image in this tepid Italian attempt at horror-comedy. The diminutive Renato Rascel has the lead role as a hapless doofus named Osvaldo Lambertenghi. Rascel is like a poor man’s Lou Costello/Jerry Lewis type, only without the personality, energy, or comic timing. He sells his family’s castle overlooking the scenic Mediterranean and stays on as a bellboy when it’s converted into a hotel. (The sunny setting provides an excuse to show off some bikini-clad Italian babes in a few scenes.)

Then his uncle, Baron Roderico da Frankurten (Lee), arrives from Germany – inside a shipping crate. The Baron is a 400-year-old vampire who looks and acts just like Dracula. Lee wears a dramatic black and red cape and is covered in pasty gray makeup to give him a dead pallor. The makeup looks terrible. An echo effect is also used on his voice (dubbed in English by another actor) to make it sound more otherworldly. The Baron is annoyed to find the ancestral castle full of tourists and his crypt turned into a bar. After some unfunny conflict, he bites Osvaldo, temporarily turning him into a sort of vampire with gray skin and an identical cape. He looks like a mini-me version of Lee. Osvaldo bites a few girls on the neck who then fall in love with him. Dull, insipid complications ensue.

Lee plays it straight, which is mildly amusing at times, while Rascel fails to do much of anything. He’s supposed to be a bumbling comedic character but does nothing funny — no slapstick, sight gags, or verbal humor. He’s just a dimwitted, faintly inept guy who walks through scene after scene. Unfortunately, Lee, along with some nice color photography, a beautiful setting, and some pretty girls (including Sylvia Koscina), are wasted in this inconsequential piece of Italian fluff.

Dracula’s Daughter aka “La fille de Dracula” (France, 1972)

Written and directed by the absurdly prolific Jess Franco, this stars the stunning Britt Nichols as Luisa Karlstein. It’s no coincidence that her character name is similar to Karnstein from the “Carmilla” novella. However, this lesbian vampire frolic of fancy has no direct link to Sheridan Le Fanu’s story.

Luisa’s dying grandmother reveals the family curse: they’re all vampires. She moves into the estate with some relatives and starts doing lesbian stuff with her cousin Karine (Anne Libert). Meanwhile, a masked killer from a giallo movie is running around. Luisa finds a coffin in the basement. Inside is Count Karlstein (aka Dracula) played by Franco regular Howard Vernon. But the bug-eyed Count never gets out of his coffin. He only sits up and hisses menacingly now and then. This frightens Luisa so she has more lesbian sex with Karine while a guy plays classical piano in the next room. This manages to kill about 8 minutes of screen time without advancing the plot one bit. A very curious scene as we cut back and forth from the two girls awkwardly caressing each other to the piano player. A hand-held camera is used as we roam around the piano, examining it from every angle. The fact that the operator’s shadow appears on camera apparently did not bother Franco.

This is one of Franco’s many “free range” films that roam about without much logic or purpose, much like a barnyard chicken. There is some elegant, almost dream-like imagery, some nicely filmed scenery and old buildings in Portugal and Spain, gorgeous women who are okay with nude scenes, the usual simulated lesbian groping, lingering close-ups of body parts, a little vampire neck-biting, and not much else. The sketchy, barely-there plot is very confused and arbitrary. Just random ideas and afterthoughts loosely thrown together and released as a film. This type of undisciplined noodling is characteristic of much of his work from the ’70s and later. To save money, Franco usually shot two or three films simultaneously, often without the benefit of a script, and with little attention paid to continuity or narrative logic. Much like Jean Rollin, Franco was a dreamer who put his dreams on film, without apology or explanation.

Son of Dracula (UK, 1974)

Released by Apple, the notoriously mismanaged company created by The Beatles (read “The Longest Cocktail Party” by Richard DiLello for an entertaining insider’s account). Harry Nilsson stars as Dracula’s son, Count Downe; Ringo Starr is Merlin the Magician (with a white beard, a corny cape and conical hat similar to what he wore in “Magical Mystery Tour”). This was directed, apparently over the phone, by Hammer/Amicus veteran Freddie Francis. The cast also includes Hammer regular Dennis Price as Van Helsing and Suzanna Leigh as Amber (she was in “The Lost Continent” and “Lust for a Vampire”).

Filmed in 1972 but not released until 1974 because, as Ringo put it, “No one would take it.” It’s easy to imagine Ringo coming up with this idea during a long night with drinking buddy Nilsson. Ringo: “I’ve got it — we’ll do a spoof of a Hammer vampire film. You’ll play a reluctant vampire who’s also a musician. He just wants to play music and experience human love. You can perform a bunch of songs and we’ll produce a killer soundtrack album.”

Set in the present day, the scruffy, bearded Nilsson walks through the role of Count Downe. He may be a great musician, but Nilsson has the dramatic acting chops of a young Bob Denver. Throughout the film he seems distracted (or hung-over) and exudes the onscreen charisma of a boiled ham. The always likable Ringo isn’t much better, but has considerably less screen time. The story, such as it is, concerns the upcoming coronation of Downe as King of the Netherworld at a monster’s convention held in the basement dungeon of a horror museum. But Downe (who doesn’t behave like a vampire or drink blood) wants to revert back to being a mortal human again thanks to a process created by Dr. Van Helsing. Along the way he falls in love with Amber (Suzanna Leigh) and performs four songs with his band, The Count Downes.

The movie is worse than you could possibly imagine and fully deserves the obscurity in which it has languished. Every aspect of this cinematic train-wreck (story, acting, direction, editing, sets, effects, etc.) is sloppy and amateurish in the extreme. This is one of those lazy attempts at parody where the concept itself is supposed to carry the film. There is certainly nothing even faintly amusing or satirical in the script penned by actress Jennifer Jayne. (She wrote just one other script, the disappointing “Tales That Witness Madness”, also directed by Freddie Francis.)

This movie is so bad it was barely released to theaters and is not available on DVD. A few bootleg VHS videos surfaced sometime in the ’80s. (I managed to find it posted on YouTube.) The only thing that’s worthwhile are the musical numbers in which we glimpse Keith Moon, John Bonham, Peter Frampton, and an uncredited Leon Russell, backing up Nilsson as The Count Downes. All the songs but one, “Daybreak”, are from two previous Nilsson albums. The soundtrack also includes his definitive cover version of Badfinger’s “Without You” which was a massive hit.

Dracula and Son (France, 1976)

Christopher Lee once again makes fun of his Dracula image. This is really a story of two films. The original French movie is a subtle, mildly witty light comedy (but still not a very good film). In 1979 a radically different English dubbed version was created for release in the U.S.

Several scenes were cut and much new dialog, plus narration (and voice-overs revealing what the characters are thinking), was added. The totally reworked, joke-filled dialog makes this feel like Woody Allen’s “What’s Up Tiger Lily?” combined with Mel Brooks’ “Young Frankenstein”. Unfortunately, “Dracula and Son” isn’t half as funny as either of those two films. Nearly all the new material falls flat. And it doesn’t help that another voice actor dubbed Lee’s dialog.

Lee did his last Dracula film for Hammer (“The Satanic Rites of Dracula”) in 1973. He then turned down “The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires” (1974), claiming the script was “rubbish”. So, it must have appealed to him to do a genre spoof at this point in his career. The story begins in 1784 with Dracula raising a young son, Victor, in his castle. We rapidly cover the next two centuries as historical events transpire and Victor gradually matures to adulthood.

Most of the story takes place in present day Paris with Dracula trying to adjust to the modern world while his estranged son longs for a normal life as a mortal. At one point Dracula gets a job acting in a vampire film because “he looks just like Christopher Lee”. Not the most subtle humor, but there are a few amusing bits such as Dracula unknowingly biting the neck of an inflatable sex doll. This film, like Ringo’s “Son of Dracula” has remained very obscure and hard to find, and there’s a good reason for it.

Nocturna: Granddaughter of Dracula (1979)

Nai Bonet is Nocturna; John Carradine plays Count Dracula for the fourth and final time; and Yvonne De Carlo is Jugulia Vein (a vampire similar to her Lily Munster role). Unfunny German comic Brother Theodore plays “Theodore”, Dracula’s half-mad werewolf assistant. However, we never see him turn into a werewolf. He’s just an annoying crazy guy who talks to himself and rants a lot. The soundtrack features numerous disco songs by Gloria Gaynor, Vicki Sue Robinson, and performances by The Moment of Truth, et al.

Incredibly, this attempt at a horror-based romantic comedy (with music) drags Dracula into the New York disco scene of the 1970s. Deal with it. After a few bit parts in films and TV, Vietnamese belly-dancer and singer Nai Bonet decided to launch a serious acting career with this star vehicle. Filmed in 1978, this bizarre combination of vampire spoof and trendy disco nonsense is a total “jumping the shark” misfire.

The story, which has much in common with the previous two films, is what I call a matchbook plot. That is, a story so simple you could write it on a matchbook cover. Nocturna is a reluctant vampire who falls in love with a mortal who plays in a disco band (The Moment of Truth).

She runs away with him to New York and stays in a crypt-like room beneath the Brooklyn bridge with Jugulia. Dracula disapproves and wants her to settle down in Transylvania with a nice undead boy and start a family. He travels to New York to bring her home. She wants to stay and live a normal life. That’s pretty much it. (In fact, the “surprise” ending is nearly identical to “Dracula and Son”.)

The exotic Bonet is quite beautiful and at least looks like a vampire. She does a brief nude love scene and a long exhibitionistic bathing sequence that was tacked on after principal shooting was over. Unfortunately, she is also a student of the Pia Zadora school of acting. Her flat, lifeless line readings are devoid of any personality or credibility. She did one more turkey after this dreadful film before her acting career was put out of its misery.

The only decent moments are provided by the two veteran thespians. Carradine, though frail and craggy, makes the most of an underwritten part. He grouses about his castle being turned into a hotel and having to wear false teeth. He and Yvonne De Carlo have a few nice moments together. It’s a shame they didn’t make her up to look more like Lily Munster.

This rushed, extremely low-budget production seems preoccupied with cramming in as many disco songs as possible to promote the soundtrack album. Instead of a plot, we follow Nocturna as she goes club-hopping for much of the film.

Most disappointing are the many throwaway ideas that could have been developed into an amusing satire. Jugulia mentions the problem with the poor quality blood in New York due to drugs, pollution and preservatives. There’s a brief meeting of a vampire rights group that’s considering coming “out of the coffin” to rejoin society. And there’s a funny stereotypical pimp vampire who employs blood-sucking ‘hos at his massage parlor. All promising ideas but nothing is done with them.

Dracula’s Family Visit (2006)

This comedy from The Netherlands concerns Dracula and his siamese twin daughters. Sadly, it was not available for review.

Nearly all of these films can be viewed on free archival websites such as YouTube and Dailymotion.

JIM IVERS is an artist, occasional writer and copy editor for publishers that have a nasty habit of going out of business. He lives on the ragged edge of the hurricane-threatened coast of Connecticut and currently writes about genre films in “Mostly Retro”, a horror-SF-exploitation film zine sold through eBay.