TERRY SHERWOOD delves into the career of Croydon-born Horror Star Lionel Atwill and picks his seven favourite portrayals of mad scientists!

Lionel Atwill was born to a wealthy family in Croydon, England, in 1885. He wasn’t blessed by the looks of a matinee idol, but after studying architecture, he became more of a character actor.

Lionel Atwill’s genre career could be split into two portfolios: policemen and/or mad scientists. The common element throughout his career was that the roles were of authority figures; be they on the right or wrong side of the law.

One of the staple images that crosses over between horror and science fiction is the ‘mad scientist.’ This particular character could manifest as part of mainstream cinema; for example, the sinister pharmaceutical companies films yet to come. ‘One note’ madness is often delivered by today’s actors either by simplicity of plot or easy audience appeal. The multilayered portrayal is not a factor. Let the games begin:

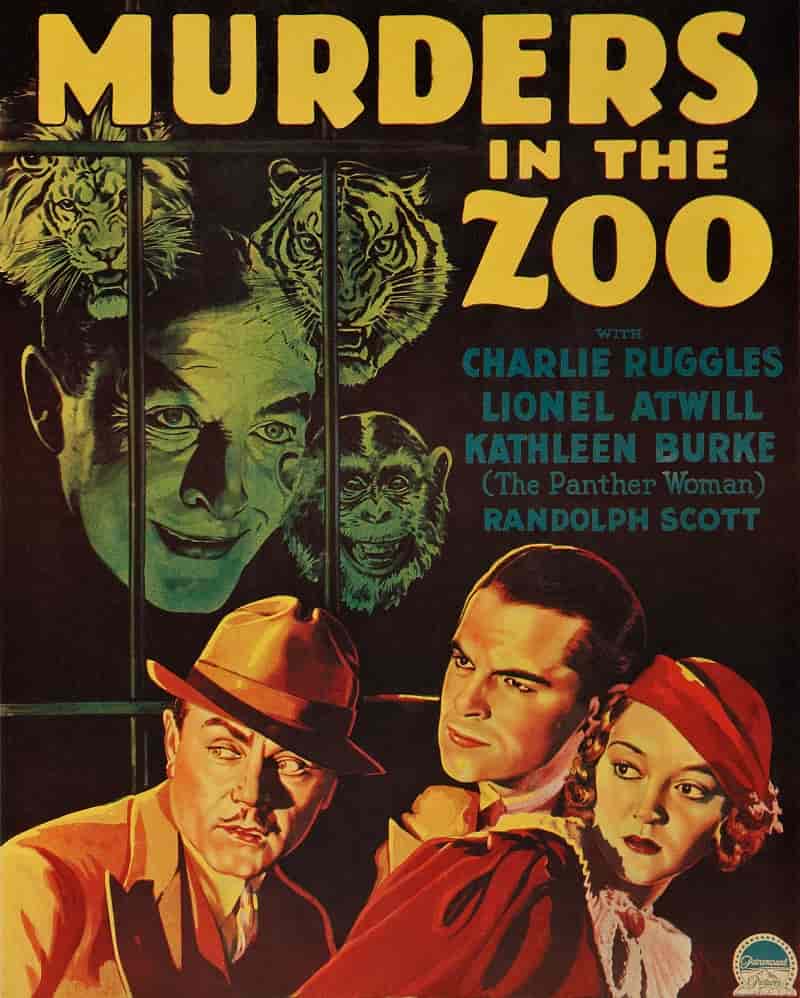

1.) Murder in the Zoo (1933)

Hard to beat the brutal death on the bridge at night in the zoo or the final payback with the python for intensity. Eric Gorman is sadistic to all on screen while cold-bloodedly dispatching victims in various ways. I only wish Charles Ruggles character would have been a victim as I loathe Ruggle’s on screen and irritating comic relief.

2.) The Vampire Bat (1933)

The role of Dr. Otto Von Nieman in this picture is the most significant depiction of lunatic logic. Colin Clive in Frankenstein (1931) utilized a style of controlled frenzy, punctuated by bouts of arrogance and resolution, captured in the famous cut line, “I want to know what it’s like to be a god.” This is delivered in a laughing way to the heavens that is both mocking and triumphant over rational thought. Atwill’s read on the character is different; as is his quality of madness. In the film, he shows no remorse. There is only a finality that he had done the deed, as he spouts off his claims to a shocked Fay Wray.

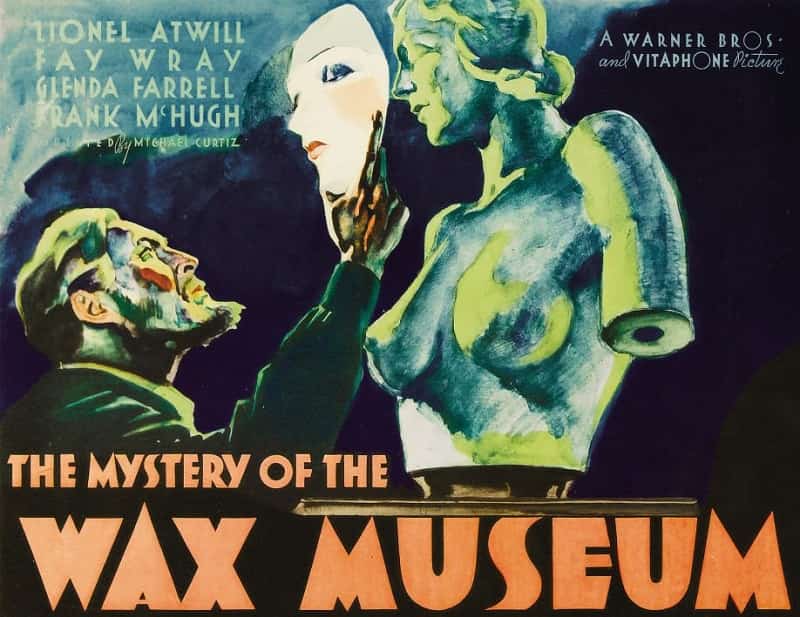

3.) Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933)

Atwill changes the face of madness to obsession to re-create and preserve art. We are treated to a grotesque scene as wax figures slowly dissolve in the heat of a fire. Tame today, yet symbolic, as the figures melt their faces elongate and distort we see the destruction of the human form. Here is the raw material for the re-creation.

4.) Man Made Monster (1942)

A surprisingly-good quickie made by Universal to see if Lon Chaney Jr could do a lead role. Luckily, he is teamed with Attwill, who is at his nefarious best doing what he can to corrupt and get his experiment completed. Some gleeful close-ups of Atwill as Dr Paul Rigas menacing Anne Nagel. The eyes reveal the depth of the lunacy, along with voice inflection. Not quite a textured portrayal of the scientific madman but still one of the actor’s best. Unfortunately, it set the template for the cliché mad doctors to come.

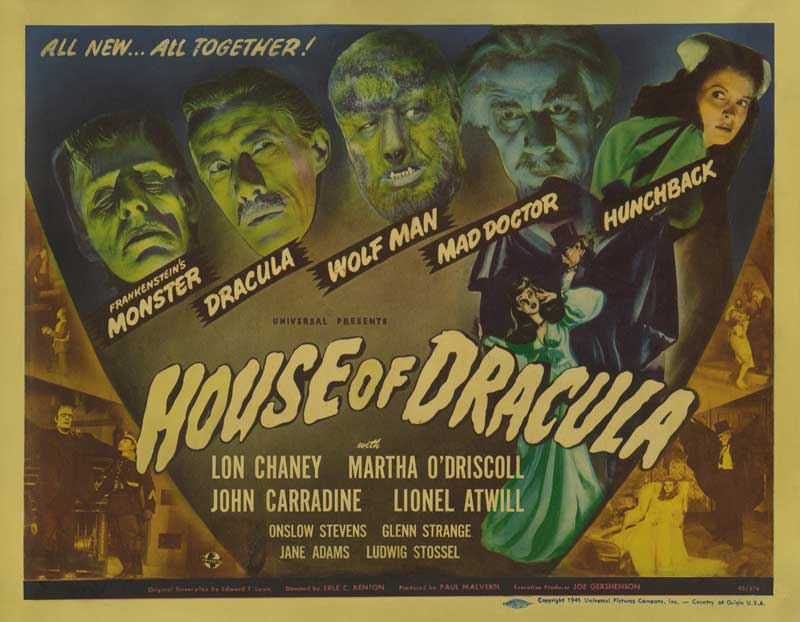

5.) Ghost of Frankenstein (1942)

The role of Dr Bohmer is one, while not his best, is a utility part in the script. There had to be some way of making the plot move forward and putting Ygor’s brain into the body of the creature. Atwill’s Dr Bohmer is one dimensional. He is forced to be used in the proceedings by his past transgressions. Still, an interesting look at a trapped man who will do anything to vindicate himself.

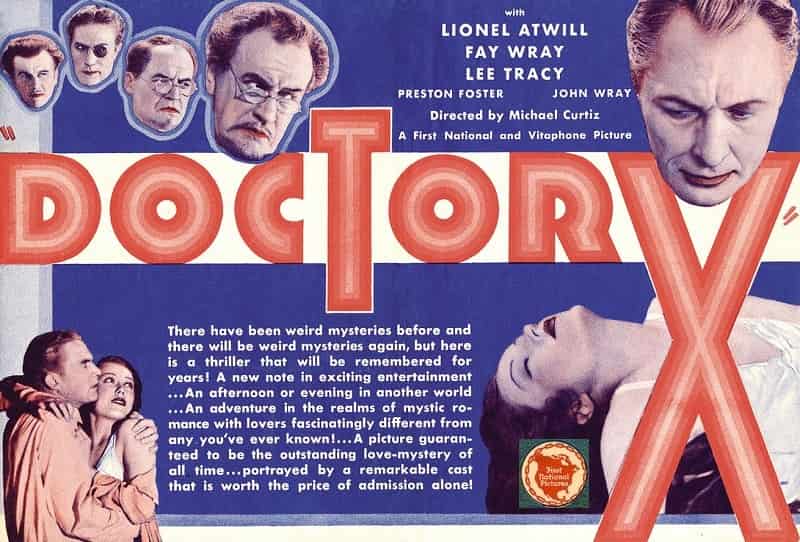

6.) Dr. X (1932)

Warner Brothers two strip Technicolor feature before the superior Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). Atwill appears as Doctor Xavier – who is more like a medical consultant on a ghastly ‘moon murders’ case. The best part? Atwill’s screen time is high as he comes off as being his elegant, erudite self. The on screen moments with Canadian born Fay Wray are wonderful in interplay and suggestion. One can see the strong acting skills with the good cast if not non horror players and a non horror director in Michael Curtiz. Not a lot of insanity here, so to speak. More scientific melodrama tackling taboo themes for the time.

7.) Mad Doctor of Market Street (1942)

Dr Ralph Benson seems like an afterthought in this picture. Atwill appears in the beginning and then comes back in later when the action has moved to the Island. Benson seems to be obsessed with raising the dead which all comes into play later which is not new. The director decides to capitalize on Atwill’s mad glare by employing several times in the picture a point of view shot of him approaching his would be victim with a gas mask which he puts over the camera lenses.

My first contact with Atwill came out of the long playing record called An Evening with Boris Karloff and his friends. I purchased it from a bin in an Ottawa department store because it had a hole punched out of the record cover. This brought its price to a grand total of $2.00. I still have that record. I listened to it many times, including the monologue that Atwill spoke regarding his unfortunate childhood encounter with the Frankenstein monster in Son of Frankenstein (1939). I used it as an audition piece along with Colin Clive’s creation speech from Frankenstein (1931). It was many years before I saw the Son of Frankenstein on television and the full impact of the speech.

Madness done well on the screen adds much to a story as long as it is nuanced with other aspects of character. Despite what we see in the political and social arenas today, no one is truly that bad. Just another aspect of human.

You can read more about Lionel Atwill and his off-screen activities here: Lionel Atwill, Horror Star’s Hollywood Sex Scandal

Do you agree with Terry Sherwood’s choices? What are you favourite Lionel Atwill horror films? Tell us in the comments section below!