Guest writer SARAH PARKIN examines Mary Shelley and how England’s greatest gothic horror novel came to be and its affect when it was released

First off, we learn how the author’s parents had a strong influence on the making of the masterpiece.

What comes to mind when you hear the name of Mary Shelley?

There’s at least one obvious answer.

The woman who gave the world Frankenstein and wife of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley is one of few women whose marriage to another writer has not overshadowed her own literary achievement.

That’s hardly surprising – the 1818 classic is a major contribution to the Gothic genre and arguably the first science fiction novel in English literature.

It’s also gripping, original and genuinely frightening. Still, it wasn’t shaped in a vacuum, and neither was its creator. Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, as she was born, was surrounded by literary and political influences that can be traced throughout her remarkable career, and nowhere more clearly than Frankenstein.

By far the most significant influences were her parents. Mary’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, died of puerperal fever 11 days after giving birth, but remained an important presence throughout her daughter’s childhood.

The author of an array of treatises including A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and the novels Mary and the unfinished Maria; or, The Wrongs of Woman was renowned for her radical views and has since earned a place in the history of feminist thinkers.

However, her unconventional lifestyle – including her illegitimate daughter from an earlier relationship – was placed in the spotlight when her husband, Mary’s father William Godwin, published a memoir of her which spoke candidly of her sexual history.

The scandal which became attached to Wollstonecraft’s name persisted throughout Mary’s lifetime, but she was also keenly aware of her mother’s literary achievements: she was as much of a presence as her portrait staring down from the wall in Godwin’s study.

Godwin himself had achieved some success as a writer.

The controversial treatise An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) was followed by six major novels, the first of which was Things as They Are, or The Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794), but throughout Mary’s infancy and early childhood his fortunes declined. He had been known as one of the foremost thinkers of his circle of liberal reformists, and insisted on high intellectual standards for his children.

As a result, Mary was multilingual, well read and steeped in mythological and religious traditions.

Though his financial circumstances got worse and worse over the years and his fame faded somewhat, his circle remained large and as a result Mary came into contact with major figures including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles and Mary Lamb and, of course, Shelley.

Mary grew up surrounded by philosophical and literary heavyweights whose views she took on board, not least the father she adored.

Looking at the work of Mary’s parents, common threads start to appear that are clear in her own work. Godwin’s Caleb Williams is a dramatic Gothic novel, discussing the abuse of power by tyrannical governments by focussing on a servant persecuted by his master when he discovers his dark secret.

The Wrongs of Woman sees Wollstonecraft using Gothic tropes to represent the suppression of women in the tale of a wife locked in an asylum by her husband.

It’s no surprise that both belonged to the radical intellectual movement which admired the French Revolution – freedom from the oppression of political institutions dominates their thought because that power is so often and so easily abused.

One of the central themes of Frankenstein is the responsibility that comes with the acquisition of power; proof, as though it were needed, that Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was fully deserving of both her parents’ names.

Teenage Mary Godwin meets Percy Shelley

11 November 1812 proved a milestone in Mary Godwin’s life.

A brief return to her father and step-mother’s house from a stay with family friends in Dundee saw her introduction to the Shelleys.

The lives of the couple had already been tempestuous.

Percy Shelley, the son of a Whig MP who later inherited the title of Sir Timothy, had been educated at Eton and Oxford, until his authorship of the atheist tract The Necessity of Atheism resulted in his expulsion from University College in 1811.

Relations with his father, already strained as a result, finally disintegrated later that year when Percy eloped with and married Harriet Westbrook, a 16-year-old school friend of his sister who, as the daughter of a wealthy coffee-house owner, was his considerable social inferior.

Sir Timothy cut off his son’s allowance, and financial problems plagued the couple as Percy continued to write and publish poetry as well as his politically revolutionary tracts.

They moved around a lot, and even spent time in Ireland where Percy aided efforts repeal the Act of Union and ensure Catholic emancipation.

After their return, the Shelleys finally met one of Percy’s idols with whom he had been corresponding for much of that year: William Godwin.

Godwin’s daughter was 15 at the time, and it was to be two years before Mary’s acquaintance with the Shelleys was renewed.

By that time, the couple’s first daughter, Eliza Ianthe, was nearly a year old, but a rift had grown between Percy and Harriet that was never to be healed, and a passionate relationship began to form between Shelley and the daughter of his mentor.

In early summer 1814 the pair met frequently, often at the grave of Mary’s mother Mary Wollstonecraft, and in late July, accompanied by her half-sister Claire Clairmont, Mary and her 22-year-old lover eloped.

This was to be the start of a hectic if brief life together, taking in extensive travel, literary creativity and, of course, financial instability.

By the time they returned to England in September they were all but penniless and Mary was already pregnant – but Harriet was always a constant presence.

She gave birth to Percy’s second child Charles in November 1814, and his letters to his wife demonstrate barely suppressed guilt for abandoning their family: when his grandfather died in 1815 and his immediate financial difficulties eased, he made arrangements to pay Harriet £200 a year for their maintenance.

The relationship was viewed with universal disapproval, even from Godwin, despite his earlier philosophical arguments against the institution of marriage that probably influenced Percy.

Mary’s sister Claire was also a source of tension, her close friendship with Percy causing considerable jealousy on Mary’s part even after Claire had an affair with Lord Byron. The couple’s first daughter died before her first birthday in early 1816, 12 days after the birth of their son, William.

Though Mary does not seem to have begrudged Percy’s support of Harriet – after her eventual suicide Mary supported his efforts to gain custody of the children – their relationship was under constant strain, yet clearly kept intact by strong mutual affection.

By mid-1816, when ‘the Shelleys’ travelled to Lake Geneva to spend the summer with Byron, Mary found herself grieving for the death of one child while trying to raise another, in a relationship with another woman’s husband and facing public recrimination for her unconventional lifestyle – at the age of 19.

Given her mother’s scandalous reputation, having cohabited and had a child with a man out of wedlock before meeting Godwin, Mary would have been even more keenly aware of the position in which she had put herself, and it is in this unique climate of loss, guilt and uncertainty that Frankenstein was born.

Lake Geneva, where Mary Shelley conceived Frankenstein

Of the coterie that spent the summer of 1816 at Lake Geneva, Claire Clairmont must be by far the least renowned.

Among the few who know her name, she is Mary Shelley’s step-sister, a friend of Percy Shelley and one of many lovers of George Gordon, Lord Byron.

It was thanks to her, however, that the group came together at all. Her brief affair with Byron that spring had clearly exacerbated her infatuation – introducing her step-sister to the poet enabled her to arrange for Mary, Percy and herself to stay in a house near the grand villa the poet had leased.

For Mary, who was increasingly known as Mary Shelley although the couple were not yet married, this was one of many complications in her life.

Travelling for the sake of Percy’s poor health with an infant child would have been stressful enough without the controversy that followed them at home and abroad.

Although we don’t know exactly when that summer Claire learned she was pregnant with Byron’s child, nor indeed when Byron tired of her and the affair ended, it’s almost too tempting to suggest that this was another trauma of procreation on the list that inspired Mary’s unique representation of a monstrous birth.

The group found themselves together on the dark, stormy night of June 16th, the atmosphere perfect for a ghost story, when a plot was hatched: instead of telling other people’s stories, they would write their own. Percy struggled to find inspiration and quickly gave up.

Even Byron, who was incredibly prolific all summer, began a vampire novel and abandoned it.

The successful writers were, ironically, the ones who were not yet known. Byron’s physician Dr. Polidori took up the poet’s ideas and developed them into The Vampyre, the short story that catalysed the subgenre eighty years before Bram Stoker put pen to paper for Dracula.

Mary, meanwhile, struggled with her assignment, but refused to give up so lightly.

According to her introduction to the 1831 edition of her novel, several days passed until, after a long night talking of contemporary experiments in galvanism (reanimating dead flesh using electrical currents), she had a peculiar waking dream:

“I saw—with shut eyes, but acute mental vision, —I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away from his odious handywork, horror-stricken.”

She thought she had the beginnings of a short story. Over the next year, with Percy’s encouragement and collaboration, including his frequent alterations and suggestions on the manuscript, it became a full length novel, drawing on the traumas that marked their early relationship.

The first four chapters were written after Mary’s half-sister Fanny Imlay committed suicide, depressed after Mary and Claire’s departure and having learned of her illegitimacy. In November,

Percy’s heavily pregnant wife Harriet also killed herself, breeding lasting guilt for both himself and Mary. When the lovers finally married just a few weeks later, it was in part to help Percy’s suit for custody of his two children by Harriet.

By the time Frankenstein was finished in May 1817, it was built on over a year of painful childbirths and childrearing that shine through in the relationship between creator and creation.

When eventually published in January 1818, with a preface by Percy and dedication to her father William Godwin, Frankenstein didn’t even bear Mary’s name – it was anonymous until the second edition was released in 1822 – but her masterpiece was given to a world that had no idea just how important it would be.

Frankenstein receives mixed reaction

When Mary Shelley published her debut novel in 1818, nobody knew it was hers. The first edition was published anonymously, leaving reviewers free to speculate; though no attempts seem to have been made to name an author, some reviews came close.

“It is formed on the Godwinian manner, and has all the faults, but many likewise of the beauties of that model.” (The Edinburgh Magazine)

It is piously dedicated to William Godwin, and written in the spirit of his school.” (The Quarterly Review)

Comparisons of Mary’s novel with those of her father William Godwin are clearly warranted, although another school of thought suggested that it could be Percy Shelley’s work.

The use of Godwin’s tropes and themes was less important, however, than the revolutionary politics he shared with his daughter, and the potential threat they posed was keenly felt by more conservative voices.

This was an even greater concern given that the book became commercially successful very quickly: it was translated into French as early as 1821 and popularised through a range of melodramatic dramatic adaptations from the likes of Richard Brinsley Peake.

Anxiety about the dangerous influence of the novel on the young and vulnerable, especially in light of its apparent moral ambivalence, is tangible in nearly every surviving review from this period.

Nonetheless, the reviews do generally tend to acknowledge the author’s considerable “original genius and happy power of expression” (Sir Walter Scott), suggesting grudging respect for an aesthetic talent coupled with disquietingly radical attitudes. In fact, the initial reception of Frankenstein was mixed, ranging from outrage and disgust to fascination and qualified praise.

Once the author’s name was released, however, the tone of her critics quickly shifted.

Her colourful private life may have been enough of a deterrent to certain groups in society, but above all, readers were driven by the view of politics as a man’s subject.

Though Mary was tellingly often credited with a “masculine mind”, commentators treated Frankenstein (as they would her later novels) as a ‘romance’ if, indeed, they heeded it at all:

“The writer of it is, we understand, a female; this is an aggravation of that which is the prevailing fault of the novel; but if our authoress can forget the gentleness of her sex, it is no reason why we should; and we shall therefore dismiss the novel without further comment.” (The British Critic)

A great number of critics followed suit. Despite the success of the small print run of the 1823 edition, the bestseller was ignored by many intellectuals for years.

Even the 1831 edition, which had undergone several revisions and finally gained a mass audience, did little to cure this, and the lack of new editions in the following five decades meant that Frankenstein was studied relatively little and valued less. Like so many ground-breaking artists, Mary saw her work met by critics unequipped to judge it.

Around the same time, Mary’s life was becoming even more difficult. Relations with her husband had always fluctuated wildly, but she was left devastated when she suffered another miscarriage in 1822 and, weeks later, Percy drowned off the coast of Italy just before his thirtieth birthday.

After a year with friends in Genoa, she returned to England and devoted her life to her surviving son, Percy Florence, and a career as a professional author.

Much of her life was spent in terse discussions with Percy’s father, Sir Timothy, over the allowance he granted her for his grandson’s upkeep; continuing to write novels and short stories; and in editing and promoting her husband’s poems, assuring the literary appreciation he had largely been denied in life.

She never remarried. By the time she died of a suspected brain tumour in 1851 she was a respected author, but predominantly for her later work.

Frankenstein was, however, as alive as its central Creature.

Stage adaptations continued, and the characters remained in the public consciousness though the novel was out of circulation.

Perhaps this is why its resurgence was so strong: only in the 1880s, when it had come out of its original copyright conditions and the benefits of mass literacy were beginning to appear, that Frankenstein found a truly huge readership.

The first reprint sold more than all the previous editions combined, and from that point it grew into the global phenomenon that has had such impact on the modern world.

Mary Shelley’s later years and legacy of Frankenstein

By the time of her death, Mary Shelley was the respected author of seven novels, at least 23 short stories, and even some children’s literature.

She was also an accomplished biographer, poet and editor of the works of her husband Percy, whose status as one of the major poets of the Romantic period was largely assured by her efforts.

Despite the significance of works such as The Last Man (1826), however, her full importance as a writer is only just beginning to be understood: it’s interesting that, when her later work was more critically acclaimed at the time, it has mostly been forgotten, while Frankenstein’s reputation continues to grow.

It’s one of the most accomplished Gothic novels of the period, borrowing heavily from the conventions pioneered by her father among others, but at the same time its voice is unique. Mary’s own chequered personal life provides themes and preoccupations which are not articulated as strongly by anybody else – her insight into the traumas of childbirth and parenthood, as well as her own struggle to live up to the reputations of her famous parents, shine through in Victor Frankenstein’s struggles to create a human being and then to make a man. The suggestion that the two are not the same is one of the keynotes of the novel.

Science fiction as a genre in English largely owes its existence to Frankenstein, which is probably the earliest and one of the most influential examples.

Even modern writers acknowledge its influence; elements of Shelley’s work have been in detected in the shocking twist of Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory and Stephen King’s It. Perhaps most interesting is that fact that science itself has been influenced by Mary’s thinking: the technology she envisioned became an inspiration for real innovations.

There are as many reasons for the novel’s perpetual success as there are readers, but the truth is that everyone who comes to Mary’s masterpiece now brings with them certain expectations.

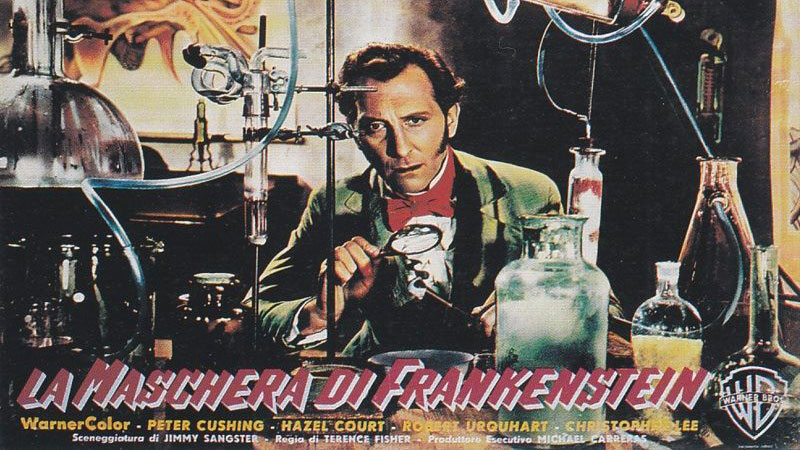

The image of Frankenstein’s Monster is burned into our cultural memory thanks to nearly two hundred years of adaptation for stage and screen and even in modern music: think of Metallica’s ‘Some Kind of Monster’ or Alice Cooper’s ‘Feed My Frankenstein’. The name has entered everyday use, and we all have our own idea of what it means.

In fact, it’s often surprising to encounter the novel for the first time and notice how it differs from the image we’ve inherited. The ‘monster’ isn’t green. There are no bolts through his neck. There are no hysterical screams of “It’s alive!” and, most importantly, Frankenstein is the name of the scientist and not his creation. Still, that the creature and his maker are identified with each other would have pleased Mary: it supports her argument that corrupt political systems make victims of the empowered and disempowered alike.

It’s the politics that are often overlooked by Shelley readers, mostly thanks to the Victorian habit of domesticating women’s writing and relegating Mary’s work to the status of ‘romance’. In many ways, though, the political element is what holds the rest together: questions of responsibility, control and the abuse of power remain at Frankenstein’s core.

Over the intervening years, it has continued to strike a chord in the wake of scientific as well as political progress – whether it’s the governing class or the scientist in the laboratory, in the end, Frankenstein explores the consequences of men playing God with the lives of others, and that theme never dies.

I found this very interesting, especially as I know very little about Mary Shelley's life. Looking forward to the next installment!