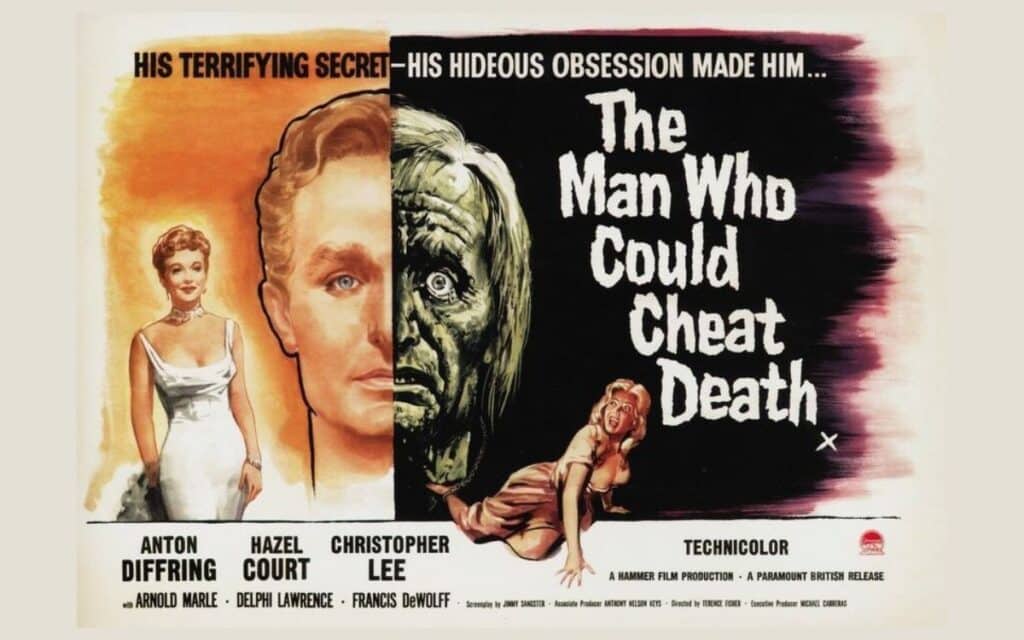

The Man Who Could Cheat Death 1959 remains a routine Hammer Horror despite its legendary director and stars, says TERRY SHERWOOD

TITLE: The Man Who Could Cheat Death

RELEASED: 1959

DIRECTOR: Terence Fisher

CAST: Anton Diffring, Hazel Court, Christopher Lee, Arnold Marlé,Delphi Lawrence and Francis de Wolff.

The Man Who Could Cheat Death 1959 Review

We have all tried to drink from the fountain of youth in one form. Society makes operations, injections and various regimens acceptable often ridiculing when they go wrong. Blending the internal vampire-like quest to stay young and beautiful with that of a scandal-ridden Victorian thriller comes the Hammer Film The Man Who Could Cheat Death 1959.

This Technicolour processed rather talky picture was directed by Terence Fisher with the surprising Anton Diffring in the lead role.

Diffring, who is a neglected genre actor, has the likes of Hazel Court and Christopher Lee to play off of. Lee particularly gives a solid turn in a seemingly effortless performance showing he can play a good character. Unfortunately, they are all saddled with a Jimmy Sangster adapted screenplay from the play The Man in Half Moon Street by Barré Lyndon that still reads like a play.

Paris by Night

The story takes place in Paris, France in 1890. Dr. Georges Bonnet (Anton Diffring), a doctor and sculptor, abruptly ends a party he is hosting. Georges harbours a secret; though he appears to be in his mid-30s, he is actually 104 years old and has kept his youth and vitality through gland transplants every 10 years.

Professor Ludwig Weiss of Vienna (Arnold Maria), co-discoverer of this anti-ageing process, is three weeks late in arriving at Georges’ home to perform the latest transplant. As a result, Georges must drink a steaming green elixir every six hours to stay young. Weiss has had a stroke immobilising his left arm making him unable to perform the operation. Weiss proposes finding another doctor that he will guide.

Through all this floats Janine Dubois (Hazel Court), who was a former lover of Georges. Dubois comes back into his life on the arm of Gerrard, who is in love with her. Dubois wonders why a statue of her had not been finished only to find the work completely hidden behind a curtain.

The film events proceed with Georges’ search for another doctor. He also ends up having to conceal his secret by killing those that find out including the former figure model who happens to be in love with him. Georges settles on Dr. Pierre Gerrard (Lee) who agrees to do the work later to have second thoughts on moral grounds.

“A Lift To Bristol?”

What makes this rather routine film interesting is the actors on the screen. Hazel Count as Janine Dubois in one of her best roles besides the Poe films is regal and lovely when on camera. Court projects the right amount of sensuality for a film of this type simply by walking into the room and turning her head to speak. One moment is some embarrassment when a potential buyer of Georges’ work finds the missing statue, which is a revealing bust. The buyer gazes at the work admiringly only to meet the gaze of Janine whom he recognises as the subject. The embarrassment ends when the buyer sheepishly replaces the covering over the work in true puritanical tradition.

Naughty notes regarding this moment is that the statue used in the film is an actual model of Hazel Court’s torso. The film had an excised nude scene with Diffring’s character sculpting Hazel Court. The edited moment is still in the finished print with obvious frame and angle adjustment yet the idea is still clear. Court was paid a huge amount of extra money saying she did the shot with a limited crew and because it was not gratuitous. The scene did appear in European versions yet to be placed in the present versions of the film unlike the infamous assault scene from Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed 1969.

Still Life

The lead role of Bonnet played by Anton Diffring was originally offered to Peter Cushing, due to just finished work on The Hound of the Baskervilles 1959. The loss of Cushing caused Hammer to threaten legal action against him plus they were in trouble with Paramount Pictures, who were promised Cushing and agreed to partly finance and distribute the film in North America hence its lavish look. The studio relegated the film to the second half of double bills in retaliation

It’s a shame because although Anton Diffring gives a slightly theatrical performance with head turns, profiles and rather scene-chewing voice work, he does have the essential quality of the desperate genius determined to live at any cost.

Diffring’s voice, and diction as well as Christopher Lee’s particularly in the moments when dickering about the operation flow well with both limited action and movement. Unfortunately, limited action does not play well in filmmaking. The Man Who Could Cheat Death 1959 is rather stationary.

Anton Diffring would have been brilliant as Baron Meinster from Brides of Dracula 1960.

Terence Fisher directed this film so the pacing falls to him, however, the Technicolour must have been startling in the late fifties, making it worth a view as a set-piece.

Tell us your thoughts on The Man Who Could Cheat Death 1959 in the comments section below!