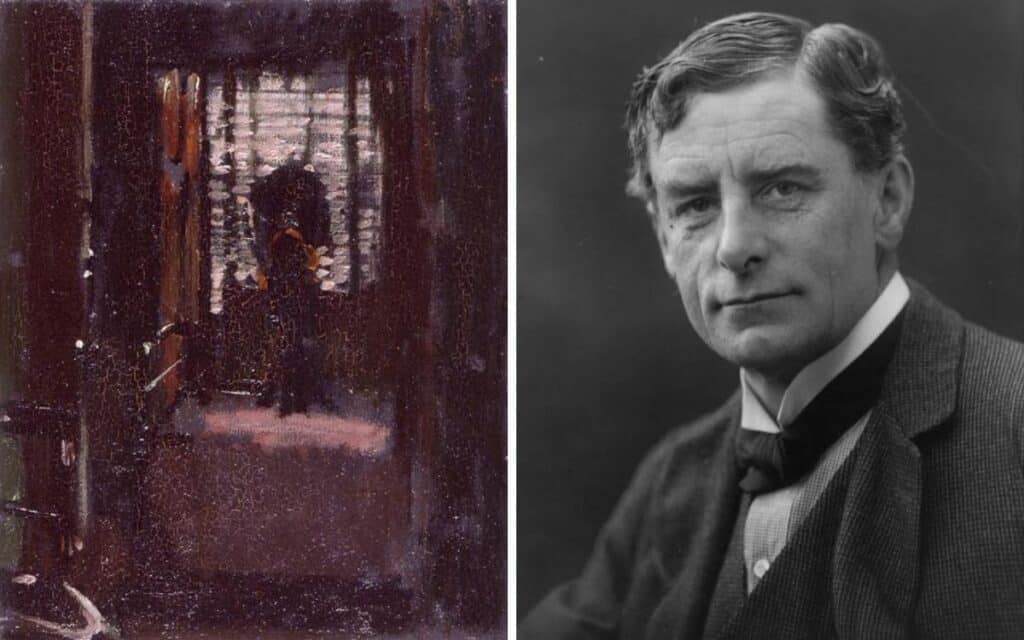

Walter Sickert has been linked to the Jack the Ripper murders, but guest writer GRAHAM KNAPMAN says there’s little evidence to prove the Victorian artist was the infamous Whitechapel killer.

I don’t recall hearing anything about Walter Sickert when I was at school, or even when I was at art college during the late 1970s. Impressionism was all the rage then, and Sickert never quite adopted that style.

We were taught that the Impressionists were reacting against the invention of photography even though we knew that photography was widely used as an aide-memoire.

Our tutors said that it wasn’t in their remit to teach anything else.

Who was Walter Sickert?

In 1980, the art historian, Robert Hughes, presented a documentary called The Shock of the New, which was an attempt to look at the subject of art thematically.

If we attend an exhibition entitled Food in Art today, we might see work by Henri Matisse alongside They Wanted You To Be Destroyed by Tracey Emin, a work referencing Princess Diana’s bulimia.

Hughes was also reported to have said that Walter Sickert’s paintings were an essential part of our visual culture.

He depicted life as he saw it.

The artist only really came to my attention in 2002, after Patricia Cornwall had written Portrait of a Killer-Case Closed in which she identified him as Jack the Ripper.

Stephen Knight and Mervyn Fairclough had already made that suggestion, but it was Cornwall who was grabbing the headlines. She trained as a journalist and worked for the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Richmond, Virginia.

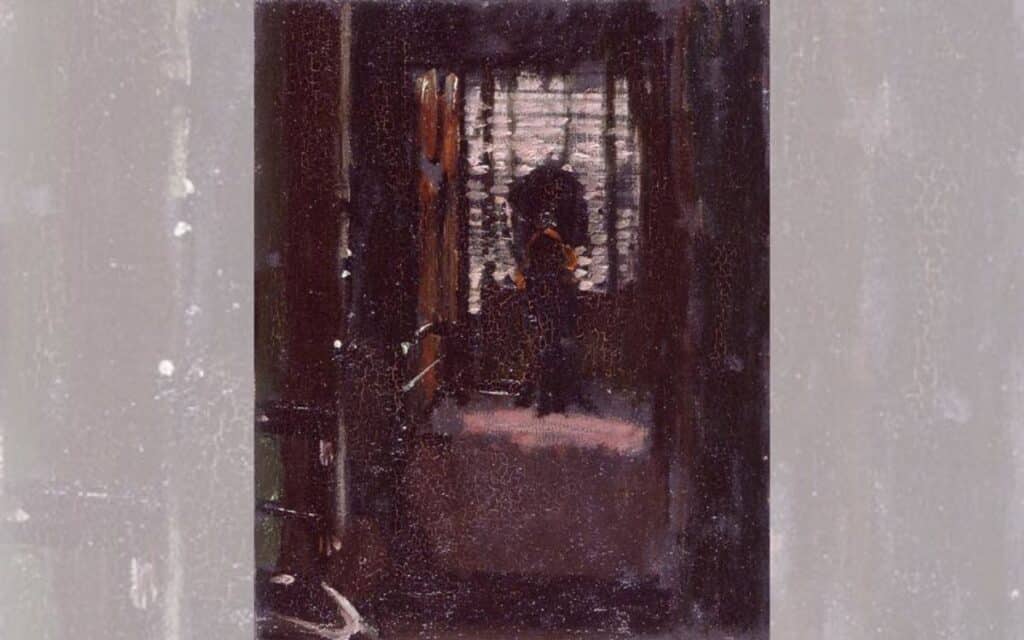

Cornwall pointed out that some of Walter Sickert’s paintings resembled the crime scene photographs. Le Journal is a good example. While he appears to have made use of a photograph taken in the morgue to paint Putana a Casa.

It is widely accepted that Walter Sickert was on holiday near Dieppe at the time.

And it should be noted that hawkers were selling copies of photographs in the vicinity of Whitechapel.

Cornwall also thought that the artist committed the Camden Town Murder in 1907. The evidence for this seems to be that Sickert painted nudes in seedy bedsits, and that he dubbed them the Camden Town series.

He probably thought that the paintings would stand a better chance of selling if they could be linked in some way to the murder.

Sickert himself was attending an exhibition in Paris at the time of the murder.

The facts of the case are simple. Emily Dimmock had arranged to meet Robert Wood in a public house. It then appears that she invited him back to her room because her body was found there next morning.

Wood was put on trial, but there was no evidence to say that he had been present in Emily’s room.

And so he was acquitted.

Sickert took a keen interest in press reports of the case, and he may well have wanted to paint Robert, though there is no evidence that he actually did so.

In Ripper: The Secret Life of Walter Sickert, Cornwall discusses the possibility that Joseph Gorman was Walter Sickert’s illegitimate son. A claim that is impossible to verify.

Gorman worked with Mervyn Fairclough on a book called The Ripper and the Royals.

I wanted to write a play in which Walter Sickert was centre stage. In Tea with Sickert, he is thinking about the time that he was mistaken for Gentleman Jack. He also relates how he rented a room that had once been rented by a Ripper suspect.

Manchester Art Gallery owns a painting by Sickert entitled Jack the Ripper’s Bedroom.

The artist admitted to friends that he suffered from bouts of depression, and I can well imagine how people living in the Whitechapel during the Autumn of 1888 might have had what we now call PTSD.

Tea with Sickert is on at the Etcetera Theatre in Camden, London, in May 2024. The play will then be presented as part of the Edinburgh Fringe.

Tell us your thoughts on this article in the comments section below!

GRAHAM KNAPMAN is a playwright with a keen interest in history and the paranormal. He has a degree in Social Science from the Open University.