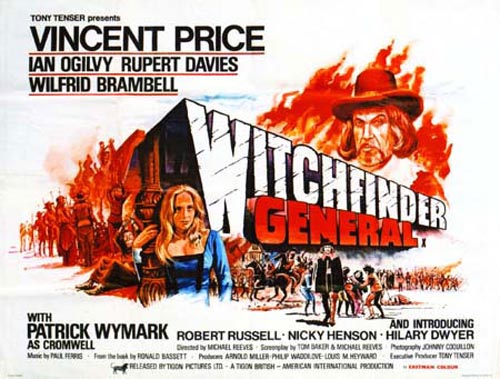

BARRY McCANN goes behind the legend to discovery the reality of England’s most notorious witchfinder, Matthew Hopkins, who was portrayed by Vincent Price in Witchfinder General

There are some figures in history who have become mythologised by folklorists and writers, mainly when their real life stories contain factual gaps filled by speculation which, in turn, has become accepted as popular truth. Dick Turpin and the Pendle Witches are two examples of this. But, perhaps, the most enigmatic is Matthew Hopkins, the notorious Witchfinder General.

Who was Matthew Hopkins?

Matthew Hopkins (1620–1647) began his witch-finding career began in 1645 with assistant John Sterne, claiming to have the backing of Parliament (which he did not) and is believed to have been responsible for the deaths of 300 women over the course of two years. The pair extracted confessions with methods such as sleep deprivation, or the swimming test where those who floated were declared witches. Hopkins also looked for the Devil’s mark, usually a mole or birthmark. If no such marks were visible, then the accused were pricked with knives and special needles to find “invisible” ones.

Hopkins operated mainly in the counties of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk, and occasionally in Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire, and Huntingdonshire, charging 20 shillings a town for his services. His career came to an end when he died at his home in Manningtree, Essex, on 12 August 1647, probably of pleural tuberculosis. Legend has it that he was subjected to his own swimming test and executed as a witch, but the parish registry at Church of St Mary, Mistley Heath, confirms was interned there.

Matthew Hopkins became the subject of Ronald Bassett’s 1966 novel Witchfinder General, a fictional revenge thriller that bore little resemblance to the true story. Tony Tenser bought the rights to the novel and offered the project to Michael Reeves, who had just completed Tigon’s The Sorcerers (1967), starring Boris Karloff. Indeed, Tenser reputedly thought Karloff could take the part of Hopkins, before Reeves pointed out the actor was too infirmed and would be unable to ride a horse.

Reeves and co writer Tom Baker originally had Donald Pleasence in mind to play Matthew Hopkins as “ineffective and inadequate… a ridiculous authority figure.” However, once American International Pictures became involved and insisted on Vincent Price being cast, Reeves and Baker had to rethink their original concept as the tall, imposing Price would have to be more authoritative.

Reeves made no secret that Price was not his choice and was determined to reign the actor’s usual infusion of camp. This caused clashes, which Price later commented “He would stop me and say, ‘Don’t move your head like that.’ And I would say, “Like what? What do you mean?” He’d say, “There – you’re doing it again. Don’t do that.”

During one argument, Price reputedly said “I’ve made 92 films. What have you done?” Reeves responded “Two good ones.” However, upon seeing the completed film, Price declared it to be one of the best performances he had ever given and realised what Reeves was trying to achieve.

There was also a problem with the original ending in which Ian Ogilvy was to have pushed Price on to a vat of burning coal, engulfing him in flames. The required pyro technique could not be staged in the end, so it was suggested that Richard Marshall (Ogilvy) should hack Matthew Hopkins to death, as the Nicky Henson character bursts in and finishes the job with his flintlock. A now insane Marshall goes for his friend and is himself shot dead.

However, Henson pointed out to Reeves that a flintlock is not a revolver and has to be reloaded after each shot. Reeves, on the spot, decided to have Marshall ranting “You took him away from me” and the camera freeze on Sara screaming, creating one of the most memorable endings in horror film history

Reaction to Witchfinder General 1968 film

Upon release, the film’s violence inevitably attracted negative reviews, particularly from playwright Alan Bennett who attacked it as “the most persistently sadistic and morally rotten film I have seen. It was a degrading experience by which I mean it made me feel dirty.”

Reeves responded with “Surely the most immoral thing in any form of entertainment is the conditioning of the audience to accept and enjoy violence … Violence is horrible, degrading and sordid. Insofar as one is going to show it on the screen at all, it should be presented as such – and the more people it shocks into sickened recognition of these facts the better. I wish I could have witnessed Mr. Bennett frantically attempting to wash away the ‘dirty’ feeling my film gave him. It would have been proof of the fact that Witchfinder General works as intended.”

AIP released it in the States as The Conqueror Worm to tie it in with their cycle of Poe movies previously made with Vincent Price. It went on to gross 10 million dollars, much to everyone’s surprise. But, then, it is in many ways a western and would connect with the American psyche as such. Apart from horse riding chases, the plot revolves around a hero returning to the ranch, only to find it has been raided by outlaws and his woman violated. So off he goes to hunt them down and exact revenge. Comparisons can be drawn with such westerns as Rancho Notorious and The Searchers.

More recently, the story of the making of Witchfinder General became the subject of a radio play. Vincent Price and The Horror of The English Blood Beast by Matthew Broughton, first broadcast in March 2010 on BBC Radio 4. Vincent Price played by Nickolas Grace.

East Anglia gets Witch Fever with Matthew Hopkins!

(Originally Published on Spooky Isles 21 July 2015)

JOSIE PALMER looks at how a lawyer from East Anglia whipped up hysteria over witches in the 1600s

The witch-fever that gripped East Anglia for 14 terrible months between 1645 and 1646 was a symptom of the nervous tension of a nation at war with itself.

Long before the struggle between King and Parliament led to open war in 1642, the people of the Eastern counties had taken sides.

This area was solidly Puritan, rabidly anti-Catholic and swayed by the preachers whose mission was to seek out the slightest whiff of heresy.

As the war dragged on, fear and suspicion mounted.

As so often happens, such popular hysteria produced a figurehead.

In this case, it was a man who would be remembered by history as the Witchfinder General.

He was, in fact, a lawyer from East Anglia, named Matthew Hopkins.

Though the number of supposed witches put to death by Hopkins will never be known for certain, it was probably in the region of 400 – more than a third of the total number executed in two centuries of English witch-hunting.

Hopkins had 68 people put to death in Bury St Edmunds, and 19 hanged at Chelmsford in a single day.

The Witchfinder is still remembered with horror, yet he could not have carried out his persecutions without the active cooperation of the local population.

The witch-hunts followed a pattern all too familiar: popular denunciation, interrogation in a cell, the death by hanging.

Records of Hopkins’ career in witch hunting are obscure, but it appears to have come about after he moved to Manningtree in Essex in 1644.

Not a great deal is known about Matthew Hopkins’ early life. It is thought that he was born in Little Wenham in Suffolk in the 1620s.

He trained as a lawyer but with little professional success. He augmented his salary with the opportunities that witch-hunting offered him. His new career started near his home in Manningtree in 1644, where he examined his first witch at the Thorn Inn, Mistley.

Accusations of witchcraft started to spread throughout East Anglia, spurred in no small measure by Matthew Hopkins’ actions.

In Sudbury 117 people were tried and examined, and in Norfolk 40 women were tried and examined by the Norfolk Assizes in 1645.

Eight women were tried and at least five executed in Huntingdonshire by the summer of 1646. Independent borough jurisdictions were also busy during this period, trying and examining mostly women for witchcraft.

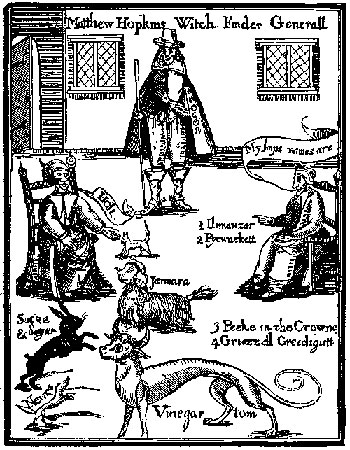

Hopkins believed that witches fed their ‘familiars’ (animals that would accompany them in their evil practices) with their own blood; by keeping the witch under guard it would ensure that their familiars could not feed from the witch, thereby depriving the witches of their magical capabilities.

Matthew Hopkins believed that witches had a third nipple just for feeding their familiars.

The layman might easily mistake these witch’s marks for a wart, a mole or even a flea bite; to Hopkins these were the Devil’s marks, insensitive to pain, incapable of bleeding, and easily detectable by jabbing with a needle.

Doubting onlookers were convinced when they saw a needle disappearing into flesh without a sign from the victim.

What the onlookers didn’t realise was that the needles were often retracting into spring-loaded handles.

Once the witch’s mark was discovered on the suspect’s body, all that remained was to obtain a confession.

Methods of torture like the rack were illegal but starvation, solitary confinement and being tied cross-legged for days at a time were effective; being walked up and down in a cell for five days and nights without rest made most people confess to anything.

When Matthew Hopkins swore on oath that four familiars – a white dog, a greyhound, a polecat and a black imp – had visited Elizabeth Clarke in her cell, she did not deny the charge. She even confessed to having slept with the Devil often.

A favourite confessional torture of Hopkins was the infamous ‘swimming’ test.

The suspect’s limbs were bound together and then they were lowered into a pond by ropes.

The principle was simple – if the victim sank and drowned, they would be innocent and in heaven; if they floated they would be tried as a witch.

Although much of Matthew Hopkins’ career as a Witchfinder is well recorded, his death is still somewhat of a mystery.

One account, written by William Andrews, a nineteenth-century writer of Essex folklore, suggests that Hopkins was himself accused of being a witch. Andrews puts forward the case that Matthew Hopkins was charged with stealing a book containing a list of all the witches in England, which he purportedly obtained by means of sorcery.

Hopkins declared his innocence but an angry mob forced him to undergo his own ‘swimming’ test. Some accounts say he drowned, while others say he floated and was thus condemned to be hanged. No records of his trial exist.

Another local legend has it that Matthew Hopkins’ ghost haunts Mistley Pond. An apparition wearing seventeenth-century clothes can apparently be seen roving the locality, particularly on Friday nights near to the Witches’ Sabbats. There have also been reports of Matthew Hopkins’ ghost haunting the White Horse Inn in Mistley.

Whatever the truth of Hopkins’ death, he was a controversial figure even in his own lifetime. He, and other witch hunters, were able to carry out their work with impunity during the power vacuum and chaos of the English Civil Wars.

During the Restoration, witch hunts and trials petered out and the last witchcraft execution was carried in Exeter when Alicia Molland met her death in March 1684.