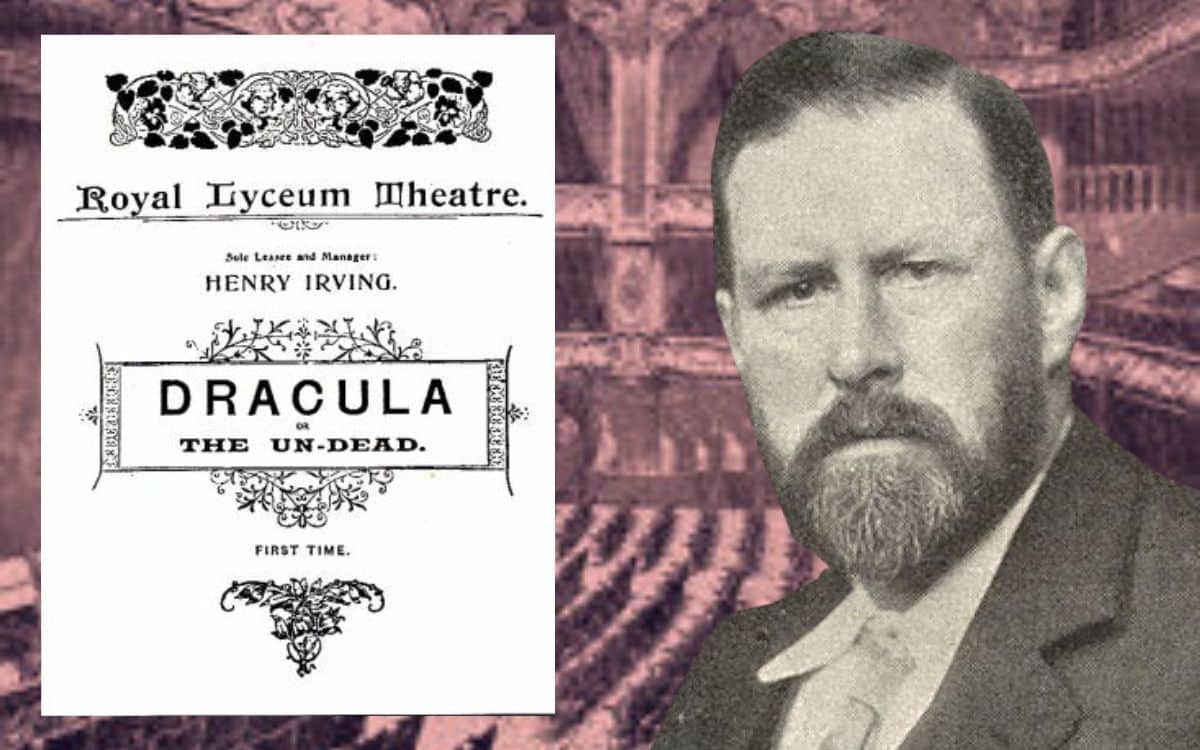

Dracula’s theatrical journey spans from London’s Lyceum Theatre to Broadway. DAVID TURNBULL explores its colourful history and enduring impact

On the front wall of the Lyceum Theatre, near London’s Strand, there is a commemorative plaque, placed there on behalf of the Edgar Allan Poe Society. It was unveiled in February 2008 by Sir Ian McKellen.

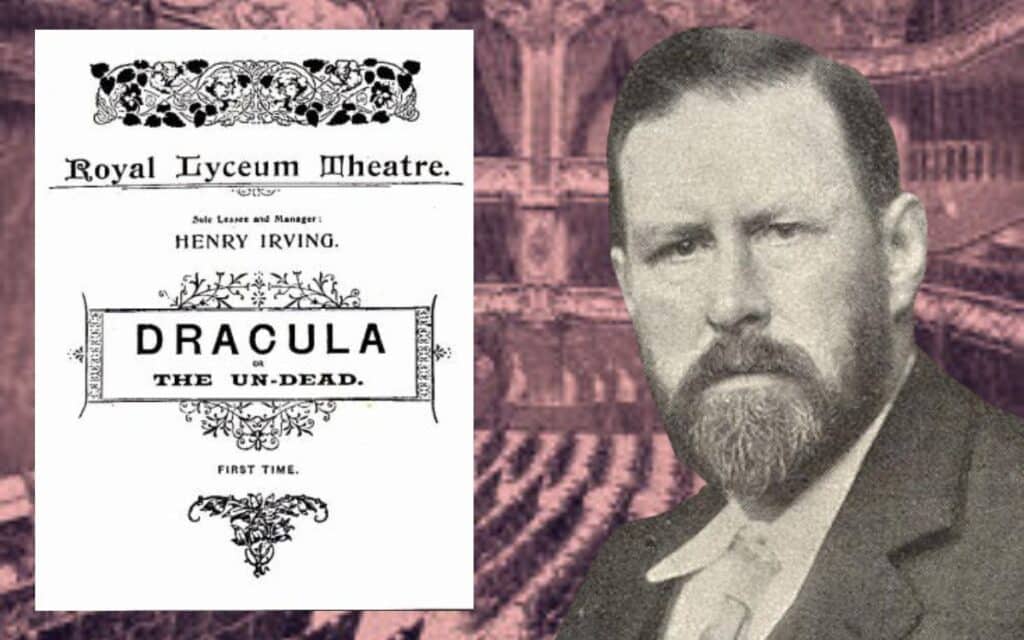

The plaque commemorates two great men who had associations with the theatre. Firstly, the celebrated Victorian actor, Henry Irving, who took over the management of the theatre in the early 1880s, in partnership with the equally celebrated actress, Ellen Terry. Secondly, Dracula author Bram Stoker, who was Irving’s personal assistant and the theatre’s business manager.

Stoker is said to have idolised Irving. But Irving could be a hard taskmaster, and Stoker is also said to have had an underlying fear of him. It is that combination of admiration and unsettling awe that partly inspired Stoker’s description and characterisation of the undead Carpathian Count in his novel.

Inspiration from Gothic Horror

Dracula was written during Stoker’s time at the Lyceum. Not far from the theatre were the narrow lanes leading off from Fleet Street, where Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest created the Penny Dreadful characters Sweeney Todd and Varney the Vampire. The latter was another of Stoker’s influences.

The Lyceum itself had quite a history with gothic horror. In 1823, when it was known as the English Opera House, it staged Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein by Richard Brinsley Peake, the first dramatisation of Mary Shelley’s horror classic.

Two years earlier, in 1820, it had staged The Vampyre; or, The Bride of the Isles by James Planché. The play was based on The Vampyre by John Polidori, also written in the famous chateau on the shores of Lake Geneva where Shelley created her iconic monster. This tale also influenced Stoker’s Dracula.

In the 1880s, The Vampyre was the inspiration for Gilbert and Sullivan’s send-up of the Victorian gothic melodrama in their comic operetta Ruddigore, performed at the nearby Savoy Theatre. An actor who regularly appeared in theatrical performances of Gilbert and Sullivan’s work was Richard Mansfield.

Mansfield’s career took a different turn when he was cast in the lead role in Thomas Russell Sullivan’s (no relation) theatrical adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde. The show premiered at the Madison Square Theatre in New York in 1887.

Irving brought it over to the Lyceum the following year. Its run coincided with the Jack the Ripper killings in Whitechapel, and Mansfield’s portrayal of the monstrous Mister Hyde was so convincing that he was at one point considered a potential Ripper suspect.

The First Stage Adaptations of Dracula

Meanwhile, Stoker was busy writing Dracula. An early stage appearance at the Lyceum came about when he arranged a one-off theatrical reading of the novel shortly after its publication, in order to obtain its theatrical rights.

But it wasn’t until Hamilton Deane arrived on the scene that the notion of an actual Dracula stage play began to develop. Born in 1880 in the same part of Ireland as Stoker, Deane’s mother had been a friend of the Stoker family in her youth.

Deane joined Henry Irving’s theatrical troupe in the late 1890s while still in his teens. Fascinated by Dracula, he wrote the first draft of a stage play and persuaded Irving to allow him to set up a dress rehearsal.

Irving was less than impressed with the outcome and described the effort as being “only fit for the waste paper bin”. Far from being discouraged, however, Deane nurtured his idea.

By the 1920s, he had established his own theatrical troupe, The Hamilton Deane Company, and was ready to return to the project. Irving had died in 1905 and Stoker in 1912.

Deane was aware that Stoker’s widow, Florence, had successfully sued German filmmaker F. W. Murnau for the unauthorised use of the Dracula plot in his classic 1922 silent horror Nosferatu. Keen to avoid a repeat, he sent an updated draft of the play to her and, to his relief, won the official sanction of the Stoker estate.

Under the 1843 Theatres Act, the play had to be submitted to the Lord Chamberlain’s office for approval before it could go into production. Several scenes were censored, including Dracula’s death scene, but the play itself was eventually given the green light.

Dracula’s American Success and Legacy

It premiered at the Grand Theatre in Derby on 15 May 1924, beginning its extensive tour of provincial theatres. Deane himself played the role of Van Helsing. While not critically acclaimed, the play was very successful, attracting large audiences.

Its first London run was at the Little Theatre in the Adelphi, just off the Strand, and only a short walk from the Lyceum. It was such a success with London audiences that it then had runs at several theatres with much bigger capacity, including the Duke of York in St Martin’s Lane and the Garrick in Charing Cross Road.

While Dracula was garnering its success, Deane was contacted by another playwright, Peggy Webling, who had written a new stage version of Frankenstein. Deane agreed to take this on as the next project for his production company, playing the role of Frankenstein’s Monster himself.

Meanwhile, he had reached an agreement with American stage producer Horace Liverwright for a version of Dracula, adapted for American audiences by John L. Balderson, to be performed in New York.

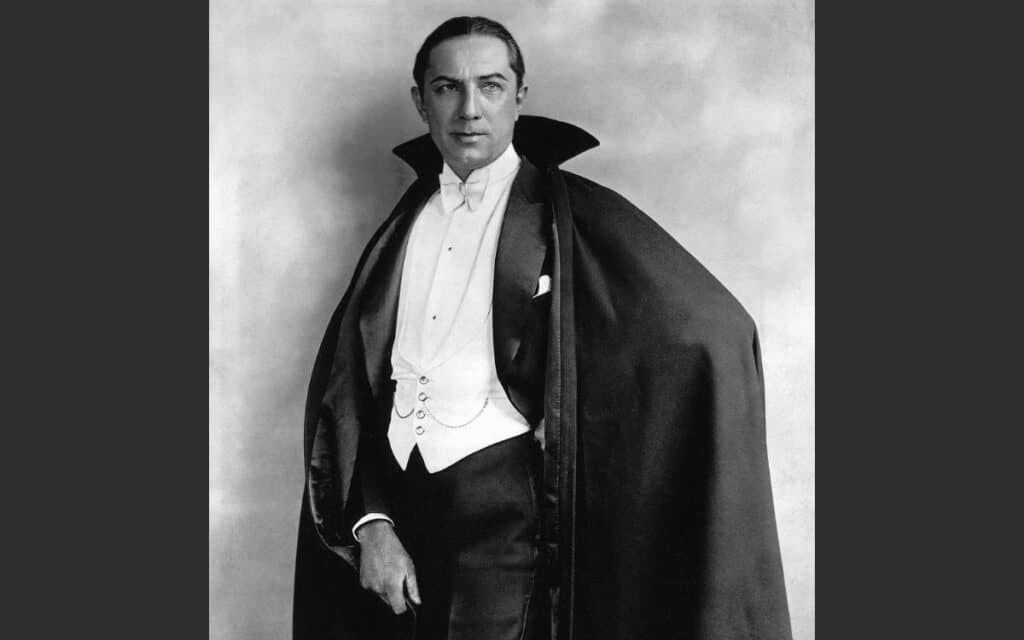

The play premiered at the Fulton Theatre and ran for 261 performances before moving to Broadway, where an unknown Romanian actor called Bela Lugosi assumed the role of Dracula. Based on the New York success, Liverwright set up a touring version of the play with Raymond Huntley, one of the actors who’d played Dracula in the British version, assuming the lead role.

Lugosi, meanwhile, took the play to the West Coast and California, ultimately being cast, along with Edward Van Sloan who played alongside him as Van Helsing, in the classic 1931 Universal Studios version, which is based on the stage play rather than Stoker’s original novel.

Keen to build on Dracula’s American success, Hamilton Deane tried to repeat the UK Frankenstein follow-up by seeking to reach an agreement with Liverwright for a New York adaptation of Webling’s Frankenstein play.

This project never got off the ground. However, when James Whale was engaged by Universal as director of Frankenstein, it was Webling’s play which formed the basis for the big screen adaptation.

London, however, wasn’t yet finished with the Dracula stage play. In the 1930s and 40s, Bela Lugosi had become a huge star playing Dracula and other horror characters on the big screen.

By the 1950s, his career was on the wane and he was deeply in debt. The only roles he was being offered were in Universal Studios’ Abbott and Costello parodies – Abbott and Costello Meet Dracula, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, Abbott and Costello Meet the Monsters, etc.

Although in his late 60s, he jumped at the chance to reset his career when English theatrical producer John Mather approached him to come to the UK for a revival of the play. A cast was assembled.

Rehearsals began in rooms above a pub in Kensington and then moved to The Duke of York’s Theatre on St Martin’s Lane, where Deane’s original play had been performed over two decades earlier.

The play premiered in Brighton, and an arduous tour of provincial theatres zigzagged across the country. While Lugosi was given the Hollywood star treatment by local dignitaries and journalists wherever he appeared, the play itself didn’t go as well as hoped.

John Mather, who had once worked at the Garrick Theatre, had entered into a gentleman’s agreement proposing that Lugosi’s Dracula would have its West End debut there. However, no contracts were actually signed, and when the Garrick decided to extend the run of another play starring a young up-and-coming actor called Richard Attenborough, the plan fell through.

It was in Derby, the city where the Dracula play saw its first public performance, that Lugosi, demoralised and exhausted, told Mather not to book any more dates because he wanted the tour to end.

Strapped for cash and needing to earn enough to book tickets for himself and his wife to travel back to the States, he accepted a film offer from Nettlefold Studios in Walton on Thames. The film in question was Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire.

It must have been particularly galling for Lugosi to realise his attempt to escape the Hollywood parodies ended with another appearance in a parody vampire film. Lugosi must have had hopes that a successful run in London’s West End would lead to a triumphant Broadway revival.

However, it would be almost 30 years before Hamilton Deane’s play would once more be performed in the Big Apple. The 70s revival starred Frank Langella as Count Dracula and ran for 900 performances to great acclaim. He was succeeded in the role by Raul Julia.

Langella also appeared for a short run of the play in London. The Universal Studios movie version, released in 1979, was filmed at the UK’s Shepperton Studios as well as at a number of UK locations.

Alongside Langella as Dracula, the film version boasted Laurence Olivier as Van Helsing and Donald Pleasence as Jack Seward. The film also provided an early role for future Doctor Who, Sylvester McCoy.

Over the years, there have been a number of other stage versions of the Dracula story, including one by Scottish playwright Liz Lochhead, which premiered coincidentally at Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum Theatre in 1985.

In 2022, a stage version of Stoker’s short story Dracula’s Guest, adapted, produced, and directed by James Hyland, was performed at the White Bear Theatre in Lambeth’s Kennington Road. There has even been a Dracula musical.

But none have had the lasting impact of the play first envisaged by a young Hamilton Deane when he worked for Henry Irving alongside Stoker himself.

Have you seen a stage production of Dracula? Tell us about it in the comments section below!